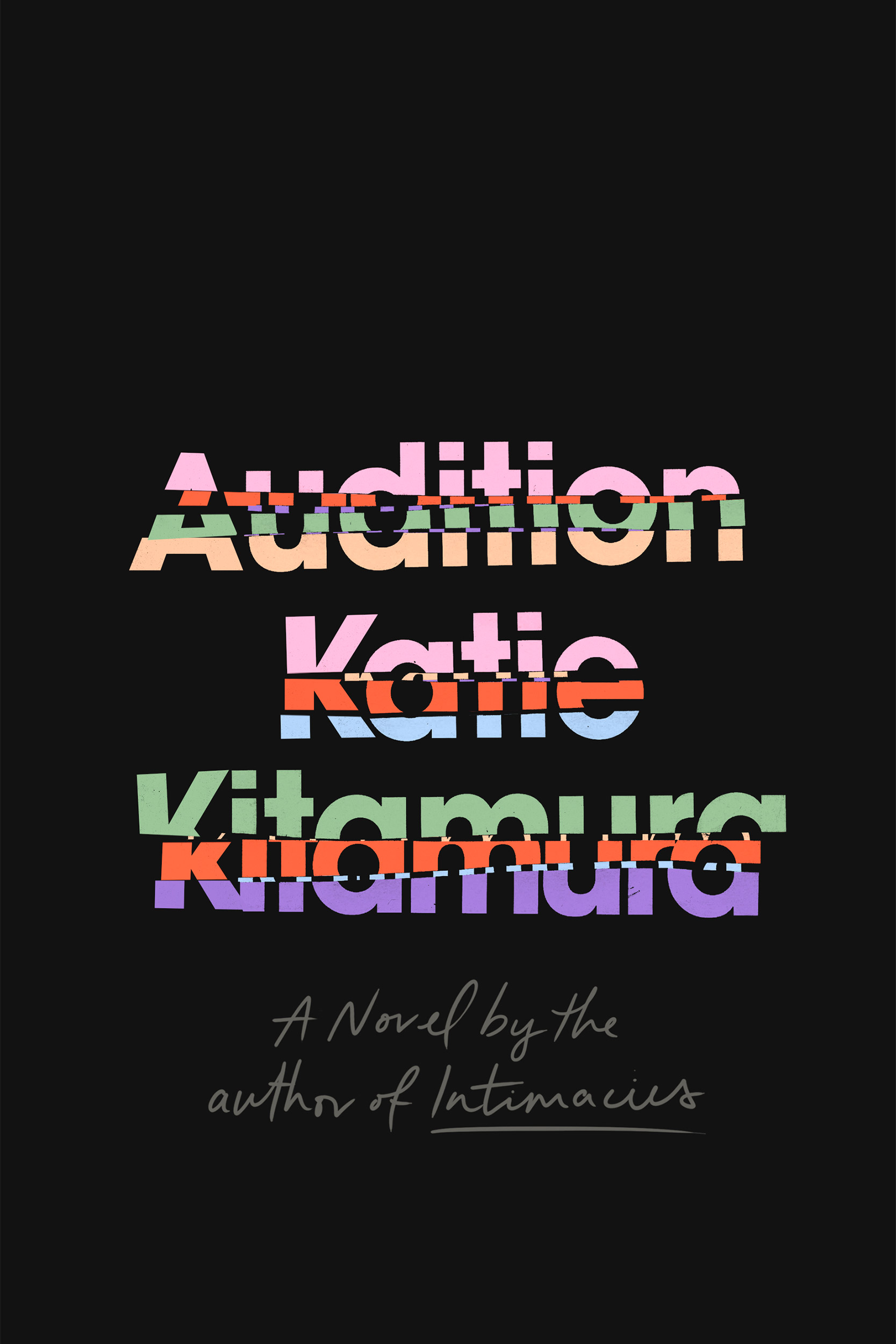

Image by Clayton Cubitt

Arts & Culture

What genuinely frightens Katie Kitamura

Before her Harvard appearance, the writer discusses performance, privacy, and the horror influences behind her new novel

On Tuesday, the Mahindra Humanities Center will welcome author Katie Kitamura, in dialogue with Claire Messud, the Joseph Y. Bae and Janice Lee Senior Lecturer on Fiction in Harvard’s English department.

Kitamura released her fifth novel, “Audition,” earlier this month. Similar to many of her previous works, including the praised “Intimacies” from 2021, it’s taut, compelling, and at times unsettling — this time exposing the peculiar nuances of midlife, both within and outside a family’s residence in New York City.

Recently, Kitamura was recognized as a 2025 Guggenheim Fellow in fiction. She resides in Brooklyn with her spouse, the novelist Hari Kunzru. The subsequent interview has been lightly modified.

This recent novel occurs in an atmosphere of uncertainty. In midlife, the protagonist may achieve great success or be on the verge of a collapse. She might be a mother, or perhaps not. She might be harboring secrets; her spouse could be doing the same. It’s disquieting — is there any possibility you’re morphing into a horror author?

I appreciate this inquiry. For my last three novels, I’ve always had a genre in mind while drafting them. I created a novel titled “A Separation,” which I regarded as a missing-persons narrative, a sort of mystery. Following that, I penned a book called “Intimacies,” which is set in a war crimes tribunal; I viewed that as a courtroom drama.

For this piece, when I began writing, I was intrigued by the idea of engaging with horror as a genre. The book that resonated with me was “Rosemary’s Baby,” authored by Ira Levin — another tale concerning troubled motherhood and New York real estate. These characters, this family: They’re confined within this apartment, and the tension escalates.

There are these eerie instances — is this truly my son? Is my husband everything he seems?

I believe the most terrifying moments in horror arise when you observe something you think you understand, only to find something bizarre. In Shirley Jackson’s “The Haunting of Hill House,” one character gazes out the window and perceives a part of the house she shouldn’t have visibility of. The entire geography and structure of that home has inexplicably altered.

I sought to evoke that sensation here: The main character is observing individuals she thinks she knows, and they appear as strangers to her. That feeling, to me, is very adjacent to horror.

“The main character is observing individuals she thinks she knows, and they appear as strangers to her. That feeling, to me, is very adjacent to horror.”

It has been noted that this novel possesses a pandemic resonance. Was that intentional on your behalf?

Well, there’s not a single mask, vaccine, or virus mentioned in the book. However, it was created during the pandemic, and it was only in the last few weeks that I truly comprehended how it embodies many aspects of a pandemic narrative: a compact apartment filled with family members, lacking sufficient space, which inevitably drives them to frustration on some level.

That was not my original intention. Nevertheless, my belief is that as a writer, one cannot avoid inhaling the atmosphere around them; all of it, everything in the sociopolitical climate, tends to reflect on the pages in some way.

The title is “Audition.” Your protagonist is an actress — keenly aware of others’ performances when offstage. And performance has been a recurring theme in your work — the fundamental fluidity of identity, and our interactions with one another.

Indeed. I think some may read my literature and interpret it as a critique of that — suggesting that I am highlighting those performances as inauthentic in some manner.

Yet, it’s almost the contrary: I believe we fundamentally learn our identities through performance. When I observe my children, they are discovering what it means to exist in the world, in part by emulating what they’ve observed around them. It’s inherently natural: to adopt different roles in various contexts.

As a novelist, I’m intrigued by those instances when the cracks between roles become evident, or when the façade begins to fade. For a fleeting moment, one might glimpse something unrefined or uncontrolled — and that can be alarming.

We might coexist with a spouse, child, or parent for many years — and never truly uncover certain facets of them. It raises the question of how well we can genuinely understand one another.

To me, a flourishing relationship is one that permits the other individual a certain level of privacy.

I perceive the idea of total transparency between two people as somewhat mythical, and I’m uncertain it’s particularly beneficial. There are aspects of myself that I prefer to keep to myself, which I don’t feel an overwhelming urge to share with my partner. Likewise, I contend that there are elements of him that he should retain for himself.

There’s a poignant quote by [Rainer Maria] Rilke about love: “All companionship can consist only in the strengthening of two neighboring solitudes” — the notion that love could be about sharing space while simultaneously valuing one’s independence.

Your novels often showcase a genuine admiration for language and performance, literature and visual art. Beyond your writing, you teach writing at New York University. During this era of AI and ecological dilemmas, why does this seem significant to you?

The day after the election, my students entered my workshop asking, “What’s the purpose of writing fiction in such times?” I responded that never has there been a moment when writing fiction felt more vital to me.

I convey to them that if books lacked power, why would they be facing censorship across the nation? If they posed no threat to authority, why would they consistently be targeted? Engaging with language thoughtfully and skillfully, as well as maintaining control over it, will be immensely important in the years to come.

One function of fiction is, certainly, to reflect reality as it exists and as we perceive it. However, it also serves to envision an alternative reality. And if we cannot conceive of a different kind of reality, there is no means to manifest it.

So you would advocate for the importance of studying English.

Indeed! I was an English major, and I felt that it opened many doors for me. Moreover, when I reflect on my daily life, I realize that the most hopeful action I take every single day is to read a book.

Reading a book allows you to connect with another person’s thought process, which is deeply impactful. We are more vulnerable to oppression when we are isolated, when we are fragmented. Books serve as a strong conduit for connection. If you are among those who are tending to the fire, nurturing that bond, it is indeed a significant endeavor.