“`html

Globally, natural history museums possess approximately 3 billion specimens of flora and fauna—and these collections may also encompass insights essential for averting, preparing, and reacting to impending pandemics.

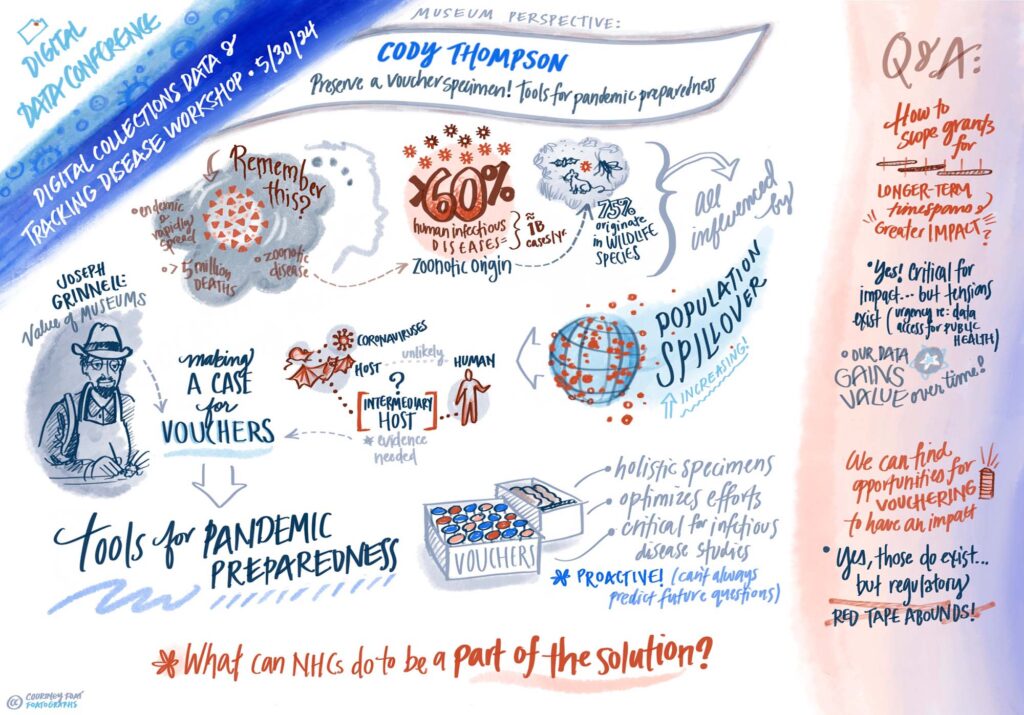

However, these collections remain an underutilized asset in formulating tactics to forecast or respond to disease outbreaks that could escalate into pandemics, as stated by a team of collection specialists and other authorities, co-directed by Cody Thompson, the mammal collection supervisor and associate research scientist at the University of Michigan Museum of Zoology and Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology.

In 2024, the researchers convened to evaluate how to harness natural history collections and integrate research across various fields to assist the world in preparing for potential future pandemics—an outcome that experts suggest is probable due to climate change and human encroachment into wildlife habitats. Their results were recently published in the journal BioScience.

“Museum collections effectively serve as a time capsule. For instance, our specimens at the University of Michigan span back a few hundred years. In regions like Europe, collections extend back significantly further,” remarked Thompson. “Given how we have cultivated natural history collections, preserved specimens, and documented information over time, museums present an invaluable resource for enhancing our forecasts of possible zoonotic pathogen (outbreaks) and their potential occurrences. This applies to both current and modern collecting.”

Insights from previous pandemics

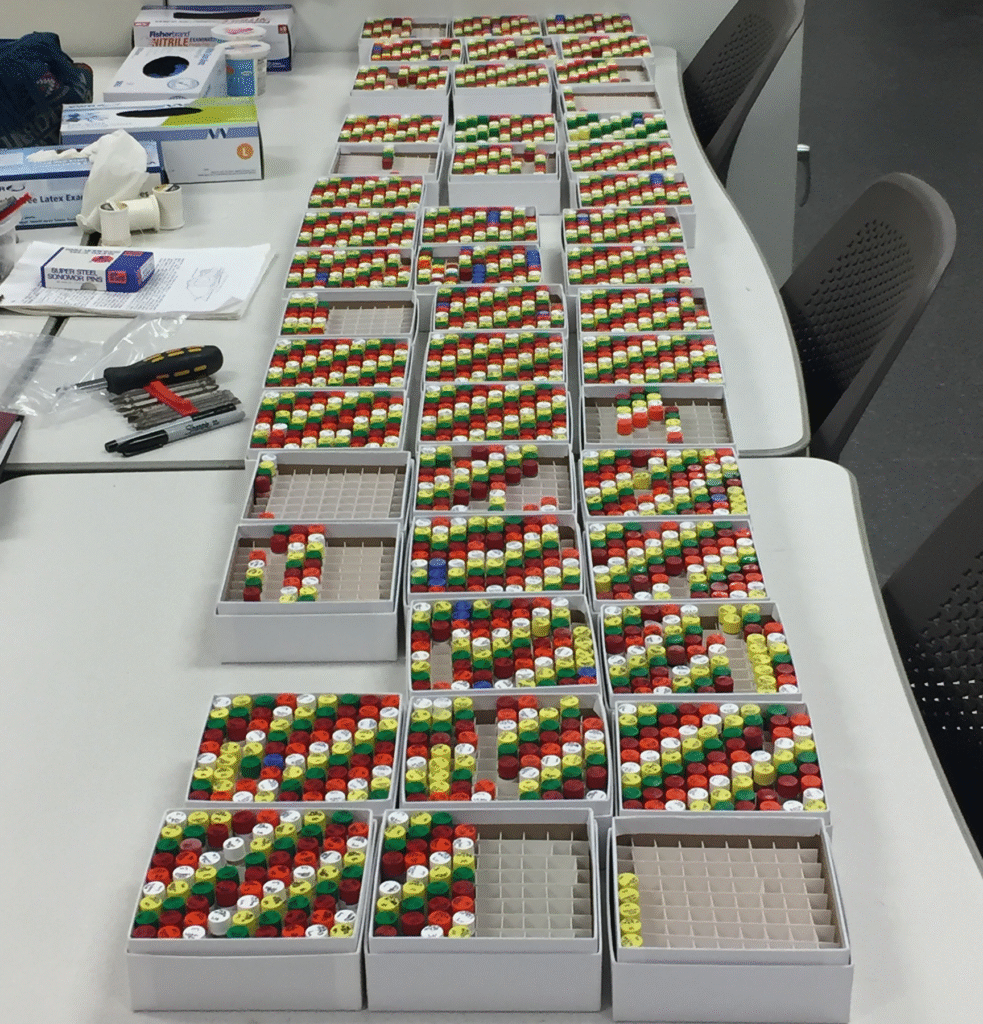

The initiative, supported by a National Science Foundation grant, stemmed from two workshops where collections experts and researchers evaluated insights gleaned from the COVID-19 pandemic and earlier pandemics, developing strategies on how collections can be more effectively included in upcoming pandemic responses. Co-authors from U-M include Nicte Ordonez-Garza, the biorepository collection manager at the U-M Museum of Zoology, and Oliver Keller, a collection specialist for the biorepository.

Participants comprised professionals in museum collections, One Health (an integrated approach addressing environmental, human, and animal health), pathobiology, bioinformatics, education, and computer science. The sessions featured professional facilitators who are also artists, creating graphical representations of the discussions on the spot, aiding in visually conveying the themes to foster further dialogue.

“Throughout the recent pandemic we faced, valuable lessons were learned,” stated Deborah Paul, lead author of the study and a biodiversity informatics expert and community liaison at the Prairie Research Institute. “We recognize that collections can provide crucial insight into natural phenomena—accounting for human integration within nature. Thus, this project’s objective was to assemble individuals possessing expertise in this area of research who actively explored the ongoing situations.”

Repository of knowledge

Globally, natural history collections—such as the U-M Museum of Zoology and Herbarium—are home to roughly “3 billion specimens that document life on our planet,” the researchers asserted. “These samples contain vital information that can be utilized in pandemic readiness, providing insights into the geographic distribution of pathogens and their hosts, the origins and transmission of disease, and the ecological factors inducing spillover.”

The authors emphasize the necessity for interdisciplinary collaboration and network establishment, enhancing awareness of natural history data across various fields, and advocating for financial support regarding workforce development, collection infrastructure, fieldwork, and digitization. Data must be searchable across domains, accessible, interoperable, and reusable to achieve significant impact.

“With the increasing volume of collection data, there’s a demand to interlink it and render it discoverable to disease biologists, virologists, and wildlife biologists here at INHS. We must establish connections between these data and the public health sector,” Paul remarked. “This requires investment in local infrastructure,

“““html

it signifies investing in local data management, it signifies investing in local proficiency.”

Moreover, interdisciplinary teamwork extends beyond just data sharing. For instance, specimens collected by field researchers must be stored by collections supervisors employing techniques that maintain the necessary information, such as RNA, required by pathobiologists, who utilize these resources to investigate and monitor disease-causing pathogens.

One planet, one health

The researchers evaluated pandemic preparedness and the contribution of collections within the framework of One Health. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention emphasizes that human health is intertwined with the health of animals, plants, and the environment, along with their interactions.

Shifts in global populations and their habitats, variations in climate and land utilization, and the rise in global transport have influenced the transmission of diseases between humans and animals—and amplified the necessity to not solely focus on human health and illness.

Paul stated that adopting a One Health framework enables earlier detection of illness outbreaks, swift communication with communities worldwide, and quicker reactions to threats. This approach preserves lives and protects the global economy from severe repercussions. As pathogens do not recognize geopolitical borders, it benefits all nations to jointly invest in the infrastructure and networks required to prepare for and confront any possible pandemic, she added.

“One of our key discoveries is that we must improve our efforts to make the information we gather on a regular basis available to those actively monitoring public health for diseases not only in the U.S. but globally,” Thompson remarked.

“`