“`html

Immigration and border enforcement will likely be central themes in U.S.-Mexico interactions under the new Trump administration. However, there is also an escalating water emergency along the U.S.–Mexico frontier impacting tens of millions on both sides, manageable only if the two authorities collaborate.

Climate variations are diminishing surface and groundwater resources in the southwestern U.S. Elevated air temperatures are boosting evaporation rates from water bodies and aggravating drought situations. Mexico, too, is undergoing prolonged droughts and heat waves.

Increasing water consumption is already straining limited resources from nearly all of the regional transboundary rivers, streams, and aquifers. A significant number of these sources are polluted with agricultural chemicals, untreated sewage, and other contaminants, diminishing the usability of available water.

As scholars based in Texas who investigate the legal and scientific facets of water regulations, we understand that communities, farms, and enterprises in both nations depend on these rare water supplies. From our perspective, the present legal framework for managing these resources is inadequate given the dramatic changes in border water conditions.

Unless both countries acknowledge this reality, we contend that water issues in the region are poised to worsen, and resources may never rebound to levels witnessed as recently as the 1950s. Although the U.S. and Mexico have initiated actions to address these challenges by revising the 1944 water agreement, these measures do not represent long-term remedies.

Increased Demand, Decreasing Supply

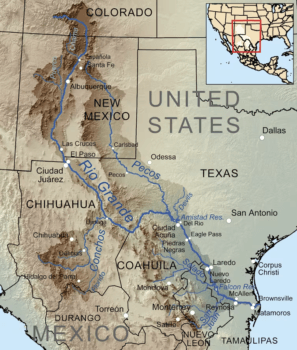

The U.S.-Mexico border area is predominantly arid, with water sourced from a handful of rivers and an uncertain amount of groundwater. The primary rivers crossing the border are the Colorado and the Rio Grande – two of the most water-stressed systems globally.

The Colorado River supplies water to over 44 million individuals, covering seven U.S. states and two Mexican states, 29 Native American tribes, and 5.5 million acres of farmland. Only approximately 10% of its total flow reaches Mexico. Historically, the river flowed into the Gulf of California, but excessive water extraction along its route has caused it to often diminish in the desert since the 1960s.

The Rio Grande provides water for around 15 million individuals, including 22 Native American tribes, three U.S. states, and four Mexican states, along with 2.8 million acres of irrigated land. It delineates the 1,250-mile (2,000-kilometer) Texas-Mexico boundary, meandering from El Paso in the west to the Gulf of Mexico in the east.

Additional rivers that pass through the border include the Tijuana, San Pedro, Santa Cruz, New, and Gila, all of which are considerably smaller and less economically influential than the Colorado and the Rio Grande.

At least 28 aquifers – subterranean rock formations that hold water – also span the border. With some exceptions, very limited data on these shared resources is available. One known fact is that many of them are significantly overutilized and polluted.

Nonetheless, dependency on aquifers is increasing as surface water sources diminish. Approximately 80% of groundwater utilized in this border zone is directed towards agriculture. The remaining supply is used by farmers and industries, including vehicle and appliance manufacturers.

Over 10 million individuals in 30 cities and communities throughout this border region depend on groundwater for household purposes. Numerous communities, such as Ciudad Juarez; the sister cities of Nogales in both Arizona and Sonora; and the sister cities of Columbus in New Mexico and Puerto Palomas in Chihuahua, obtain all or most of their freshwater from these aquifers.

A Flourishing Region

Approximately 30 million individuals reside

“`within 100 miles (160 kilometers) from the border on both fronts. In the forthcoming 30 years, that number is predicted to double.

The demand for water in municipal and industrial sectors across the region is also anticipated to rise. In Texas’ lower Rio Grande Valley, municipal consumption alone could more than double by 2040.

Simultaneously, with the escalation of climate change, experts forecast that snowmelt will diminish and evaporation rates will rise. The baseflow of the Colorado River – the segment of its volume stemming from groundwater rather than precipitation and snow – may reduce by nearly 30% over the next 30 years.

Forecasts indicate that precipitation patterns throughout the area will be unpredictable and inconsistent for the foreseeable future. This pattern will lead to more severe weather occurrences, including droughts and floods, resulting in widespread damage to crops, industrial operations, human health, and the ecosystem.

Additional strain arises from expansion and development. Both the Colorado River and Rio Grande are contaminated by effluents from agricultural, municipal, and industrial activities. Cities on either side of the border, particularly on the Mexican side, have a longstanding history of discharging untreated sewage into the Rio Grande. Among the 55 water treatment facilities positioned along the border, 80% reported ongoing maintenance, capacity, and operational challenges as of 2019.

Water shortages in the border region have already ignited local and bilateral frictions. Conflicting water users are struggling to satisfy their requirements, while both the U.S. and Mexico are facing difficulties in fulfilling treaty obligations for water distribution.

Cross-border Water Governance

Mexico and the United States oversee water distribution in the border region primarily under two treaties: a 1906 agreement concerning the Upper Rio Grande Basin and a 1944 treaty addressing the Colorado River and Lower Rio Grande.

According to the 1906 treaty, the U.S. is required to deliver 60,000 acre-feet of water to Mexico where the Rio Grande meets the border. This figure can be adjusted downwards during periods of drought, which have been frequent in recent decades. An acre-foot represents sufficient water to inundate an acre of land to a depth of 1 foot – approximately 325,000 gallons (1.2 million liters).

Allocations specified in the 1944 treaty are more complex. The U.S. must provide Mexico with 1.5 million acre-feet of Colorado River water at the border – however, as with the 1906 treaty, reductions are permissible during extraordinary drought circumstances.

Until the mid-2010s, the U.S. fulfilled its complete obligations annually. However, since then, regional drought and climate change have significantly diminished the Colorado River’s flow, necessitating major allocation reductions for both the U.S. and Mexico.

In 2025, states within the U.S. portion of the lower Colorado River basin will undergo a decrease of over 1 million acre-feet compared to earlier years. Mexico’s allotment will decrease by about 280,500 acre-feet according to the 1944 treaty.

This arrangement provides each nation with allocated shares of flows from the Lower Rio Grande and certain tributaries. Regardless of water availability or climatic conditions, Mexico is also obligated to deliver to the U.S. a minimum of 1,750,000 acre-feet from six specified tributaries, averaged over five-year periods. Should Mexico fall short in one cycle, it can compensate for the deficit in the next five-year cycle but cannot postpone repayment beyond that.

Since the 1990s, exceptional droughts have led to Mexico missing its delivery commitments three times. Although Mexico has reimbursed its water deficits in subsequent cycles, these failures heightened diplomatic tensions, resulting in eleventh-hour negotiations and large-scale water transfers from Mexico to the U.S.

Mexican farmers in the Lower Rio Grande irrigation districts, who had to bear the brunt of these reductions, felt deceived. In 2020, they held protests, confronting federal soldiers and temporarily taking over a dam.

U.S. President Donald Trump and Mexican President Claudia Scheinbaum evidently recognize the political and economic significance of the border region. However, if water scarcity escalates, it could overshadow other border concerns.

In our perspective, the optimal way to avert this situation would be for both nations to acknowledge that conditions are deteriorating and revise the existing cross-border governance framework to reflect today’s emerging water realities.

This article first appeared in The Conversation.

The post Water Is The Other US-Mexico Border Crisis, And The Supply Crunch Is Getting Worse showed up first on Texas A&M Today.