The effectiveness of a snake’s venom to incapacitate its target could rely on factors beyond merely its potency or the prey’s resistance to the toxin; it also appears to be influenced by the climate, asserts a researcher from the University of Michigan.

“Even among various populations of the same species of snake, consuming identical prey, we observe evolutionary variations in their venoms,” explained Matthew Holding, an evolutionary biologist affiliated with the University of Michigan Life Sciences Institute and principal author of the research published in Biology Letters.

“In this investigation, we sought to delve into the factors that drive these variations in the natural coevolutionary dynamics between snakes and their prey.”

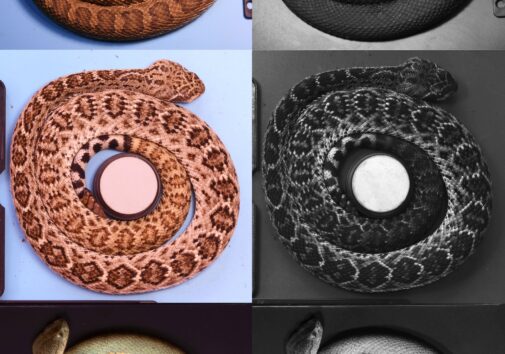

Holding and his team from the University of Nevada Reno and University of Utah scrutinized the response of blood serum samples from wild woodrats to rattlesnake venom. Woodrats, as natural prey for rattlesnakes, have developed resistance to their venom: They can withstand between 500 to 1,000 times the quantity of venom that would be lethal to a standard laboratory mouse. This resistance is attributed to proteins present in the blood of the woodrats that can neutralize the venom.

In this study, the researchers employed serum samples from rats that had been subjected to either elevated (29.5°C) or lower (21°C) temperatures. They discovered that the samples from the warm group were more effective at inhibiting the venom’s potency compared to those from the colder group. This finding serves as the initial experimental evidence indicating that a rodent’s environmental temperature can influence its blood-based venom resistance, stated Holding.

“These samples were collected in Utah and subsequently frozen, thawed, and analyzed at room temperature here in Michigan—and we could still observe a notable distinction between rats from the cold and warm groups,” Holding remarked. “That indicates that it’s the specific content of their blood that is altering in reaction to environmental temperature, resulting in substantial differences in the serum’s capacity to inhibit snake venom.”

The research team also examined the variations in serum from woodrats that were given standard rat food versus those that consumed more of their natural diet, primarily composed of a highly toxic plant known as creosote bush. Previous studies have shown how woodrats can tolerate nearly lethal food. However, this latest research suggests that the consumption of the toxic plant may come with a drawback: The serum from rats with higher creosote intake was less efficient at inhibiting rattlesnake venom.

“In both the temperature and dietary assessments, there seems to be a physiological trade-off for coping with the various stresses faced by the animal,” remarked Denise Dearing, a distinguished professor of biological sciences at the University of Utah and senior author of the research.

“If the animals are channeling energy into maintaining warmth or digesting a toxic diet, they may possess reduced energy for generating these venom-resistant proteins. Activating their internal heater to remain warm appears to impose a greater physiological toll regarding venom resistance.”

The research team aims to explore which of the numerous proteins present in woodrat serum are undergoing changes, as this may provide further insight into how these animals manage to neutralize rattlesnake venom.

“The exploration of venoms and the animals that withstand them has revealed several highly potent pharmacologically active compounds and has led to the formulation of medications such as anticoagulants and even Ozempic,” Holding noted. “I am genuinely fascinated by the foundational science of how environmental factors can influence coevolutionary relationships between snakes and their prey across different locations. Moreover, it can lead to the identification of powerful compounds with potential significant applications.”

This investigation received funding from the National Science Foundation and the University of Utah. The animal experiments for this study were sanctioned by the University of Utah Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and adhered to institutional protocols.

In addition to Holding and Dearing, the authors of the study include: Alexandra Coconis and Marjorie Matocq from the University of Nevada Reno, and Patrice Connors from the University of Utah.