“`html

Arts & Culture

When refuse transforms into a cosmos

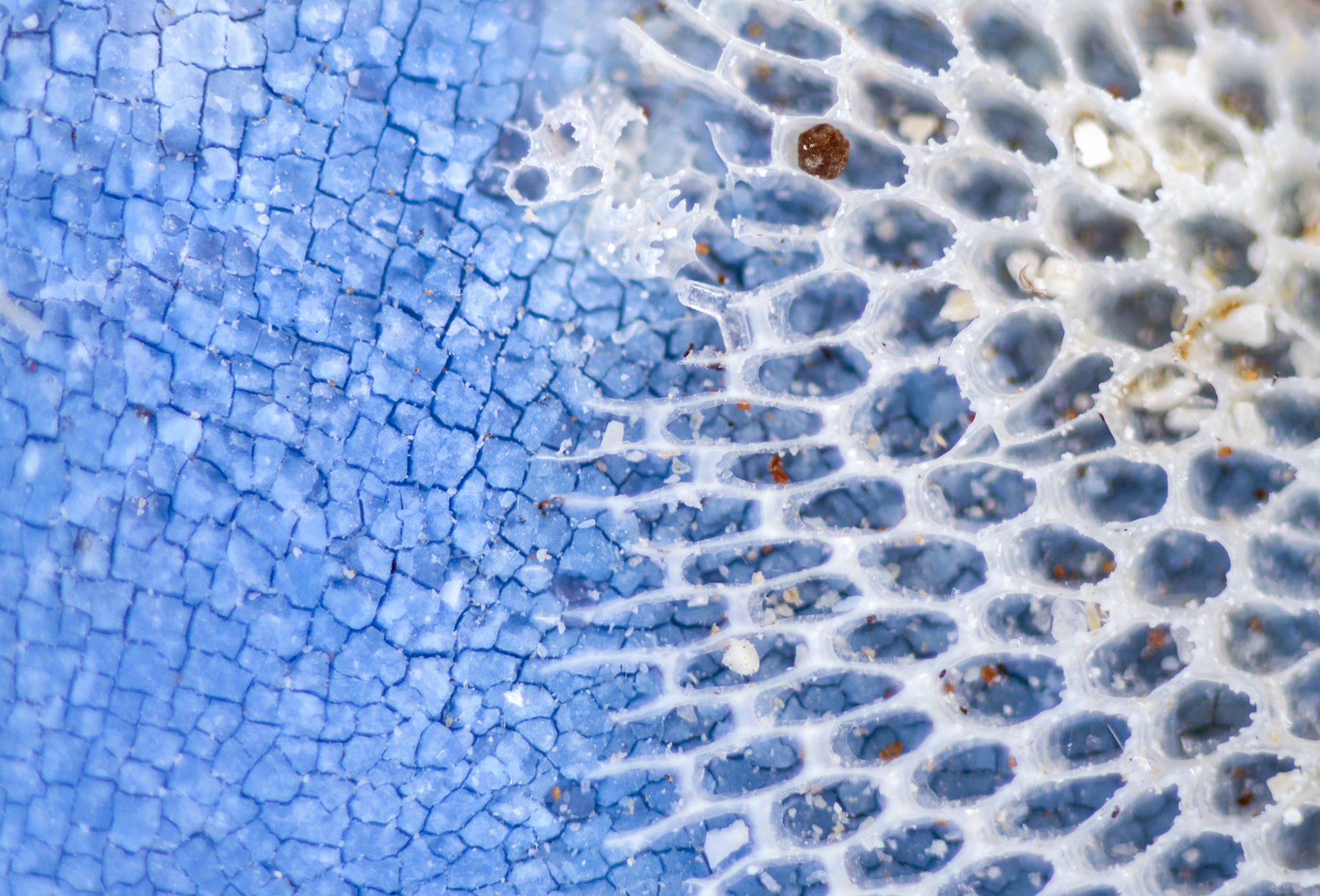

Bottle caps discovered on the Australian shore.

© TRES [ilana boltvinik + rodrigo viñas], image illustration by Liz Zonarich/Harvard staff

Art collective unveils ‘intraterrestrial’ realms at Harvard Peabody Museum

The bottle caps that washed ashore in Australia appeared akin to tiny planets. Some resembled flat, hard spheres composed of marble; others appeared fluid and strikingly reminiscent of Earth. Each had been inhabited and altered by aquatic invertebrates known as bryozoans.

The unusual marine debris captured the interest of the art collective TRES and became the foundation of their exhibition, “Castaway: The Afterlife of Plastic,” currently showcased at the Harvard Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnography. During a 2½-month road excursion in a Toyota camper van, the Mexico City-based pair, ilana boltvinik and rodrigo viñas — who choose not to capitalize their names — documented the bottle caps in addition to soda cans, pieces of leather shoes, doll fragments, deodorant bottles, and rubber gloves collected along the Australian coastline.

“Even our waste has turned into a stage for other forms of life.”

– ilana boltvinik

TRES is no stranger to discovering elegance in what many might disregard: Their previous endeavors have showcased discarded chewing gum scraped from the streets of Mexico City, cigarette remnants, and even recovered bottles filled with urine. “A primary focus for us is to present an alternative viewpoint on waste,” viñas stated. “We aim to suggest a more intimate connection with our refuse.”

The motivation behind “Castaway” emerged during a past initiative, “Ubiquitous Trash,” which compiled and explored refuse gathered in Hong Kong. They encountered bottle caps adorned with the image of the Hong Kong actor and gourmet chef Nicholas Tse, although that specific type of bottle was only accessible in mainland China, boltvinik explained.

“One of the inquiries we had initially, as we enjoy tracing the origins of items, was, ‘Alright, this is the bottle cap, where’s the rest of the bottle?’ They are likely submerged at the ocean’s depths. This led us to consider bottle caps as the tips of icebergs, a mere fragment of a much larger narrative.”

Calcium formations are evident in this bottle cap from “From the Future to the Present.”

© TRES [ilana boltvinik + rodrigo viñas]

The duo anticipated discovering beautiful bottle caps on their journey through Australia, yet they were astonished by the peculiar, coral-like material that had developed on and within them. This substance sometimes created perforations in the plastic or transformed its surface into entirely new shapes and textures that mimicked the surfaces of extraterrestrial worlds. They consulted Paul Taylor, an invertebrate paleontologist and bryozoologist at the Natural History Museum in London, who recognized the growths as the calcium deposits of jellyella eburnea, a species within the phylum Bryozoa.

Bryozoans are minuscule invertebrates that collaborate to form the intricate calcium-based structures that TRES encountered. These organisms are recognized for their division of labor among their colonies. Some filter the water; others focus on reproduction; and many construct their habitats.

“It’s an entirely different universe; it’s remarkable,” boltvinik remarked.

Trees at Yallingup Beach, Western Australia, resemble found rope in “Parallel Lives I.”

© TRES [ilana boltvinik + rodrigo viñas]

Found plastic rope mirrors a tree in Yallingup Beach, Western Australia, in “Parallel Lives II.”

© TRES [ilana boltvinik + rodrigo viñas]

The exhibition encourages attendees to dismantle the barriers

“““html

between organic and synthetic, treasured and worthless, virtuous and immoral. Ultimately, plastic has morph into new habitat realms for an “intraterrestrial” organism, as TRES described, and that organism has reshaped those habitats to resemble itself.

The exhibition is the outcome of the Robert Gardner Fellowship in Photography, a Peabody Museum initiative that provides funding for accomplished artists to produce and release a significant photographic project “on the human experience anywhere across the globe.” TRES was awarded the fellowship in 2016.

Ilisa Barbash, the visual anthropology curator at the Peabody Museum and the organizer of “Castaway,” mentioned that the pieces pose a question frequently addressed in her domain.

“In anthropology, the aesthetics often present a challenge, particularly when engaging with sensitive subjects — trauma or conflict or waste. What happens if the images are appealing?”

“Intraterrestial Aliens: Forgotten Smell.”

© TRES [ilana boltvinik + rodrigo viñas]

“Things in a Forgotten Map I.”

© TRES [ilana boltvinik + rodrigo viñas]

The exhibition also establishes links to Harvard’s scientific legacy. Alexander Agassiz, the offspring of Louis Agassiz, who initiated Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology, led explorations to Australia in the same vicinity that TRES studied. The Peabody Museum partnered with the Museum of Comparative Zoology’s Ernst Mayr Library to incorporate actual jellyella eburnea formations from Australia into the display.

“We cannot control everything,” boltvinik remarked. “Even our waste has transitioned into a substrate for different forms of life. It’s not that this was ever intended for such purposes, but the world extends beyond humanity, and occurrences in the world exceed human influence.”

“Castaway: The Afterlife of Plastic” is available for viewing until April 6 at the Harvard Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology.

“`