In the investigation of why and how animals appear the way they do, color takes precedence—at least within the spectrum visible to humans.

A study at the University of Michigan explored a spectrum that humans typically overlook: ultraviolet coloration. By examining snakes, the researchers classified how these creatures employed patterns of UV color and investigated the elements that drive the evolution of UV color in snakes.

The researchers found that UV color is commonly present throughout the entire snake phylogenetic tree and is often utilized for evading predators, notes study co-author Hayley Crowell, a graduate student in the U-M Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology.

Published in Nature Communications, their research also underlines that scientists may be neglecting how an entire group of organisms might be utilizing color.

“Most studies on UV color are conducted in systems that we traditionally regard as vibrant and colorful, like birds, flowers, and butterflies, yet much of this color research is inherently biased by human color perception,” Crowell stated.

“This research primarily concentrates on mating or reproductive systems, such as UV ‘nectar guides’ in flowers that assist in directing insects to sections of the flower vital for pollination. However, there exist numerous groups, like snakes, that aren’t commonly acknowledged as colorful study subjects.”

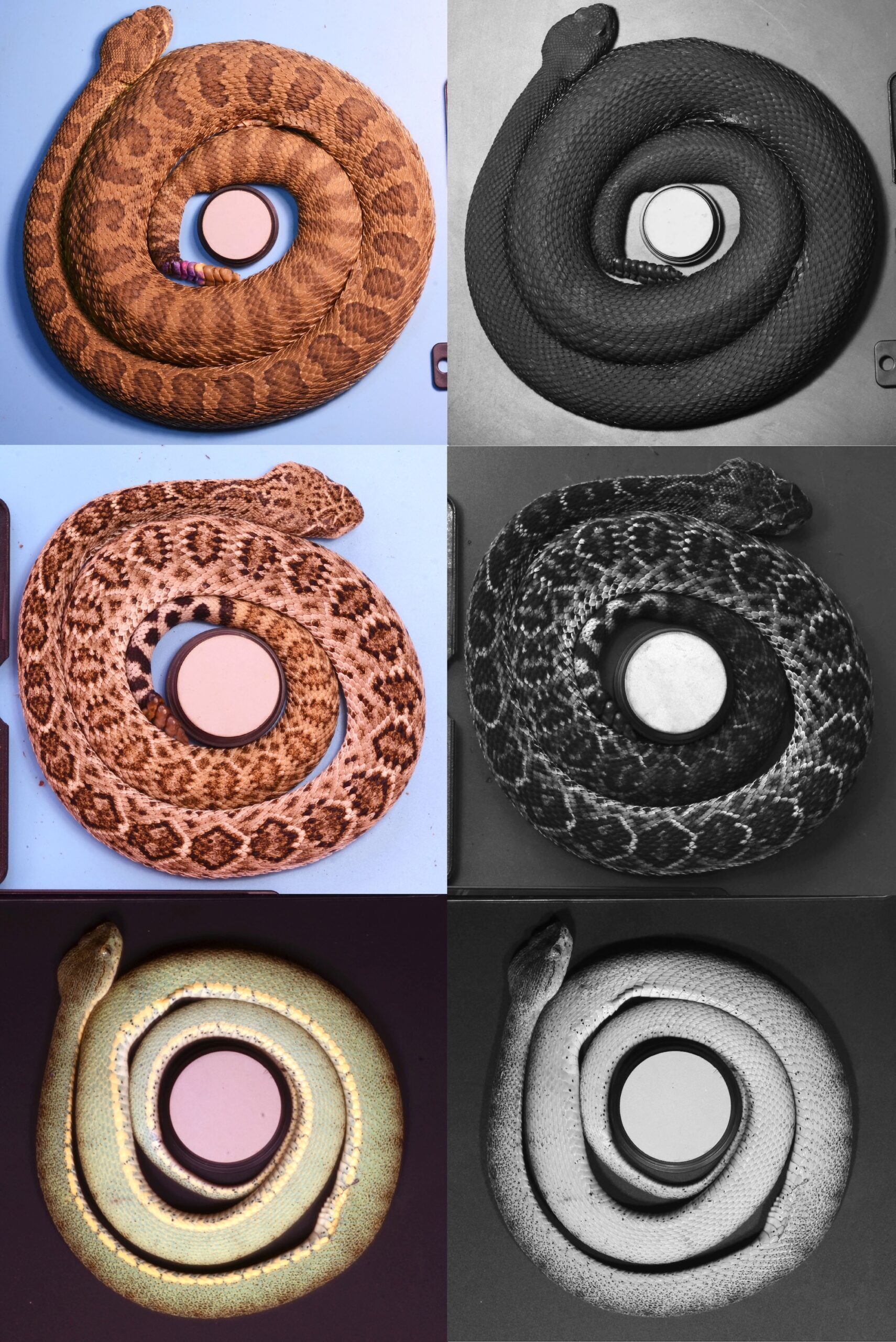

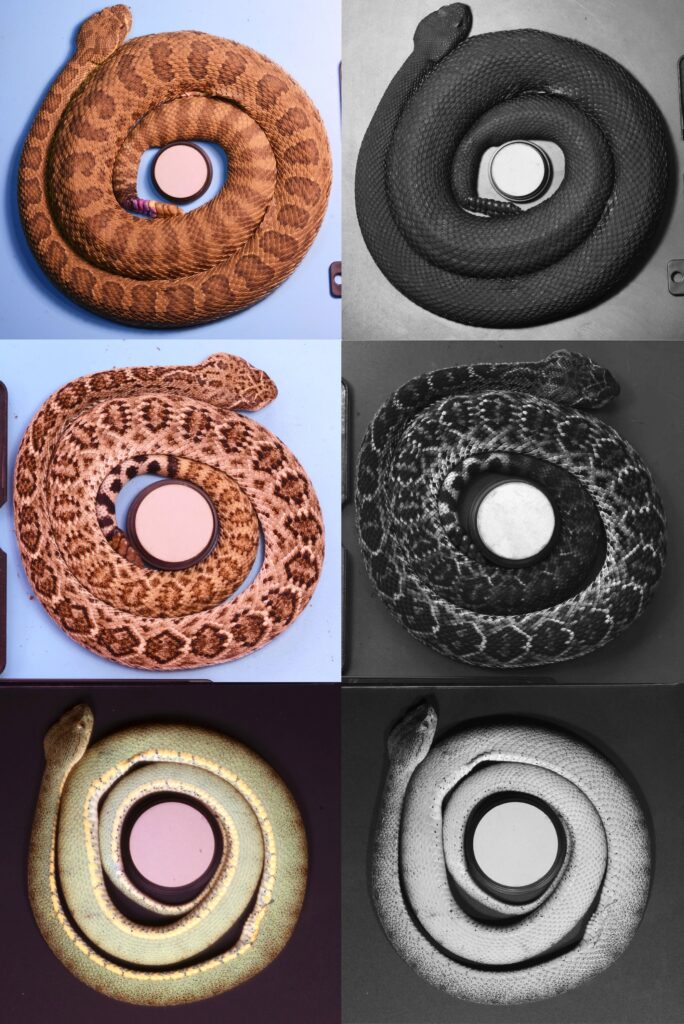

The research assessed 110 snake species spanning regions from Colorado to Peru, many of which possess visual systems that can detect UV color in ways beyond human capability. Crowell and colleagues captured images of the snakes using a camera equipped with specialized lenses and light filters to discern what types of ultraviolet colors they were reflecting. They did not explore visible UV fluorescence using a black light—instead, they investigated genuine UV colors that are imperceptible to humans.

Then, the researchers examined numerous variables to determine which correlated with the presence or absence of UV color across different species. Factors included the age and gender of the snakes, their habitat types, the species’ evolutionary lineage, and how conspicuous a snake’s coloring makes it to predators like birds, mammals, and other snakes.

The most significant correlation between UV color and snakes? Their ecological context, or the interactions between them and their surrounding environment. For instance, arboreal snakes—those that inhabit trees and are typically nocturnal—exhibited the highest amounts of UV color. Why is this? Crowell hypothesizes it relates to camouflage.

Birds, which can also perceive UV color, constitute one of the biggest threats to snakes. Arboreal snakes hunt at night and rest during daylight hours. Having a substantial amount of UV color at night poses no issue, but possessing it during the day may offer protective benefits: Leaves, lichens, and epiphytes—plants and organisms resembling plants that grow on other plants, such as ferns and orchids—can also reflect significant amounts of UV light. Consequently, having UV coloration could provide concealment when birds are foraging.

Among the study’s surprising revelations was the absence of UV color disparities between male and female snakes, highlighting the notion that UV coloration is not linked to reproductive characteristics such as mate selection in serpents, states co-author Alison Davis Rabosky, an associate professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at U-M.

“Given that reproductive processes influence UV color evolution in numerous other species, the lack of sexual distinctions in snakes was unexpected,” remarked Davis Rabosky. “However, I don’t believe snakes are truly an anomaly exhibiting color ‘differently’ from other creatures. Rather, I think we researchers have simply overlooked a significant amount of UV coloration in cryptically pigmented species, particularly in insects. They represent the next frontier.”

The observation that there was no distinction in UV coloration between genders was particularly astonishing, given the close affinity between snakes and lizards, noted study co-author John David Curlis, a postdoctoral fellow in ecology and evolutionary biology at U-M.

“Sexual dimorphism, where males appear distinct from females, is exceedingly prevalent in lizards, with many species characterized by males showcasing vibrant colors and prominent ornaments, while females tend to be more muted or camouflaged,” he explained. “The reality that snake colors did not vary between sexes may indicate that sexual selection plays a lesser role in the color evolution of snakes compared to lizards.”

However, the outcomes aren’t strictly binary. Crowell explains that another group of snakes examined in the research, which appeared almost indistinguishable within the “visible” spectrum, belonged to the same species, were of the same gender, and were collected from identical locations. One snake exhibited a bright UV reflection on its back, while another showed none whatsoever.

They discovered that even if two snake species are closely connected, they might not exhibit similar degrees of UV coloration—in fact, some of the most significant color variations were found within the same genus of snakes. Both highly UV-reflective and less reflective snakes were vipers, and the researchers noted that juvenile snakes typically displayed more UV color compared to adult snakes.

Nonetheless, their research aids in elucidating what it means for animals to utilize color—not merely the colors observable to humans, but also those perceptible to other organisms.

“What’s truly remarkable about this study is that we were able to analyze UV color patterns across such a vast array of species and individuals,” stated co-author Hannah Weller, a postdoctoral research associate at the University of Helsinki. “This extraordinary dataset has significantly contributed to our understanding of just how variable a trait like this can be, even in a group where we wouldn’t typically anticipate it.”

The researchers aspire for their study to motivate more scientists to explore UV coloration across various organisms.