“`html

University of Michigan research illustrates how the extinction of dinosaurs reshaped Earth

Dinosaurs had such a profound effect on Earth that their unexpected extinction resulted in large-scale transformations in terrains—including the course of rivers—and these alterations are evident in the geological record, according to a University of Michigan investigation.

Researchers have long acknowledged the striking difference in rock structures from just prior to the extinction of dinosaurs to shortly after, but attributed it to sea level fluctuations, happenstance, or various abiotic factors. However, U-M paleontologist Luke Weaver demonstrates that when dinosaurs were eradicated, forests began to thrive. This significantly influenced rivers: The newly dense forests stabilized sediments and directed water into rivers with expansive meanders.

Weaver and his team analyzed sites across the western United States that displayed rapid geological transformations at the junction between the age of dinosaurs and that of mammals.

Through examination of these rock layers, Weaver and colleagues propose that dinosaurs were likely massive “ecosystem architects,” uprooting much of the existing flora and maintaining land between trees open and overgrown. The outcome was rivers flowing freely, without expansive meanders, across the terrain. With the extinction of dinosaurs, forests thrived, aiding in the stabilization of sediments and directing water into meandering rivers.

Their findings, published in the journal Communications Earth & Environment and funded by the National Science Foundation, showcase how swiftly the Earth can alter in response to catastrophic incidents.

“Often, when we consider how life has evolved over time and how environments have transformed, we usually think about climate change and its specific impact on life, or the formation of mountains and their effects on ecosystems,” said Weaver, assistant professor in the U-M Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences. “It’s infrequently considered that life itself could modify the climate and landscape. The direction of influence is not solely one way.”

The Chicxulub asteroid impact

Dinosaurs faced extinction after a massive asteroid struck the Yucatan Peninsula. Researchers searching for proof of the asteroid observed that the stratum covering the fallout debris was markedly dissimilar from the underlying rocks.

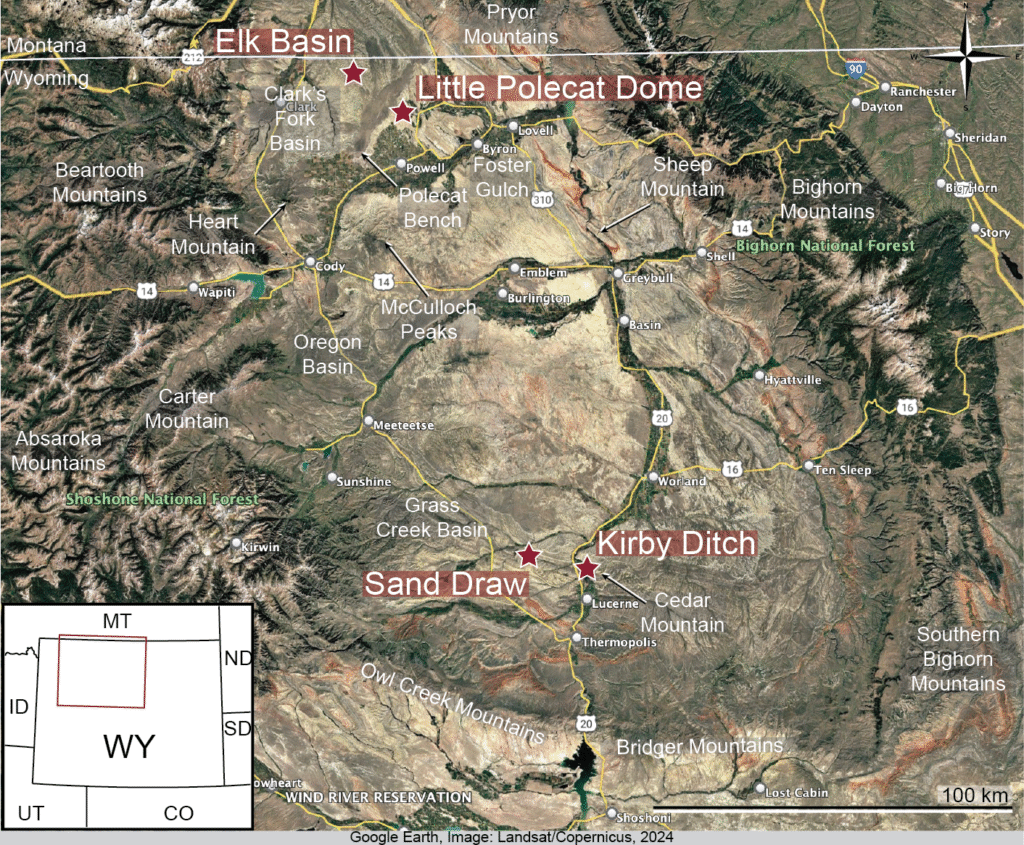

Weaver, along with his co-authors Tom Tobin from the University of Alabama and Courtney Sprain from the University of Florida, initiated their investigation into this abrupt geological alteration in the Williston Basin, an expanse covering eastern Montana and western North and South Dakota, as well as north-central Wyoming’s Bighorn Basin.

The early-career scientists’ curiosity in the geological enigma was sparked during fieldwork they conducted together as graduate students. While reviewing a prior study, the research group scrutinized a rock layer referred to as the Fort Union Formation.

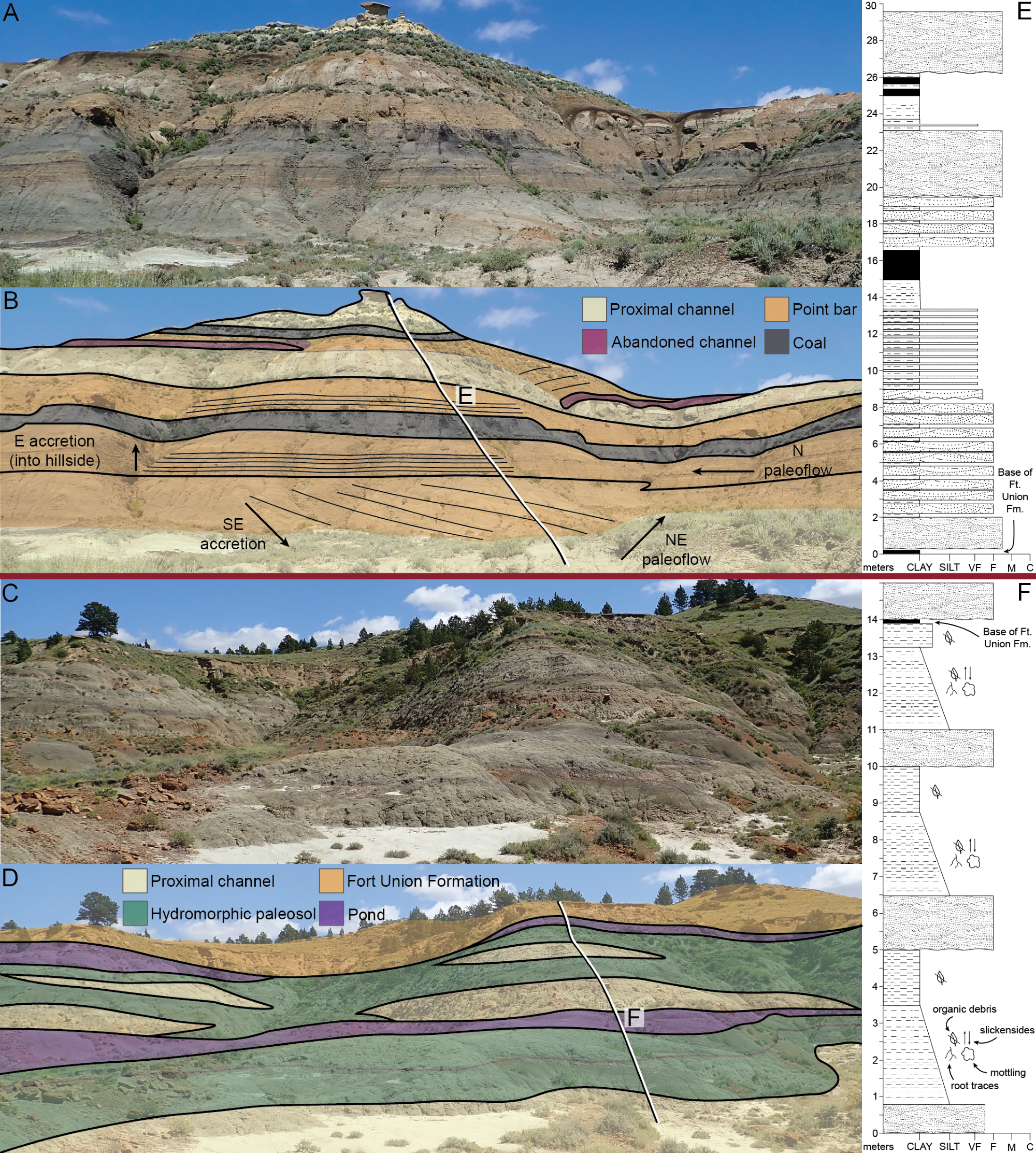

The Fort Union Formation was laid down following the extinction of dinosaurs and appears to consist of stacks of differently colored rocks—“pajama-striped looking beds,” as Weaver described. These vividly colored rock layers were believed to be pond deposits thought by some researchers to have formed during a period of rising sea levels.

The rock formation sharply contrasted with the layers beneath, which featured waterlogged, poorly developed soils reminiscent of those seen at the periphery of a floodplain. The researchers began to suspect that the geological shift was somehow associated with the mass extinction of dinosaurs, known as the Cretaceous-Paleogene, or K-Pg, mass extinction. Additionally, they began exploring the types of environments represented by these varying rock formations.

“What we discovered was that the pajama stripes were not pond deposits at all. They are point bar deposits, or those that form on the inner side of a large river meander,” said Weaver, who also serves as assistant curator of fossil mammals at the U-M Museum of Paleontology. “So rather than observing a still water, tranquil setting, what we’re genuinely looking at is a dynamic inside of a meander.”

“““html

The substantial river deposits were flanked by strata primarily consisting of lignite, a lower-quality variation of coal created from carbonized plant material. Weaver and his associates posited that these developed due to the stabilizing influence of dense woodlands, leading to less frequent river flooding.

“By stabilizing rivers, you restrict the influx of clay, silt, and sand to the distant areas of the floodplain, resulting in the accumulation of mainly organic matter,” Weaver explained.

The critical evidence to determine if the alteration occurred right after the K-Pg mass extinction? A delicate layer of sediment rich in iridium, an element typically delivered to Earth via cosmic phenomena. Nevertheless, the asteroid impact brought this element with it, which dispersed across much of the planet in a thin layer. This sediment layer rich in iridium, marking the K-Pg boundary, contains approximately three orders of magnitude more iridium than ordinary sediments, and is referred to as the iridium anomaly.

The research group subsequently concentrated on an area in the Bighorn Basin where the K-Pg boundary was yet to be identified. Investigating locations of geological transition between the dinosaur-bearing formations and those with Paleocene mammals, Weaver collected samples from a narrow band of red clay about a centimeter in width.

“To our amazement, the iridium anomaly was precisely at the interface between those two formations, right where the geology shifts,” he remarked. “This finding assured us that this isn’t merely an occurrence in the Williston Basin. It’s likely valid throughout the Western Interior of North America.”

The landscape before history

Nevertheless, the enigma regarding why the geological features of regions changed so significantly before and after the extinction of the dinosaurs persisted. Then Weaver stumbled upon a series of discussions surrounding how contemporary creatures like elephants shape their surrounding ecosystems.

“That was the illuminating moment when everything clicked into place,” Weaver stated. “Dinosaurs are enormous. They must have exerted some influence over this vegetation.”

Integrating previous research and the contributions of co-author Mónica Carvalho, assistant curator at the U-M Museum of Paleontology and assistant professor of earth and environmental science, who investigates changes in vegetation across the K-Pg boundary, Weaver and the research team proposed that the abrupt extinction of dinosaurs permitted forests to thrive, aiding in sediment retention, the formation of point bars, and the structuring of rivers.

“For me, the most thrilling aspect of our findings is the indication that dinosaurs may have had a direct effect on their ecosystems,” remarked U-F’s Courtney Sprain. “Specifically, the implications of their extinction may not only be evident through the absence of their fossils in the geological record, but also via transformations in the sediments themselves.”

Weaver believes the K-Pg extinction event serves as a cautionary tale regarding how Earth’s record may transform in response to human-induced climate alterations and biodiversity decline.

“The K-Pg boundary marked essentially a geologically instantaneous shift in life on Earth, and the modifications we are enacting to our biota and environments will likely appear equally as geologically instantaneous,” Weaver noted. “What is unfolding in our lifetimes is merely a blink in geologic timescales, thus the K-Pg boundary serves as our most relevant parallel to the swift reconfiguration of biodiversity, landscapes, and climate.”

“`