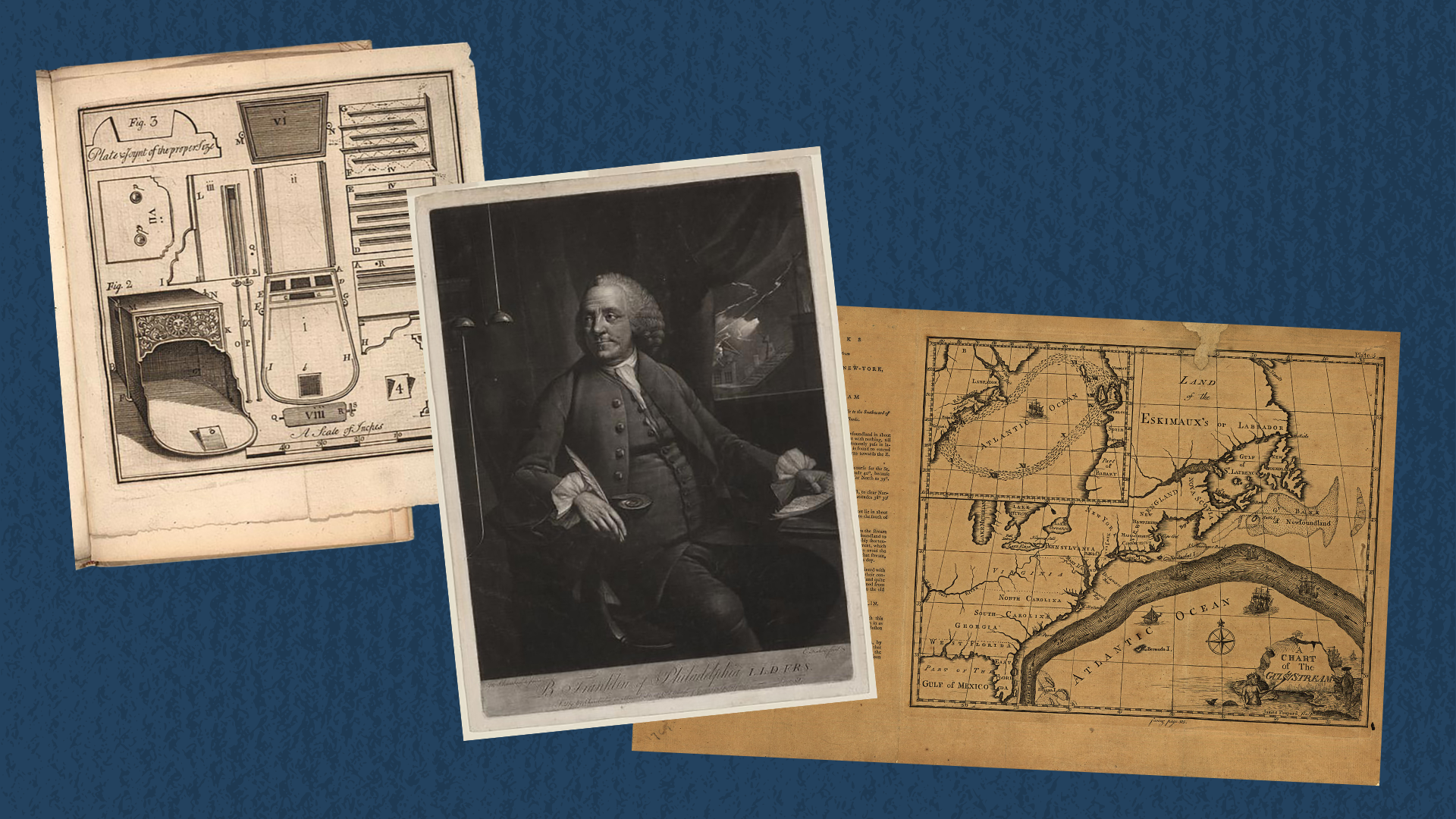

Historian Joyce Chaplin’s recent publication about Benjamin Franklin (center) delves into one of his lesser-celebrated innovations: a stove (left). The underlying science contributed to the comprehension of atmospheric phenomena such as the Gulf Stream (right), which Franklin was instrumental in mapping for the first instance.

Images sourced from the Library of Congress; illustration by Liz Zonarich/Harvard Staff

Science & Tech

When a stove’s merits extend beyond mere hot air

Science historian investigates how Benjamin Franklin’s creation ignited new perspectives on weather and technology

Joyce Chaplin believed she had concluded her studies on Benjamin Franklin.

“However, while I was perusing information about the Little Ice Age and the notably harsh winter of 1740 to 1741,” noted Chaplin, the James Duncan Phillips Professor of Early American History. “Significant harbors were reportedly freezing over — in Boston, London, and Venice. As a result, famine struck several regions, including Ireland, where it’s estimated that up to 20 percent of the populace may have perished — a toll greater than the more renowned Great Hunger of the 19th century.

“Throughout, I kept pondering, ‘I recognize those dates, 1740 and 1741, from somewhere.’”

Chaplin, a specialist in early American science, technology, and medicine, eventually connected the dots. These were the years when Franklin — a modest printer who evolved into a globally renowned scientist, inventor, and statesman — conceptualized the prototype for his Pennsylvania fireplace, a flat-pack of iron plates colonists could assemble and introduce into their hearths to enhance heating.

“It was developed in the midst of that exceedingly cold winter as a form of climate adaptation,” elucidated Chaplin, who has extensively documented Franklin’s scientific contributions. “The design aimed to consume less wood while providing greater warmth than a conventional fireplace.”

Franklin proceeded to create at least five distinct versions of this impactful technology over a span of fifty years, transitioning from wood to coal as fuel. Chaplin’s newly released “The Franklin Stove: An Unintended American Revolution” illustrates how this seemingly simple invention led to fresh insights regarding weather, technology, and comfort.

We engaged in a conversation with Chaplin, who is also a faculty member in the History of Science Department, to discuss the book and its many implications for the 21st century. The discussion was refined for brevity and clarity.

Joyce Chaplin.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

You released an intellectual biography of Benjamin Franklin in 2006 and curated an edition of his autobiography for Norton a few years after. What continually draws you to this 18th-century figure?

The common perception is “Poor Richard,” Franklin’s pseudonym from the almanacs he published. However, he is significantly more intricate than that. He was the youngest son of a Boston chandler, someone who crafted soap and candles from animal fat. It was a perfectly respectable but not particularly distinguished upbringing.

The conventional means of advancing for a man of Franklin’s background included warfare or some military profession to elevate his status. Politics, if feasible, was another option. Writing could also be a path. Science had started to integrate into popular culture, as figures like Isaac Newton and Robert Boyle became widely recognized following their monumental discoveries.

I believe Franklin surveyed all these possibilities. In the end, he looked at Newton and contemplated: “Why not pursue that path?”

Is it appropriate to categorize the Franklin stove as one of his less recognized inventions?

At present, I believe that’s an accurate assessment. Many are aware of Franklin’s invention of the lightning rod. Those who require progressive lenses usually recognize that he created bifocals. Others might be acquainted with his more whimsical inventions — his swimming fins, his folding chair/step stool for accessing books in the library. However, given the climate context surrounding this particular invention, perhaps the public will begin to appreciate the stove as pivotal to his scientific life.

Let’s explore the environmental challenges Franklin encountered during the winter of 1740 and ’41. It extended beyond the severe cold.

Franklin recognized that the increasing number of settlers and births across the area would lead to deforestation, making firewood more costly and potentially inaccessible for the impoverished. We possess his accounts of individuals pilfering firewood or tearing down parts of fences.

Yet, the most ambitious aspect of his initiative was to enhance people’s comfort like never before. The extremely harsh conditions made this an intriguing example of Enlightenment optimism — that humankind could harness science and technology to improve life, regardless of the circumstances.

“Atmosphere“`html

was a comparatively fresh term in regard to characterizing the envelope surrounding the Earth, and this is what Franklin believed a proficient heating system could generate indoors.”

How did the stove contribute to the enhancement of knowledge about the natural environment?

Atmosphere was a comparatively fresh term in relation to defining the envelope enveloping the Earth, and this is what Franklin perceived a well-designed heating system could produce in interior spaces. He detailed in a self-published brochure how his fireplace functioned based on the principle of convection: that air, when heated, will expand and ascend. What is desired is some kind of heat source that achieves this layer by layer until the complete room is heated.

However, Franklin also applied this principle to clarify atmospheric occurrences outside. He utilized it to illustrate how storm systems travel along the Atlantic coastline. Ultimately, he employed it to elucidate the Gulf Stream — describing how warm air rises from the Gulf of Mexico and disperses over the Atlantic Ocean correlated with the warmer water current beneath. When conveying these grand assertions, Franklin would frequently write something akin to: “Just as there’s a draft of air from your fireplace to the entrance.” It was a brilliant tactic for rendering science comprehensible to a literate audience.

Franklin is recognized for his later-life abolitionist sentiments, but your publication introduces yet another aspect of how he benefited from slavery before that. What new revelations did you discover?

I had learned from studying my colleague John Bezís-Selfa’s “Forging America” (2004) that there existed an iron industry in the colonies, including Pennsylvania. I also suspected from Bezís-Selfa’s accounts that enslaved Black individuals performed various tasks on these plantations.

I visited the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, which preserves most of the extant records of the Pennsylvania iron sector, and indeed discovered these two enslaved men — Cesar and Streaphon — who labored in the iron facility that produced a majority of the fireplaces in Pennsylvania.

One of these individuals — Streaphon — succeeded in purchasing his own emancipation. To me, this was a significant sign that the aspiration for freedom was ever-present. It is evident throughout early American history.

What motivated Franklin to attempt to reduce emissions from his stove?

He was horrified by the polluted air in cities like London. Consequently, he sought to design the last three iterations of his stove to recycle smoke — by redirecting the smoke that would typically flow up the chimney back into the fire.

Franklin rightly noted that smoke is fundamentally particles of unburned fuel. If it could be ignited again, at least it is more efficient. Less fuel is squandered, and less waste is released into the atmosphere. He was so dedicated to this goal that a friend humorously referred to him as “a universal smoke doctor.”

To me, it’s a fascinating comment on scrutinizing the level of emissions that already appeared to jeopardize human health. Naturally, what is identified decades after his demise in 1790 is that certain emissions are imperceptible. The American scientific observer and researcher Eunice Foote recorded the climate-altering impacts of CO2 in 1856.

You draw a connection between modern techno-optimism and Franklin along with other innovators from his time, who believed they could invent their way out of an environmental crisis. What insights does your book offer for those who inherit this mindset?

I do not believe Franklin intended to endorse coal burning in an industrial context, but he did endorse it as an energy source. This tells me: Avoid opting for the quick and apparent solution. At the very least, approach it with skepticism and observe its effects.

We should be cautious of the fantasy of a singular solution, believing we merely need to discover one method to sequester carbon from the atmosphere. Or that we can swiftly transition to sustainable energy without implementing climate mitigation before atmospheric chemical changes worsen.

We will require more than a solitary inventor, device, or hero. There are simply too many variables for one solution to be feasible. We must adjust our trajectory promptly with numerous solutions collaborating together.

“`