Arts & Culture

Why are numerous novels situated at Harvard?

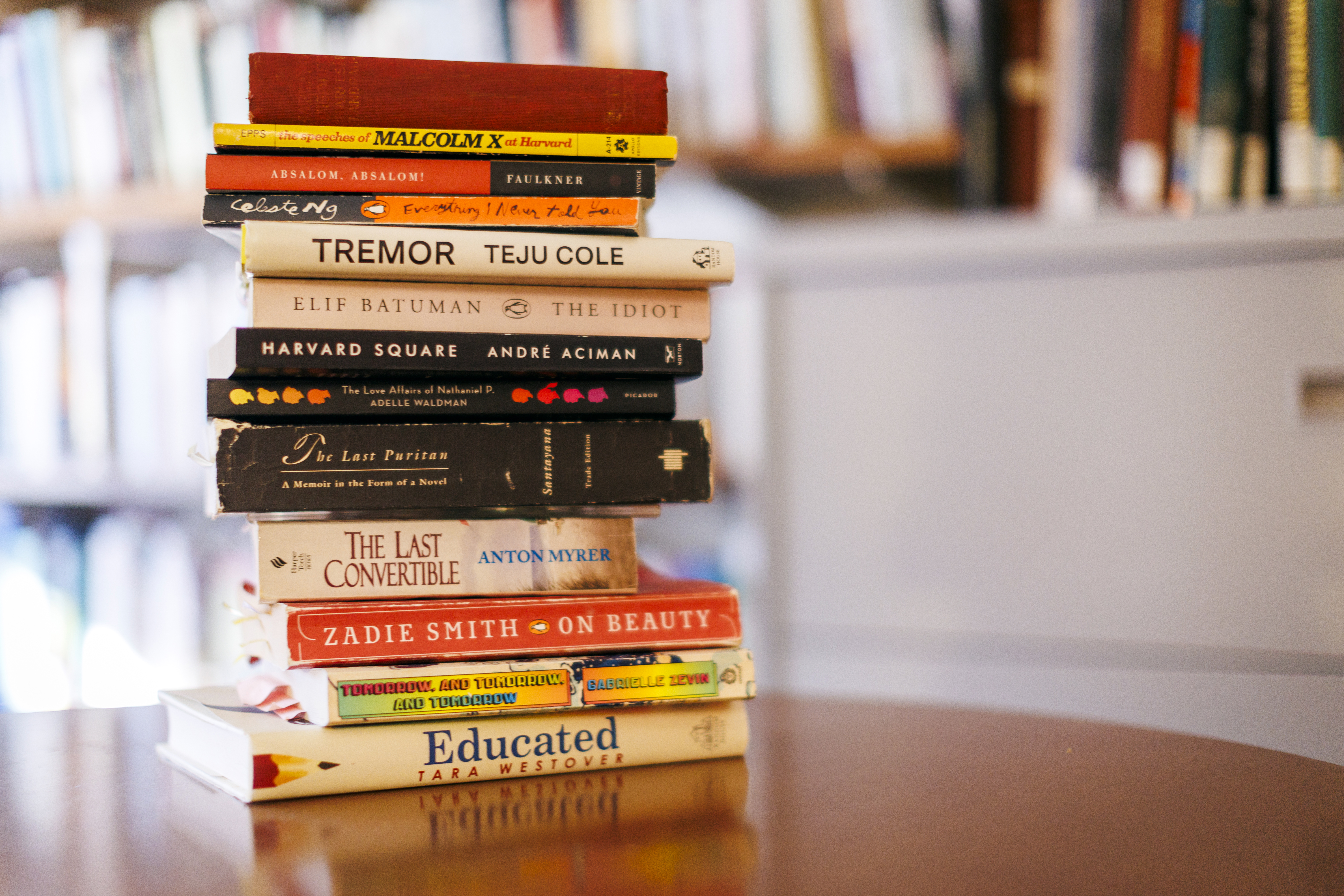

Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Beth Blum observes that the campus is a stunning, romantic locale perfect for exploring the clash between ideals and reality

In Gabrielle Zevin’s 2022 novel “Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow,” Sam Masur presents a business idea to his companion Sadie at the Harvard Museum of Natural History. On the other hand, “Everything I Never Told You” (2014) by Celeste Ng uses the River Houses adjacent to the John Weeks Footbridge to depict a romance involving a graduate student. Additionally, Selin Karadağ from “The Idiot” (2017) by Elif Batuman encounters her senior crush, Ivan, on the steps of the Widener Library.

The Harvard campus has historically been a backdrop for literary works penned by both alumni and numerous others.

Beth Blum, Harris K. Weston Associate Professor of the Humanities, offers a course through the English Department that delves into literature, films, television series, and even comics that engage with Harvard as a subject of cultural fascination and analysis. During the course, students explore notions of belonging, tradition, privilege, and rivalry, investigate authors’ backgrounds in the Archives, and even try their hands at crafting their own Harvard-related stories.

In this edited dialogue with the Gazette, Blum elaborates on the enduring allure of this genre, for writers and readers alike.

What qualifies as a “Harvard Novel”? How would you characterize the genre?

I perceive the Harvard novel as a branch of campus fiction, which refers to any narrative set on a university campus—an iconic example might be “Lucky Jim” by Kingsley Amis from 1954. Such works commonly focus on the struggles of a professor contending with a ruthless administration, dealing with personal dilemmas and interpersonal issues, or they portray a student’s perspective as they navigate this new realm and adapt to the intense microcosm of university life.

Certain tales are specifically about Harvard and distinctly located within the Yard, like Erich Segal’s 1970 bestseller “Love Story.” Meanwhile, Zadie Smith’s “On Beauty,” written during her time at Radcliffe, takes place at the fictional “Wellington College,” a setting that shares qualities with Harvard while combining elements of an imagined New England liberal arts college. Occasionally, Harvard merely forms part of a character’s developmental background, as observed in “Everything I Never Told You” or “Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow.”

What prevalent themes do you observe in these novels?

A key point that often emerges is that attending Harvard frequently involves family dynamics. It intertwines with parental aspirations and sacrifices, as well as with sibling relationships, a concept examined in “Everything I Never Told You.”

Another significant theme is the relationships between students and faculty, alongside the experience of pedagogical projection or transference. In [the 1973 film] “The Paper Chase,” the main character, Hart, becomes increasingly fixated on satisfying his overbearing law instructor, only to discover at the conclusion that the professor scarcely recognizes him.

The trope of the “street-smart outsider underdog” against the “privileged Harvard insider” is yet another recurring element. This relates to the dichotomy between creative idealism and institutional conformity.

Harvard novels often evolve into a type of morality tale, wherein the protagonist embraces their intrinsic values over those dictated by the competitive academic environment.

Belonging emerges as another immensely prevalent theme. The importance of community, and the fascinating individuals one encounters here, serve as a central point in this literature.

What do you believe accounts for the enduring appeal of Harvard’s campus?

As my students have observed, the University itself stands as a symbol of beauty and historical significance. However, that romantic narrative can contrast sharply with the stark realities of everyday life, and the finest Harvard stories highlight this juxtaposition.

“As my students have pointed out, the University is itself an object of beauty and history. But that romantic history can feel incongruous with the gritty realities of daily living, and the best Harvard stories bring this to the fore.”

For example, the protagonist Selin in “The Idiot” describes the University handyman having to navigate the decorative antlers suspended from the dining hall ceiling while trying to avoid being harmed by them. This tension between perceiving Harvard spaces as romantic historical artifacts, as anticipated by incoming students, and the pragmatic necessity of maintaining these spaces—with all the labor such upkeep demands—can yield poignant opportunities for modern fiction.

A common strategy is to exploit the University’s time compression into this four-year frame to facilitate dramatic opportunities. For students, there is a finite period within which to maximize their academic experiences and relationships, thus creating a heightened sense of stakes that fosters suspense and narrative momentum.

Do you believe these books resonate differently for Harvard students compared to external readers?

In my course, we have discovered that the experience of engaging with these texts can markedly differ for a Harvard affiliate compared to a reader who is not familiar with the Harvard context. Our findings also indicate that the reading experience varies significantly between students and faculty.

For students, one of the most pivotal and consistently intriguing aspects of Harvard discussed in class revolves around the housing system, the distinctive traits and identities of the various Houses, and the complex dynamics surrounding House and roommate selections — a sort of updatingof the medieval “wheel of fortune,” the randomness of destiny.

For a faculty member like myself, the Houses play a significantly less prominent role in my everyday interaction with the University. Engaging with these texts provides me with perspectives on the commonplace elements of my students’ experiences.

What advantages do current students gain from exploring these texts?

A potential drawback of the course is that campus traditions may begin to appear somewhat absurd, resembling a personal campus parody. However, I believe this is actually a beneficial outcome, as it fosters a touch of irony and a sense of distance from institutional demands.

More importantly, the course enables students to engage with campus life and the educational process from a fresh perspective. Iconic Harvard sites that we encounter daily are featured in the writings, ranging from W.E.B. Du Bois’s undergraduate texts regarding the Johnston Gate in his English 12 course, to the same Johnston Gate serving as “the wall” for disciplining rebels in Margaret Atwood’s “The Handmaid’s Tale.”

One of their projects requires them to discover a “Harvard story” within the University’s archives and then analyze how an author’s interactions with campus culture may have shaped their philosophies or artistic expressions. One student researched the classes documented on E.E. Cummings’ Harvard transcript and explored how this influenced the development of his modernist style. Another student investigated T.S. Eliot’s assessments of Harvard’s “elective system” of education and how these critiques correlate with his literary reviews.

On a more extensive scale, delving into these texts can assist students in placing themselves within a cultural lineage that they are actively influencing and defining, while also contemplating this institutional connection that will remain a significant aspect of their lives.

If someone is eager to explore a “Harvard novel,” what would you suggest as a starting point?

As a modernism scholar, I am inclined to recommend William Faulkner’s “Absalom, Absalom!” a modernist narrative published in 1936, relayed through the flashbacks of Quentin Compson to his Harvard roommate, Shreve.

However, I am currently reading “The Class” by Erich Segal. Similar to his earlier work “Love Story,” this novel is set at Harvard but chronicles the journeys of five distinct students; it begins at their 25th class reunion and then flashes back to their freshman years. This dual timeline serves as both a reflection on the uniqueness of the student experience and a testament to how influential that experience became in the lives of the characters.

I certainly intend to include it in future iterations of the course. I eagerly anticipate the insights the students will draw from it.