“`html

Health

Why are females twice as likely to develop Alzheimer’s compared to males?

Andrzej Wojcicki/Getty Images

Researchers examining chromosomes, menopause

An overlooked aspect of the Alzheimer’s enigma has been garnering more scientific focus: the reason women are twice as likely as men to develop this condition.

One might be inclined to attribute this difference to the fact that women generally live longer. However, experts researching the disease argue that this alone doesn’t explain such a substantial gap, and they remain uncertain about what truly accounts for it.

While numerous elements could be involved, researchers are honing in on two where the biological distinctions between women and men are evident: chromosomes and menopause.

Women possess two X chromosomes, while men have one X and one Y. According to researchers, variations between genes located on the X and Y chromosomes may heighten women’s risk of developing Alzheimer’s.

Menopause, the phase when the production of hormones such as estrogen and progesterone diminishes, is another evident distinction between the genders. Although these hormones are primarily recognized for their roles in the reproductive system, estrogen also influences the brain, researchers note.

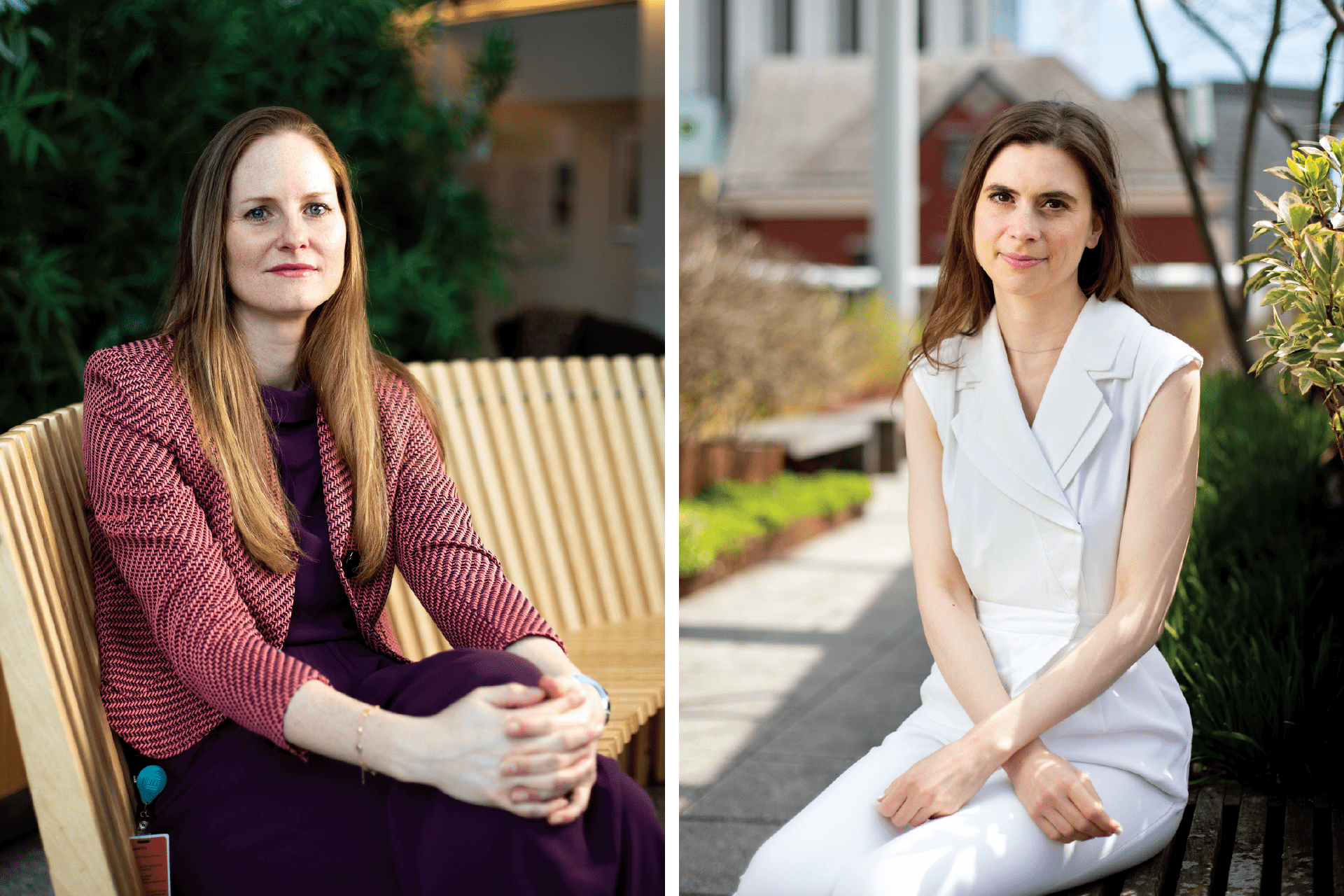

Researchers Rachel Buckley (left) and Anna Bonkhoff.

Photos by Veasey Conway/Harvard Staff Photographer

Whatever factors are involved likely tie into more complex neurological mechanisms, researchers suggest, highlighting similar sex-based variations in other ailments. For instance, multiple sclerosis and migraines are both more prevalent in women, while conditions like Parkinson’s disease, brain tumors, and epilepsy are more frequent in men. In certain instances—such as migraines in women and Parkinson’s in men—enhanced severity corresponds with increased occurrence.

“Epidemiologically, we observe that nearly all neurological disorders show variations in how many biological women and men are impacted,” stated Anna Bonkhoff, a resident and research fellow in neurology at Harvard Medical School and Mass General Brigham. “There’s a trend, for example, in MS and migraines for a higher incidence in females, while the opposite is true for brain tumors and Parkinson’s. Judging by these statistics, it’s clear that an underlying biological explanation must exist for these differences.”

The fundamental elements are genes, which are arranged on 46 chromosomes in humans, organized into 23 pairs. One of these pairs—XX in females and XY in males—holds the genes that determine sex-based traits, variations that are pivotal areas of study.

The X and Y chromosomes have significant differences, according to Bonkhoff.

The X chromosome is abundant in genes, while the Y chromosome has lost a considerable amount over time. Nevertheless, possessing two X chromosomes doesn’t imply that women experience a doubled exposure to the proteins and other gene products expressed by those genes, as one of the X chromosomes is silenced.

However, this silencing is not complete, Bonkhoff noted, allowing some genes on the silenced X chromosome to remain active. Research has indicated that genes found on the X chromosome are linked to the immune system, brain function, and Alzheimer’s disease.

“We recognize that biological males and females differ in the count of X chromosomes,” said Bonkhoff, the primary author of a recent review article in the journal Science Advances that explored sex-related distinctions in Alzheimer’s disease and stroke.

“Numerous genes associated with the immune system and the regulation of brain structure reside on the X chromosome, resulting in varying dosages between men and women. This seems to have an impact.”

“If we can discover methods to integrate sex differences for optimizing treatment for individuals, both men and women, that is the primary aim.”

Anna Bonkhoff

Another significant distinction between men and women pertains to their hormones. All humans possess three sex hormones: estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone. In females, estrogen and progesterone are prevalent, whereas testosterone predominates in males. When examining hormonal changes across genders with respect to aging, menopause marks a crucial turning point throughout a person’s life.

“Menopause contributes to the broader enigma, likely as one of the more significant factors,” Bonkhoff stated. “I’m not suggesting it’s the sole reason; aging alone is significant, and there’s substantial intriguing research evaluating the impact of aging on the immune system, which seems to influence cognitive changes.”

Women generally experience menopause between their mid-40s and mid-50s. During this phase, their ovaries cease the production of estrogen and progesterone, leading to the typical symptoms of menopause such as hot flashes, emotional shifts, cessation of menstruation, and sleep disturbances, among others.

In March, Rachel Buckley, an associate professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School, along with her team, pursued this hormonal line of inquiry in a study that explored the effects of hormone replacement therapy and the buildup of tau protein in the brain, a key feature of Alzheimer’s disease.

Buckley, who also serves as a neurology investigator at Massachusetts General Hospital, discovered that women who underwent hormone replacement therapy later in life, specifically after age 70, exhibited significantly elevated levels of tau accumulation and experienced greater cognitive decline.

The findings affirm what is known as the “timing” approach regarding hormone therapy, which posits that hormone replacement therapy can be safely utilized to alleviate menopausal symptoms but should not continue into advanced age.

This timing theory emerged in light of research conducted by the federally funded Women’s Health Initiative in the early 2000s, which revealed a correlation between hormone replacement therapy in women and accelerated cognitive decline. This was unexpected based on earlier study outcomes.

“““html

that suggested estrogen had safeguarding effects on cognition.

Subsequent studies, however, demonstrated that hormone therapy seemed to be protective in younger females but was linked to cognitive deterioration in women aged 65 and older.

Buckley’s investigation advanced that research, connecting it to physiological alterations in the brain. Alzheimer’s disease is characterized by the build-up of amyloid beta into distinct plaques in the brain — recognized as a significant hallmark of the disorder. These plaques initiate the formation of tangles of a protein known as tau, which then triggers harmful inflammation.

Buckley’s research indicated that hormone therapy among older women was correlated with an increase in tau and cognitive decline. It was not linked to a rise in amyloid beta, which is currently a prevalent therapeutic target.

“We’re working to establish a new study design where we can closely examine the timing of menopause.”

Rachel Buckley

The investigation, released in the journal Science Advances in March and partially funded by the National Institute on Aging, enabled Buckley, Gillian Coughlan, the lead author and neurology instructor, and their team to emphasize the role of hormone replacement in the accumulation of tau tangles in older women. However, Buckley noted that the study also underscores significant areas requiring further exploration.

The database utilized for the study lacked data on variables that may be crucial, such as a woman’s reproductive history, information on when the replacement therapy commenced, and the duration of hormone therapy usage.

Grasping the significance of that absent data, Buckley stated, is a step forward even though its absence restricts the conclusions that can be drawn in her study. To address this, Buckley is orchestrating her own research that will collect what she considers all the relevant information, including reproductive history and specifics of hormone therapy usage.

“We often work with a lot of existing secondary data, which is beneficial but comes with limitations regarding what we can achieve with it,” Buckley remarked. “We’re attempting to determine if we can establish a novel study design where we can truly analyze the timing of menopause, the changes occurring in the blood, the adjustments in the brain, the shifts in cognition, and how these factors might relate to risks in later life.”

Discerning how biological sex influences the risk of Alzheimer’s disease, Bonkhoff and Buckley indicated, can enhance our overall understanding of Alzheimer’s. They asserted that this insight holds the promise of uncovering new avenues for treatment and prevention of a disease that, despite years of research and encouraging recent advancements, remains poorly comprehended.

“It’s a vital goal in medicine to comprehend and then innovate ways to prevent or treat,” Bonkhoff stated. “If we can discover methods to integrate sex differences to refine treatment for individuals, both men and women, that is the ultimate aim.”

“`