A blue whale captured in September 2010.NOAA

The blue whale ranks as the largest creature on Earth. It ingests vast amounts of minuscule, shrimp-like organisms referred to as krill to sustain a body that can reach lengths of 100 feet (30 meters). Blue whales and other baleen whale species, which strain seawater through their mouths to consume small aquatic life, once thrived in Earth’s oceans. However, during the last hundred years, they were hunted nearly to extinction for their energy-rich blubber.

As whale numbers plummeted, some believed that krill populations would surge in the absence of predators. Yet, that was not the case. Krill numbers also diminished, and neither species has experienced a recovery to date.

A recent hypothesis suggests that whales acted not solely as predators in the marine ecosystem. The nutrients expelled by whales may have served as a crucial fertilizer for these oceanic habitats.

Investigations conducted by oceanographers from the University of Washington lend support to this hypothesis. Their findings reveal that whale feces contain considerable amounts of iron, an essential nutrient frequently lacking in ocean ecosystems, as well as non-toxic varieties of copper, another vital nutrient that can be harmful to marine life in certain forms.

The open-access study, which marks the first exploration of the varieties of these trace metals typically found in whale excrement, was published in January in Communications Earth & Environment.

“We conducted unprecedented measurements of whale droppings to evaluate the significance of whales in recycling crucial nutrients for phytoplankton,” stated the lead author Patrick Monreal, a doctoral student in oceanography at UW. “Our analysis indicates that the drastic reduction of baleen whale populations due to historical whaling could have had broader biogeochemical effects on the Southern Ocean, an area critically important to global carbon cycling.”

The Southern Ocean surrounding Antarctica is home to scant human life but is believed to play a vital role in the world’s climate. Powerful circumpolar currents deliver deep ocean water to the surface. Massive blooms of plant-like entities known as phytoplankton bolster krill populations, which are still collected in unregulated waters today for aquaculture and pet food.

To assess the influence of whale droppings on this ecosystem, the research examined five fecal samples. Two samples originated from humpback whales in the Southern Ocean, while three were from blue whales off the central Californian coast. The samples were gathered when researchers researching whale populations seized an opportunity.

“The fortunate aspect, I suppose, is that whale waste floats,” remarked senior author Randie Bundy, an assistant professor of oceanography at UW. Researchers collect it using a net connected to a jar to gather the substance typically found as a slushy or slurry.

“The prevailing theory is that the whales were indeed contributing nutrients to the ecosystem that these phytoplankton could utilize, leading to increased blooms, subsequently allowing krill to feed on them,” Bundy explained.

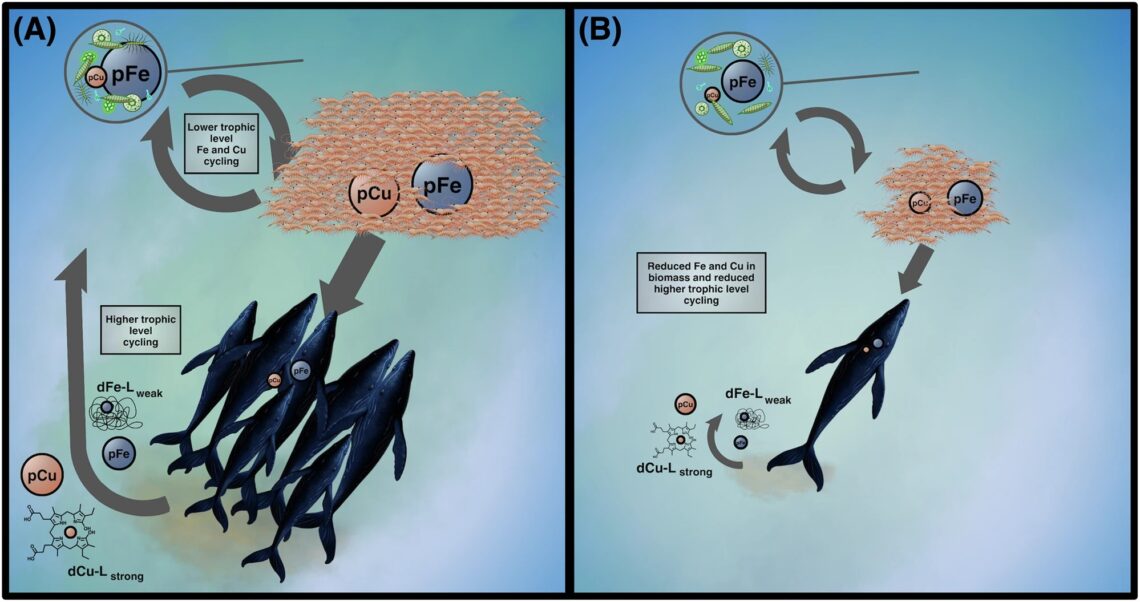

An illustration of the (A) pre-whaling and (B) post-whaling relationships among whales, krill (pink), and photosynthesizing life forms known as phytoplankton (upper left of each panel) in the Southern Ocean. The decline in whale populations in this ecosystem alongside a concurrent decrease in krill in some former whaling regions signifies a substantial reduction in the availability of iron due to the loss of whales and, consequently, micronutrients in whale excrement (lower left).Monreal et al./University of Washington

Previous studies had identified considerable quantities of essential nutrients, such as nitrogen and carbon, within whale fecal samples. The new research focused instead on metals that are limited in supply far from land and often act as limiting factors for marine ecosystem development.

“In the Southern Ocean, iron is recognized as one of the most scarce or limiting nutrients that phytoplankton require to thrive,” Bundy noted.

Results indicated iron’s presence in all samples. The researchers also detected another metal: copper.

“We were taken aback by the quantity of copper found in the whale excrement. Our initial thought was, ‘oh no, could this whale poop actually be toxic?’” Bundy stated.

Further examination revealed that organic molecules known as ligands bound to the copper atoms converted them into a safe form for marine organisms. Other ligands facilitated the accessibility of the iron to living beings. The source of these ligands remains unknown, but researchers suspect they might originate from bacteria residing in the whales’ digestive systems.

Bundy’s research centers on trace metals in ocean habitats. This project began as Monreal’s introductory research project while pursuing his graduate studies but expanded into a larger initiative as data accumulated.

“I believe animals contribute significantly to chemical cycles more than many specialists acknowledge, particularly when considering the ecosystem perspective,” Monreal remarked. “By animals, I truly mean their gut microbiome. Based on our observations, it appears bacteria within the whales’ guts could play a crucial role.”

Lead author Patrick Monreal, a doctoral student from the University of Washington, stands aboard a ship in the Southern Ocean in January 2025. Monreal’s investigation indicates that once-abundant whales in these waters may have also played a role in fertilizing the waters to nurture photosynthetic organisms.Madeline Blount

Co-authors include postdoctoral researcher Angel Ruacho, former doctoral student Laura Moore, and former undergraduate researcher Dylan Hull from UW; Matthew Savoca and Jeremy Goldbogen at Stanford University; Lydia Babcock-Adams from Florida State University; Logan Pallin, Ross Nichols, and Ari Friedlaender at the University of California, Santa Cruz; John Calambokidis at the Cascadia Research Collective in Olympia, Washington; and Joseph Resing.

at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the University of Washington’s Cooperative Institute for Climate, Ocean, and Ecosystem Research. Sponsors include MAC3 Impact Philanthropies, the MUIR Program at the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment, the University of Washington’s Program on Climate Change, and the Ford Foundation.

For further details, reach out to Monreal at [email protected] and Bundy at [email protected]. Please note: Monreal is operating on New Zealand time until mid-February, which may result in delayed replies.