“`html

Health

We recognize exercise is beneficial for you. Why? He’s exploring it.

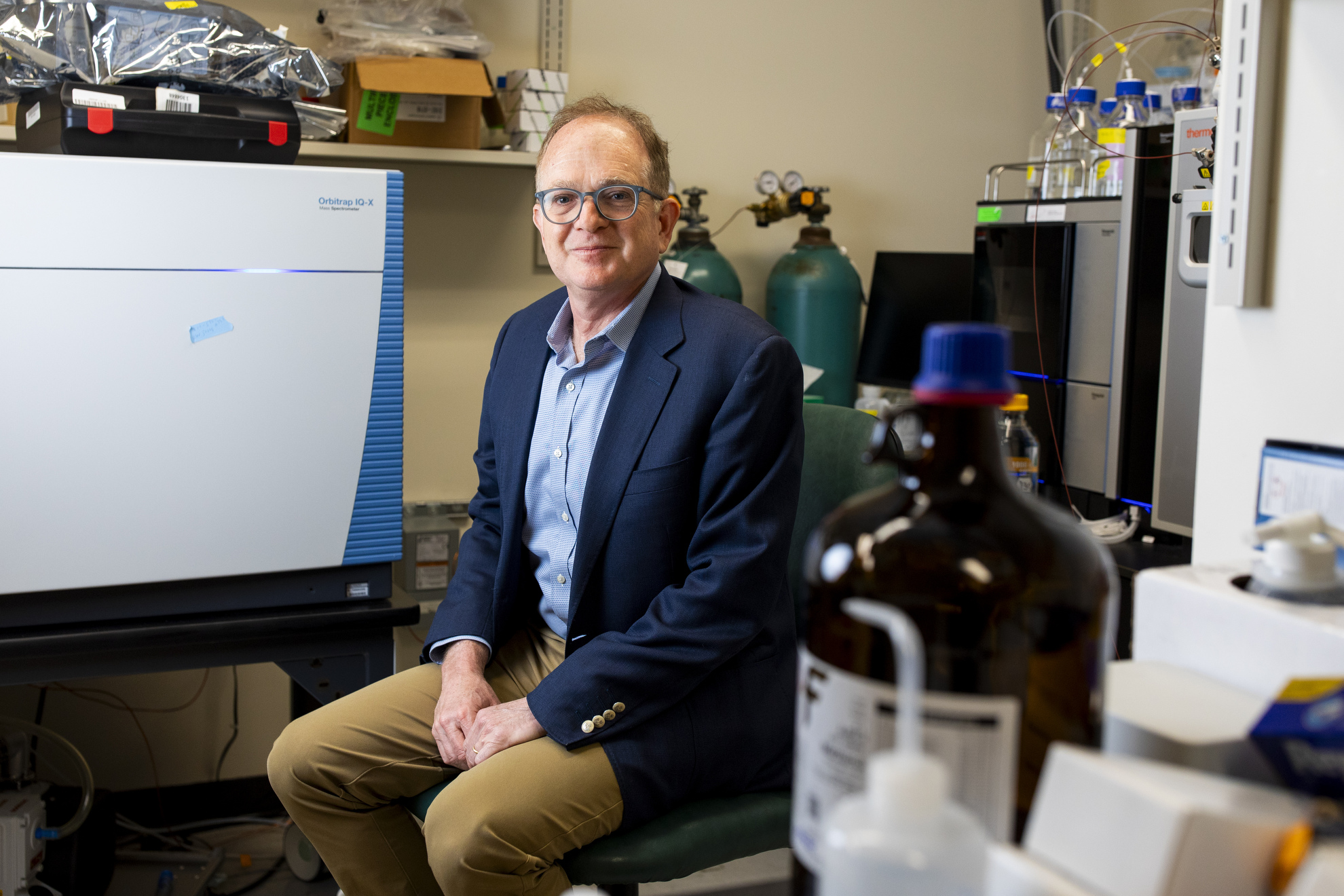

Building on years of study, Robert Gerszten aims to identify movement’s molecular advantages

Robert Gerszten in his laboratory.

Veasey Conway/Harvard Staff Photographer

We understand exercise is advantageous for us — but not precisely why. At Harvard, scholars are working to determine how exercise influences our bodies at the cellular scale.

“It’s been acknowledged since Hippocrates that exercise is linked with health,” stated Robert Gerszten, a professor at Harvard Medical School and chief of cardiovascular medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. “However, the mechanisms through which exercise is advantageous at a molecular level remain poorly elucidated.”

For many years, Gerszten’s laboratory has been addressing this inquiry. Significantly, he has participated in a groundbreaking National Institutes of Health initiative initiated in 1992 known as the HERITAGE Family Study. Utilizing data from over 650 men and women of diverse fitness levels engaging in a 20-week exercise regimen, the study continues to reveal new insights.

In 2021, Gerszten co-authored a paper leveraging HERITAGE data whereby researchers were able to predict with considerable accuracy whether individuals would enhance their cardiovascular condition, and to what extent. The team employed advanced molecular techniques to determine blood-based biomarkers associated with fitness and training response. From the more than 5,000 proteins examined by his laboratory, Gerszten and his colleagues were able to pinpoint 147 that demonstrated strong predictive connections.

“We began to uncover several new biochemicals that hadn’t been documented previously in the realm of exercise physiology,” shared Gerszten.

Building upon this research, Gerszten is a participant in yet another NIH-backed initiative — the Molecular Transducers of Physical Activity Consortium. His laboratory serves as one of the principal chemical analysis facilities evaluating clinical metrics like blood pressure, VO₂ max (a measure of cardiorespiratory fitness), and muscle strength in over 2,000 participants. Furthermore, the team is collecting blood specimens and tissue biopsies both prior to and post 12 weeks of exercise to assess molecular transformations against baseline samples.

“The HERITAGE study served as a precursor for this study,” Gerszten noted. “It was the largest exercise investigation ever conducted, encompassing around 650 individuals, which is roughly a third of the magnitude of this.”

“The concept is, if you identify some pathway that’s providing much of the benefit of exercise, do you really require the exercise?”

Gerszten emphasized that this research isn’t extensive solely because of its magnitude, but also its broad range of patients. There are participants under 18 and over 60. Moreover, from each individual, approximately seven blood samples are obtained, alongside tissue samples, during acute exercise. “Each time,” he stated, “before and after training, you obtain muscle and fat biopsies.”

The researchers aim to gain a deeper understanding of why certain individuals respond more favorably to differing types of workouts, such as running versus weightlifting. They also aspire for their discoveries to result in clinical applications.

“The concept is, if you identify some pathway that’s providing much of the benefit of exercise, do you really require the exercise?” Gerszten posited. “You can envision that for certain individuals, like those in wheelchairs or extremely frail, these potential interventions may be particularly beneficial.”

Initial findings from pre-COVID trials of patients are beginning to be disclosed. Although Gerszten mentioned it may take years before all the data is harvested and analyzed, a distinctive feature of the study is that data is being released publicly on an ongoing basis to enable doctors and researchers to utilize it for their own inquiries.

“This is one of the largest genomic databases,” Gerszten remarked. “So there’s going to be countless eyes on the information. I would emphasize that the primary objective is to disseminate this swiftly for all to analyze.”

This research is funded by the NIH Common Fund and is overseen by a team led by the NIH Office of Strategic Coordination, National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and the National Institute on Aging, with contributions from a trans-agency working group representing numerous NIH institutes and centers.

“`