Arts & Culture

Revealing the hue of history

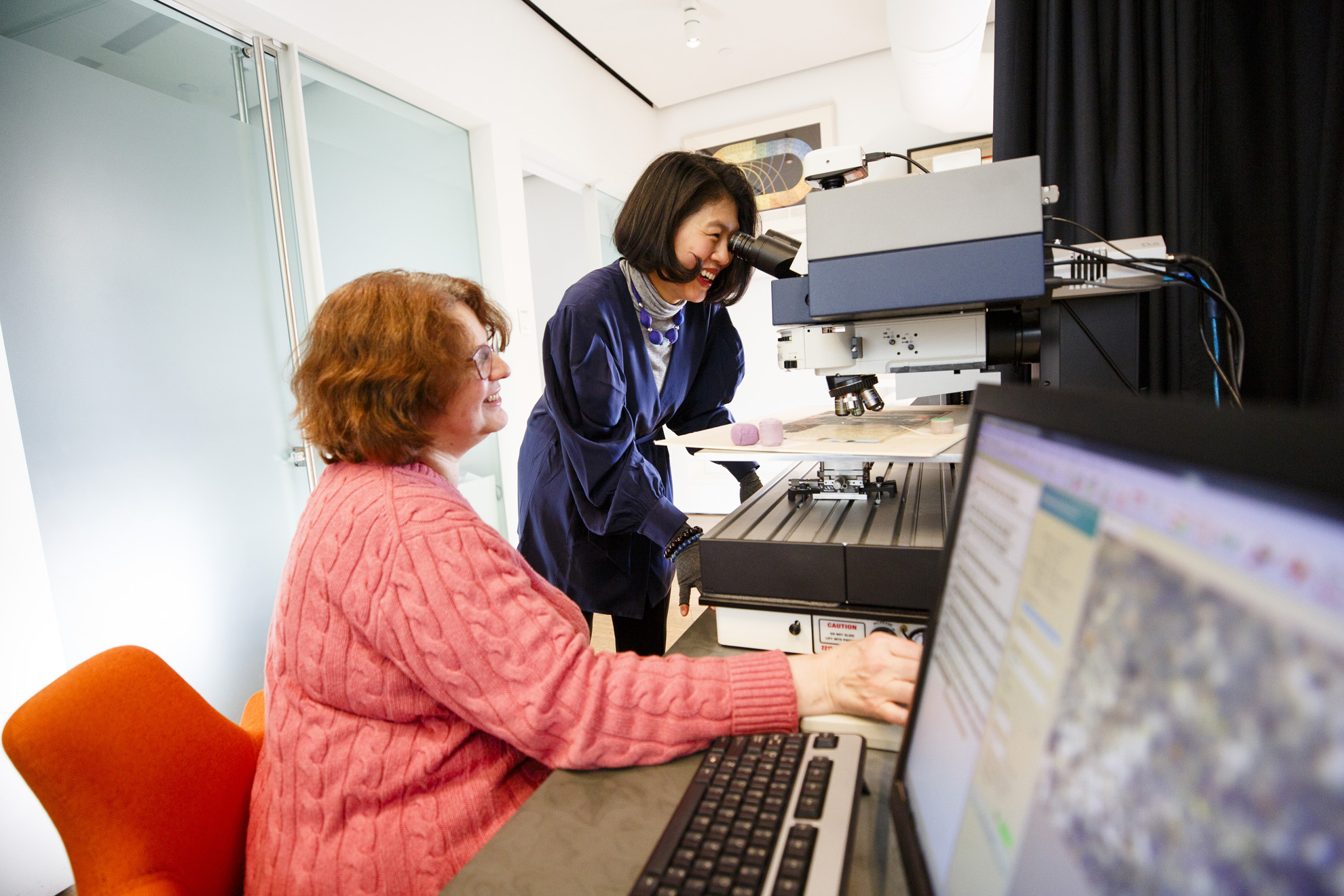

Jinah Kim.

Photo by Grace DuVal

Initiative charts colors utilized in South Asian artistry

When Jinah Kim discovered in 2016 that the Museum of Fine Arts’ conservation scientist Michele Derrick had found cobalt in a 15th-century Indian manuscript, she was faced with a clear illustration: the document had likely been refurbished later, possibly using synthetic pigments. After all, cobalt-based pigments manufactured in Europe, such as smalt, were extensively imported into South Asia only during the 17th century, and synthetic cobalt blue gained popularity solely in the early 19th century.

However, Kim, who was compiling information on pigments for her second publication, was not persuaded.

“What do we understand regarding authentic pigment application in this area during this era?” Kim, George P. Bickford Professor of Indian and South Asian Art in the Department of History of Art & Architecture, pondered. “Must it all originate from Europe? It’s feasible that there are indigenous insights into colorants that remain unknown.”

Further examination by Katherine Eremin, Patricia Cornwell Senior Conservation Scientist at Harvard Art Museums, corroborated that the smalt discovered in the Jain manuscript possessed a distinct composition from the European-made smalt, signifying it came from an alternative origin.

This was a “eureka” moment for Kim, who theorized that some pigments thought to have entered South Asia as imports from Europe may have actually been in use there long before. This conclusion birthed the “Mapping Color in History Project,” an ongoing initiative since 2018 aimed at establishing an object-based pigment database for historical examinations of art from this region.

“I recognized that many pigment databases presently available are founded upon a Western European framework, because that has been the focus of research,” Kim stated. “When considering Asian materials, particularly South Asia, the Himalayas, and Southeast Asia, the vibrancy is remarkable, yet the foundational understanding of accessible colorants remains largely unknown.”

“I recognized that many pigment databases presently available are founded upon a Western European framework, because that has been the focus of research.”

Jinah Kim

The open-access database permits users to search by artwork title, keyword, pigment, hue, or element and sift results by artist, date, and other criteria. There is also a map to explore by geographic origin. On each artwork’s page, users can see an analysis of the pigments identified in the piece, the method employed for their identification, and the scientists’ level of confidence. Kim aims for the database to be beneficial for “anyone intrigued by color,” encompassing individuals in the cultural heritage sector, art historians, curators, educators, and students.

Kim portrays Mapping History as highly collaborative, uniting professionals across digital humanities, conservation science, and art history.

“I characterize it as a three-pronged stool,” Kim commented. “It cannot be accomplished by a single individual due to the necessity for diverse expertise. Computer programming is required to construct this database, material analysis is necessary, and art historical research is essential for contextualizing it in history and time.”

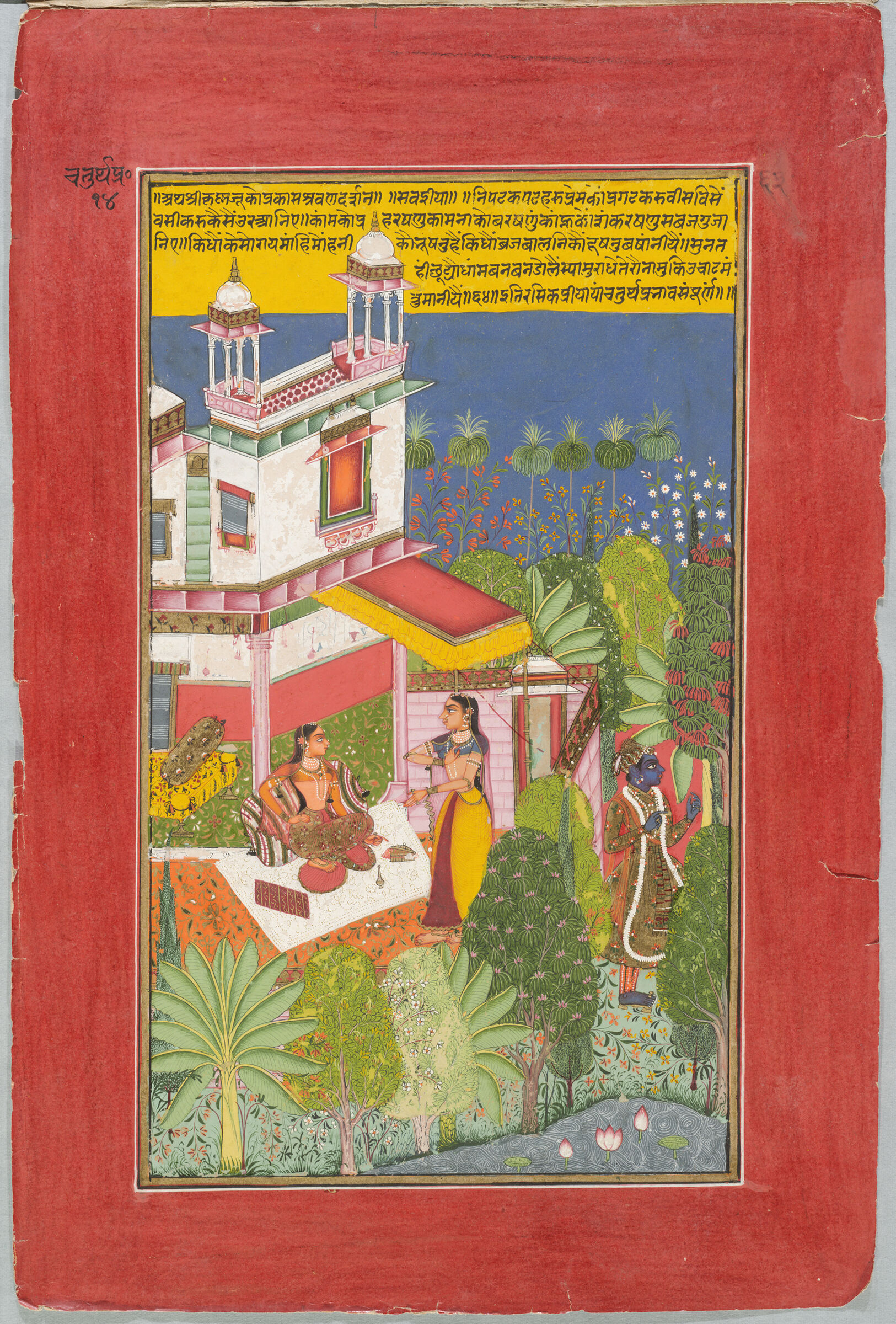

“Hindu Goddess Ganga with Two Female Attendants Carrying Fly-Whisks,” Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Gift of James E. Robinson III in honor of Stuart Cary Welch and Alve John Erickson

Photo © President and Fellows of Harvard College, 1997.236

Kim collaborated with Rashmi Singhal and theArts & Humanities Research Computing (DARTH) group along with Jeff Steward from Harvard Art Museums discussed the technological components of the initiative. The database was developed from the ground up.

Tracy Stuber, a digital humanities expert with DARTH who serves as a link between the research groups and software developers, noted that the Mapping Color website stands out because it connects two forms of data that are typically isolated and utilized by different audiences: information regarding the artwork itself and details from scientific evaluations.

“Given that we have a general understanding of when or where an artwork was created, we can assert, ‘This pigment that we’ve pinpointed in this artwork was therefore produced roughly in that location at that period,’” Stuber mentioned. “Connecting them together in a database not only renders that data available to the other audience but also fosters enhanced collaboration and dialogue between those two fields.”

Katherine Eremin (left) and Jinah Kim examine a manuscript under a microscope.

Photos by Grace DuVal

Engaging with ancient art implies that researchers generally cannot extract samples for examination. According to Eremin, one of the project’s principal collaborators, the scientists associated with Mapping Color predominantly utilize non-invasive techniques, relying on them 99% of the time.

When Eremin assesses a piece of art, she usually begins with imaging that can differentiate specific pigments that react distinctively in infrared and ultraviolet light. For instance, Indian Yellow emits a glow under UV illumination. She also inspects the pigment through a microscope to analyze the mixture of colors employed.

“At first glance, you might think, ‘Oh, that’s lovely,’ but then you actually peer through the microscope and observe the intricate details,” she stated. “You may assume, ‘It’s merely blue,’ but upon closer examination, you discover it’s a blend of various elements.”

Next, she attempts to identify components using x-ray fluorescence, determining which unique x-rays are emitted from the artwork. For example, a green hue might be classified as copper green if copper rays are detectable or as yellow orpiment (an arsenic sulfide mineral) mixed with blue if arsenic rays are apparent. To extract insights at the molecular scale, Eremin employs Raman spectroscopy, a non-invasive laser technique that can ascertain whether a copper green is malachite or atacamite.

On rare occasions, if a piece of art is already peeling, it may inspire discussions among curators, conservators, and scientists about the possibility of taking a sample. Using an infrared light method known as Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy, Eremin examined a minuscule particle retrieved from a deteriorating 16th-century Indian manuscript, and discovered that kaolin clay was utilized for the white border detail.

These discoveries provide valuable insights into the vision of the artists. In the examination of a 1588 “Divan of Anvari” manuscript series, Mapping Color scientists found that the artist employed an Indian yellow pigment for the vibrant yellow of the figure’s attire, while orpiment, an older arsenic sulfide yellow, was used for accentuating leaves on a tree.

“What this indicates to me is that artists are striving to achieve that pure form of radiant yellow, and they are distinguishing between various shades,” Kim remarked.

“Krishna’s Manifest Vision through Sound (Kavitt),” from a Rasikapriya series, Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Gift of Philip Hofer

Photo © President and Fellows of Harvard College, 1984.458

The Mapping Color in History Project has also partnered with traditional Indian painter Babulal Marotia, based in Jaipur, to examine samples of pigments he incorporates in his studio work. Studying materials used by contemporary artists like Marotia, who continue artistic traditions that have been handed down through generations, is invaluable, Kim noted.

“You can’t dismantle a 700-year-old painting to discover what has occurred.” Kim observed. “This provides us an access point to that historical moment through these materials still in use.”

Pinpointing the origin locations of the paintings in the database is challenging, as historical artworks from South Asia often lack specific information regarding their date, locale, and artist.

Identifying the origin locations of the artworks in the database is complex, as historical pieces from South Asia frequently lack detailed data about their date, location, and creator.

“If you search for a certain Indian painting in a museum’s database, it may indicate, ‘North India, 17th-18th century,” Kim shared. “You cannot accurately map ‘North India, 17th -18th century’ at any given time and place. That’s where we need to conduct further research on objects, unearth more pertinent information, and perform comparative studies to refine our attributions.”

Kim has compiled a list of suggestions for enhancing the database (including adding more artworks, visualization tools, and indicators of certainty) that she is eager to implement.

“I aim to understand specific trends, I want to identify patterns, and I aspire to uncover aspects that were previously unnoticed,” Kim stated. “However, a database is only as effective as the data it contains, so considerable effort remains to be done.”

Some of the efforts involved in the database have been funded by grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities.