During World War II, Britain was battling for its existence against German aerial attacks. Interestingly, Britain was simultaneously importing dyes from Germany. This is quite perplexing, to say the least. How can two nations engaged in conflict also be exchanging commodities?

There are numerous instances of this occurring. In fact, Britain traded with its adversaries for the majority of World War I. India and Pakistan engaged in trade with one another throughout the First Kashmir War, from 1947 to 1949, and again during the India-Pakistan War of 1965. Croatia and then-Yugoslavia also traded while in conflict in 1992.

“Nations indeed engage in commerce with their foes during wars,” states MIT political scientist Mariya Grinberg. “There is much variation regarding which items are traded, in which conflicts, and how long such exchanges persist during hostilities. But it does occur.”

As Grinberg has discovered, leaders often assess whether trade can provide them an upper hand by enhancing their own economies while not furnishing their adversaries with anything particularly beneficial in the short term.

“At its core, trade during wartime revolves around the balance between military advantages and economic repercussions,” Grinberg explains. “Halting trade prevents the enemy from accessing your resources that could enhance their military strength, yet it also carries a cost for you due to the loss of commerce and allows neutral nations to potentially encroach on your long-term market share.” Consequently, many nations opt to trade with their wartime opponents.

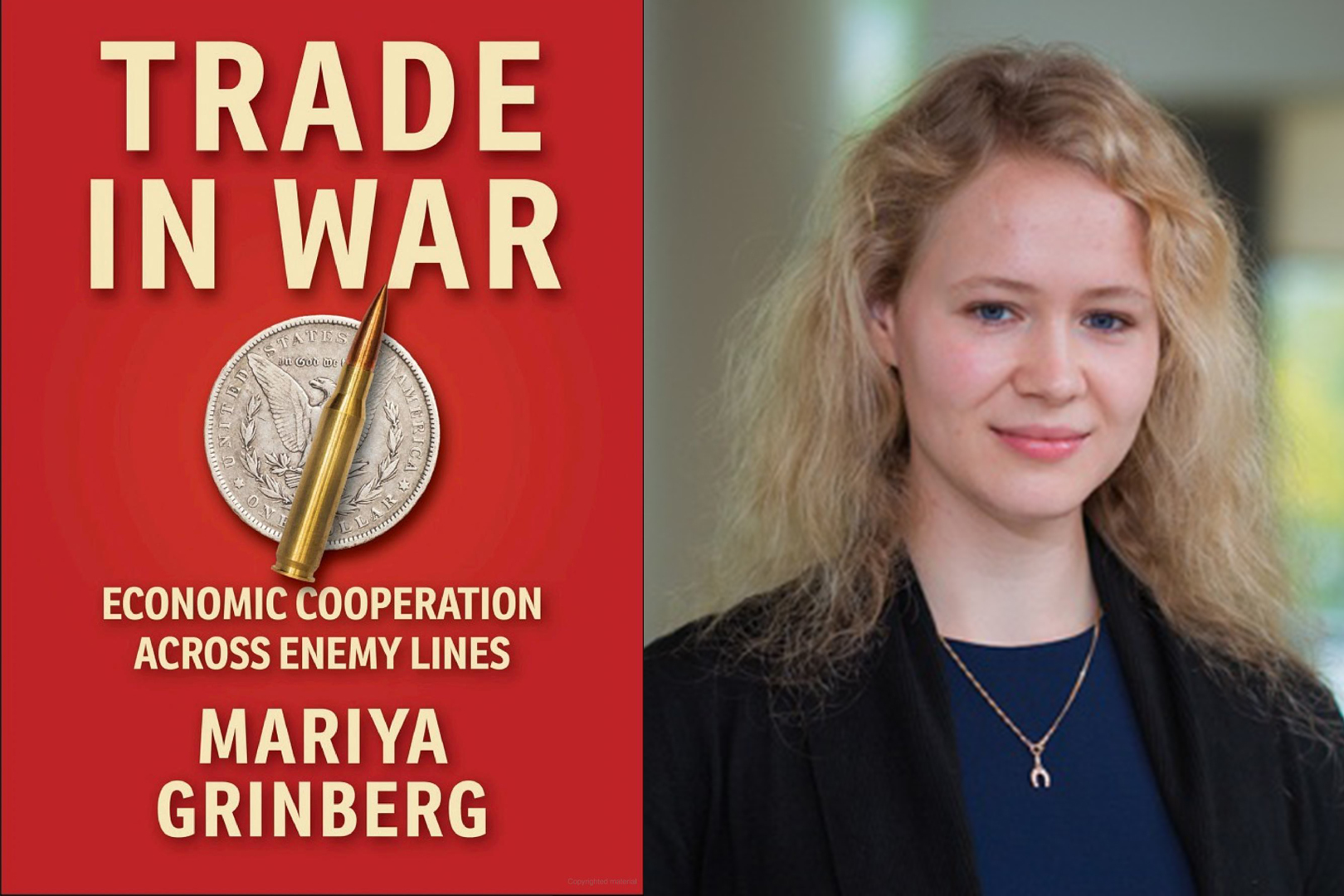

Grinberg delves into this subject in a pioneering new book, the first of its kind, “Trade in War: Economic Cooperation Across Enemy Lines,” which is published this month by Cornell University Press. This is also Grinberg’s debut book, as she serves as an assistant professor of political science at MIT.

Evaluating time and usefulness

“Trade in War” stems from research Grinberg initiated as a doctoral candidate at the University of Chicago, where she noted that the phenomenon of wartime trade had not been integrated into theories of state behavior.

Grinberg sought to explore this topic in depth and cleverly remarked, “I did what academics typically do: I reached out to historians and asked, ‘Historians, what insights do you have for me?’”

The concept of modern wartime trade began during the Crimean War, which saw Russia against France, Britain, the Ottoman Empire, and other allies. Prior to the conflict’s onset in 1854, France had purchased numerous Russian commodities that could not be transported due to delayed thawing of the Baltic Sea. To salvage its produce, France then convinced Britain and Russia to acknowledge “neutral rights,” established in the 1856 Declaration of Paris, which formalized the notion that goods in wartime could be shipped through neutral parties (sometimes serving as intermediaries for belligerent nations).

“This common perception, that we don’t trade with our enemies during war, is actually a remnant from a time when no neutral rights existed,” Grinberg points out. “Once neutral rights were established, all bets were off, leading to the emergence of wartime trade.”

Overall, Grinberg’s thorough examination of wartime trade suggests that it must be understood in relation to specific goods. During conflicts, nations measure the economic harm of ceasing trade of certain items; the practicality of particular products for enemies during war, and in what timeframe; as well as the expected duration of the conflict.

“There are two scenarios where wartime trade can occur,” Grinberg explains. “Trade is allowed when it does not aid the enemy in winning the war and when stopping it would jeopardize the state’s long-term economic stability, extending beyond the ongoing conflict.”

As a result, a state might export diamonds, understanding that an adversary would need to resell such items over time to fund any military efforts. Conversely, nations will refrain from trading products that can be swiftly converted into military applications.

“The balance is not uniform across all goods,” Grinberg notes. “Every product can potentially be transformed into something of military value, but the time required for this varies. If I anticipate a brief conflict, items that take longer for my opponent to adapt into military capabilities won’t help them win the current war, thus making them safer for trade.” Moreover, she emphasizes, “States generally prioritize sustaining their long-term economic stability unless the stakes are extraordinarily high.”

This examination elucidates some seemingly illogical wartime trade choices. In 1917, three years into World War I, Germany began supplying dyes to Britain. Notably, dyes possess military applications, such as being used as coatings for equipment. World War I, notoriously, extended far longer than early expectations. Nevertheless, by 1917, German strategists believed that the initiation of unrestricted submarine warfare would result in a swift victory, so they approved the dye shipments. This assessment proved incorrect, yet it aligns with the framework Grinberg has established.

Nations: Often inaccurate about war durations

“Trade in War” has garnered acclaim from other academics in the field. Michael Mastanduno of Dartmouth College remarked that the book “is a remarkable contribution to our understanding of how nations navigate trade-offs between economics and security in foreign policy.”

Grinberg herself acknowledges that her research carries multiple implications for international relations, one of which is that trade connections do not preclude conflicts, as some have theorized.

“We cannot assume that even robust trade relationships will prevent a confrontation,” Grinberg asserts. “Conversely, when we discover that our assumptions about the world may not be entirely accurate, we can seek alternative methods to deter warfare.”

Grinberg has also noted that nations are generally poor at predicting the duration of wars.

“States rarely accurately forecast how long a conflict will last,” Grinberg observes. This realization has laid the groundwork for a second ongoing project by Grinberg.

“Now I’m investigating why nations enter conflicts unprepared and why they believe their wars will conclude quickly,” Grinberg adds. “If individuals simply studied history, they would realize that nearly all of recorded history contradicts this presumption.”

Meanwhile, Grinberg believes there is a great deal more that scholars could uncover specifically regarding trade and economic interactions among warring nations — and she hopes her book will encourage further exploration into this area.

“I’m nearly certain that I’ve merely begun to scratch the surface with this book,” she concludes.