Illustration by Judy Blomquist/Harvard Staff

Nation & World

U.S. learners need to commence attending

Outlining latest recovery scorecard, Ed School researcher advocates broader measures to diminish absenteeism and a clearer focus on targeted catch-up efforts

In the most recent report from the Education Recovery Scorecard, jointly authored by Harvard’s Thomas Kane and released on Tuesday, researchers analyzed academic recovery in mathematics and reading for specific school districts accommodating 35 million learners across 43 states. Key findings include: Students are progressing in the “wrong direction” regarding reading; tutoring appears to be beneficial; and ongoing absenteeism adversely affects student performance.

The report — a partnership among the Center for Education Policy Research at Harvard, the Educational Opportunity Project at Stanford University, and professors at Dartmouth College — surfaces months after federal relief funding for K-12 schools lapsed. Federal aid totaling approximately $190 billion was allocated to educational institutions, which had until September to utilize the funds.

In this revised interview with the Gazette, Kane, who directs the Center for Education Policy Research and is a professor at Harvard Graduate School of Education, outlines both the latest findings and the initiation of a Harvard-led endeavor to assist states in identifying and disseminating evidence-based strategies to curtail chronic absenteeism and enhance reading and mathematics skills.

You’re currently in the third year of producing the scorecard. How would you characterize the student recovery narrative at this juncture?

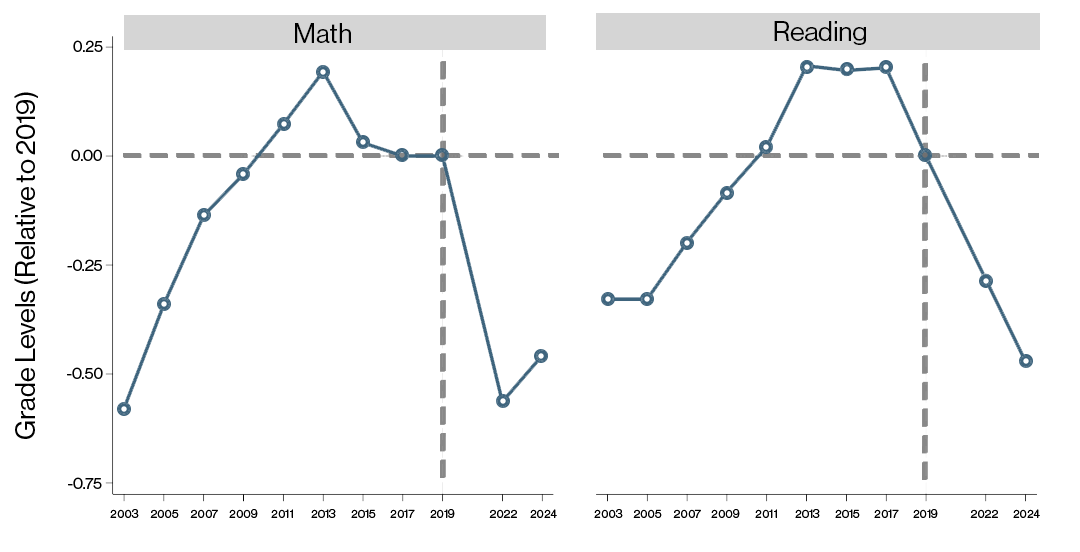

Students have continued to slowly recoup in mathematics, though the average student still lags by nearly half a grade level. In reading, instead of recovering, students are regressing, losing more ground between 2022 and 2024. The decline in literacy occurred despite efforts to implement the “science of reading” in several states, including Massachusetts.

Literacy levels were already declining even prior to the pandemic, correct?

There has been a gradual decrease since 2015, particularly among individuals with poor reading skills. Not all the declines that we observe are solely attributed to the disruptions in either in-person or remote instruction during 2020 and 2021. Some of the decline relates to trends that initiated before the pandemic.

National test scores (Grades 3-8, 2003-2024)

However, some of it has been influenced by the trends that emerged during the pandemic. For instance, if the pandemic represented an earthquake, the subsequent increase in absentee rates has been a tsunami, continually disrupting education.

There are instances of success that you mention in certain high-poverty districts, such as Compton, California, and Ector County in Texas. What has contributed to these successes?

It’s premature to conclude which strategies were effective generally, but we can notice the districts that have made progress and we are beginning to understand their approaches. For example, in Ector County, which encompasses Odessa, the district transitioned to performance-based contracts for tutors. Tutoring contractors received payment only if students achieved specified targets regarding attendance and improvements in mathematics and reading scores. Similarly, other areas like Birmingham, Alabama, employed math coaches to assist teachers in enhancing mathematics proficiency. Thus, there wasn’t a singular strategy utilized by successful districts. The most broadly applicable evidence of effectiveness has been related to high-dosage tutoring and summer learning programs.

The narrative suggests that changes occurred not primarily at the state level, but rather from district to district. Can you elaborate on the variances in test scores?

Ninety percent of the federal pandemic relief was allocated directly to school districts. The federal Department of Education and state educational departments had very limited authority to coordinate initiatives or prompt districts to allocate funds in specific manners. This represented a stark instance of devolution, directing funds straight to local districts for their discretion. Some districts proved to be more effective than others in facilitating student recovery.

Was the federal relief funding effective?

Among districts with comparable poverty rates and characteristics, those that received greater federal funding progressed more swiftly. The impact per dollar was approximately consistent with what prior research indicated one might expect from a general revenue increase. Ultimately, the efficacy was contingent on how districts chose to spend the funds. In California, where we had clearer insights into expenditure, districts that allocated more towards academic interventions, such as tutoring and summer programs, rather than universal salary increases, demonstrated quicker recovery.

The

The diminished effect of the pandemic relief on educational recovery stemmed from the American Rescue Plan legislation; it provided considerable leeway for local communities to determine how to allocate the funding. They were only obligated to devote 20 percent towards academic recuperation. Some prioritized academic recovery more than others.

The report indicates a rise in socioeconomic and racial inequalities in math and, to a lesser degree, reading performance. Can you elaborate on that trend?

Horace Mann famously characterized public schools as “the balancing mechanism of the social system.” We certainly observed that principle during the pandemic. When schools shuttered, the losses were more severe in districts with higher poverty levels. This trend has persisted as chronic absenteeism has increased nationwide. While absenteeism has risen in most districts, it has escalated more significantly in higher-poverty schools. Each missed school day is going to be more detrimental for students in those districts.

“If the pandemic was an earthquake, the ensuing hike in absenteeism has been a tsunami that continues to disturb learning.”

Veasey Conway/Harvard Staff Photographer

With all federal relief funds now expended, your focus seems to be turning from immediate recovery actions to long-term reform. What should the future priorities be for states and districts?

We’re attempting to steer the dialogue away from arguing about the usage or misusage of federal funds toward determining what actions must be taken moving forward. The primary focus should be on securing resources to maintain targeted academic catch-up strategies, such as tutoring and summer education. For instance, states are permitted to allocate 3 percent of federal Title I funds for direct student assistance like tutoring. At present, only one state is utilizing that option — Ohio.

Secondly, we must undertake a widespread initiative to reduce absenteeism. Until now, we have placed the responsibility for recovery solely on the shoulders of principals, superintendents, and educators. However, reducing absenteeism is one of the few areas where community leaders beyond schools could assist right now. This could involve public awareness campaigns or science museums backing extracurricular activities in schools to enhance their appeal to students. Employers could inquire if their staff needs flexibility for school drop-off and pick-up schedules.

A third approach is for educators to notify parents when their child is not performing at grade level. Right from the onset of the recovery, surveys have indicated that parents underestimate the pandemic’s effect on their child’s educational progress. Teachers are aware that students are falling behind, yet it hasn’t reflected in the grades they assign. If parents persist in believing their children are doing well, they won’t enroll them in summer learning programs, may be less concerned about absenteeism, and might resist necessary changes, such as extending the school year, to help students catch up.

Your research center recently unveiled an initiative aimed at enabling states and districts to learn from one another. How will this project operate?

One potential advantage of the U.S. educational system is the variety of solutions states and districts are opting for to address common challenges like absenteeism and falling literacy rates: “science of reading” initiatives differ widely among states; numerous districts have implemented cellphone prohibitions, although not universally. I label it a “potential advantage” because, to gain from it, we must ascertain which interventions are effective and which are not. States cannot gain insights solely from examining situations within their own borders; they must also observe what is proving effective in other states.

Regrettably, no one is coordinating a cross-state initiative focused on effectiveness. Even if the policy discourse in D.C. were less contentious, it would be challenging for the federal government to assess the effectiveness of state reforms. I believe that a national institution like Harvard can fulfill this role. We are launching a cross-state initiative titled the “States Leading States” project. We will collaborate with a group of four or five states over the coming years to evaluate the effectiveness of various policies — including those aimed at enhancing literacy, curtailing chronic absenteeism, and improving middle school mathematics. We will partner with states to discern what is working and subsequently disseminate our findings to other states, through inter-state organizations like the National Council of State Legislators, the National Governors Association, and the Council of Chief State School Officers. I can’t think of anything more critical at this moment than supporting those state leaders who are prepared to adhere to the evidence.