Arts & Culture

‘Two Human Beings,’ repeatedly

Edvard Munch, Two Human Beings (The Lonely Ones), 1906–8. Oil on canvas. Harvard Art Museums/Busch-Reisinger Museum, The Philip and Lynn Straus Collection, 2023.551. Photo: © President and Fellows of Harvard College; courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums.

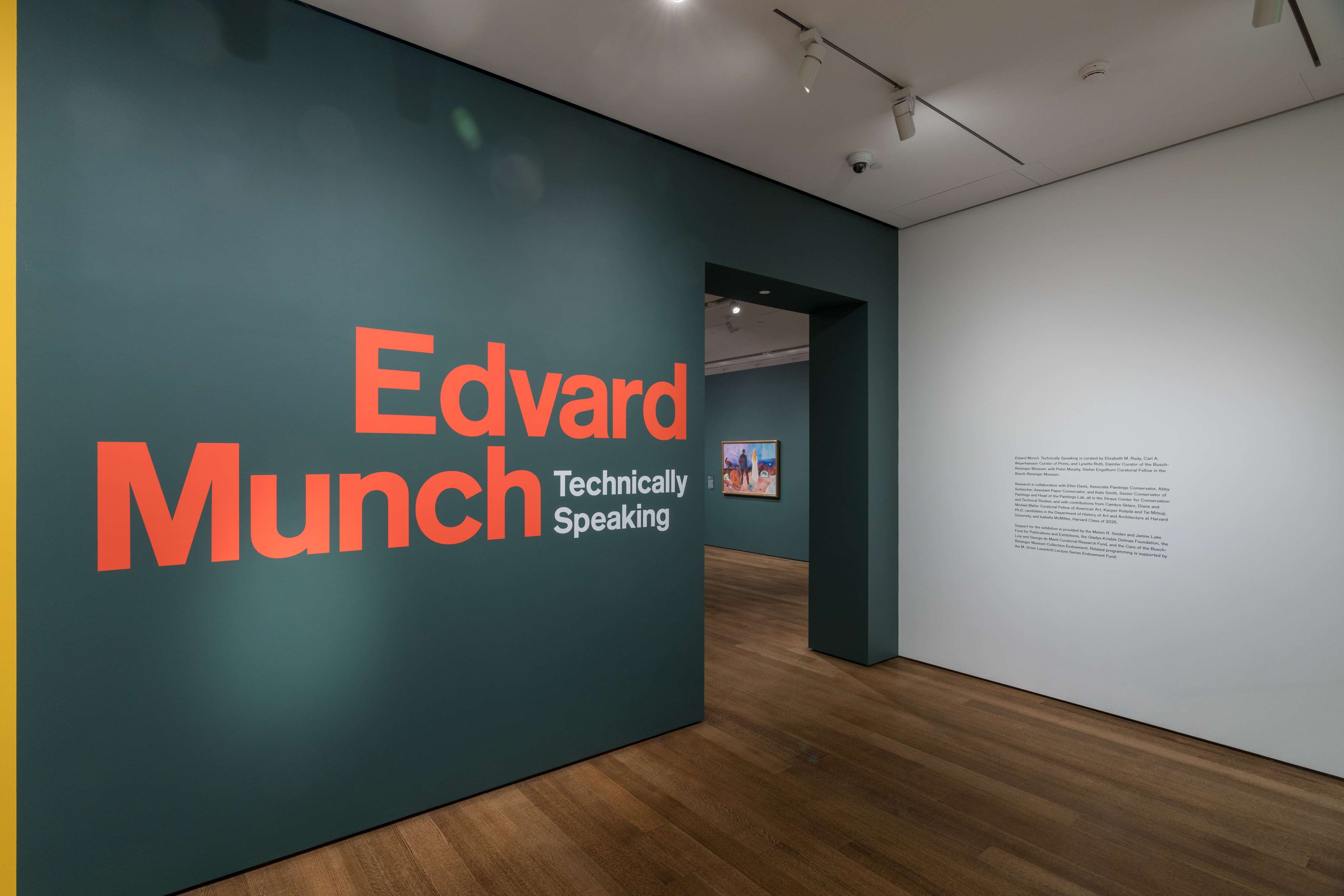

An exhibit at the Harvard Art Museums explores what insights can be gained from Edvard Munch’s four-decade fixation with a man and a woman by the water.

Two individuals, a man and a woman, are positioned at a coastline. They look away from the observer and towards the ocean, standing side by side yet feeling disconnected from one another.

Occasionally, the woman is situated on the left. Other times, she appears on the right. At moments, these figures, together with the rocky coast, are depicted with meticulous brushwork; at other instances, there is perhaps a sense of urgency, of swiftness, or of canvas remaining untouched.

This artwork is “Two Human Beings (The Lonely Ones),” among the most renowned themes by the Norwegian artist and printmaker Edvard Munch (1863-1944). Munch revisited this theme repeatedly over a span exceeding 40 years, in paintings, metalplate etchings, and a series of woodcut prints, each exhibiting subtle variations in hue, form, or technique.

“He couldn’t release it,” remarked Elizabeth M. Rudy, Carl A. Weyerhaeuser Curator of Prints at the Harvard Art Museums and the curator of the exhibition “Edvard Munch: Technically Speaking,” which is on display until July 27. “There are countless more versions of [‘Two Human Beings’] … in monochrome, in grayscale, entirely violet, monochromatic yet with different palettes, completely diverse color combinations. One variant we encountered featured neon colors, transforming the entire work into a psychedelic experience. With the richness of variations, the motif begins to lose its singularity and turns into a medium, an exploration of nearly anything imaginable.”

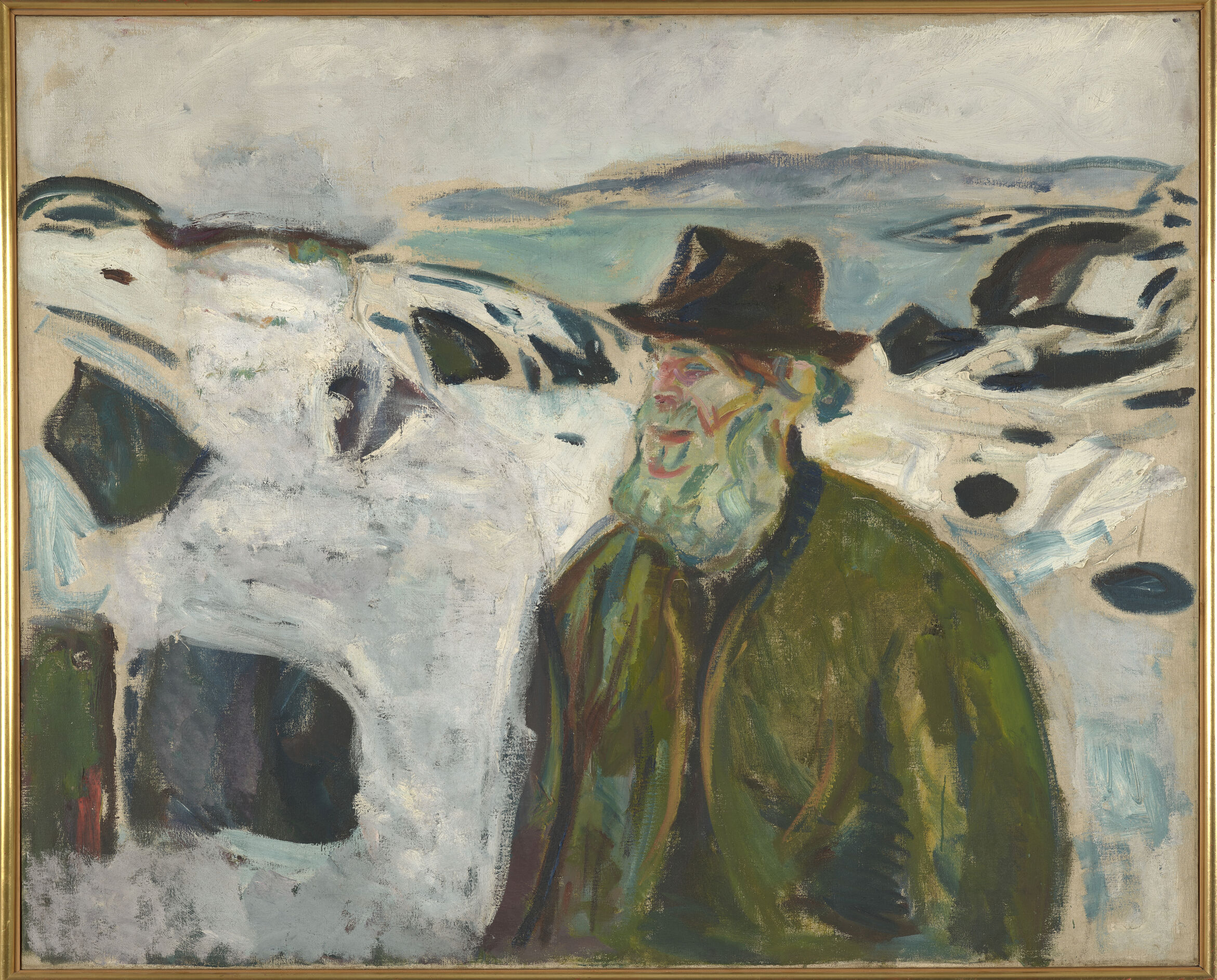

Munch’s persistent exploration of the theme showcases how his paintings influenced his prints, and vice versa. He initially created it in 1892, but the painting was lost in 1901 due to an explosion on a vessel that was transporting his artworks for display. When he revisited the theme around 1906-1908 (above left), he had already delved into woodblock printing of the subject. The figures appear in reverse from the initial painting and were likely derived from the printed copies, which he would have kept as a reference.

“He blends a vast array of distinct painting methods,” stated Lynette Roth, Daimler Curator of the Busch-Reisinger Museum, who co-developed the exhibition. Munch deliberately left portions of the canvas unpainted; in specific areas, he laid paint on thickly or scraped away color. It signifies more than a showcase of skill, Roth asserted: “It also instills a kind of vibration, a feeling of these figures, an energy within the painting itself.”

The final rendition, completed around 1935 (above right), appears more impulsive than its forerunner, displaying visible lines from Munch’s preliminary sketch, large patches of color, and sections of bare canvas.

“It was an aspect we aimed to emphasize,” Roth mentioned. “What fuels this recurrence? What insights is he gaining over time and through various techniques?”

The Lonely Ones, united and disconnected

© Munchmuseet / Richard

Jeffries; © President and Fellows of Harvard College;

courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums

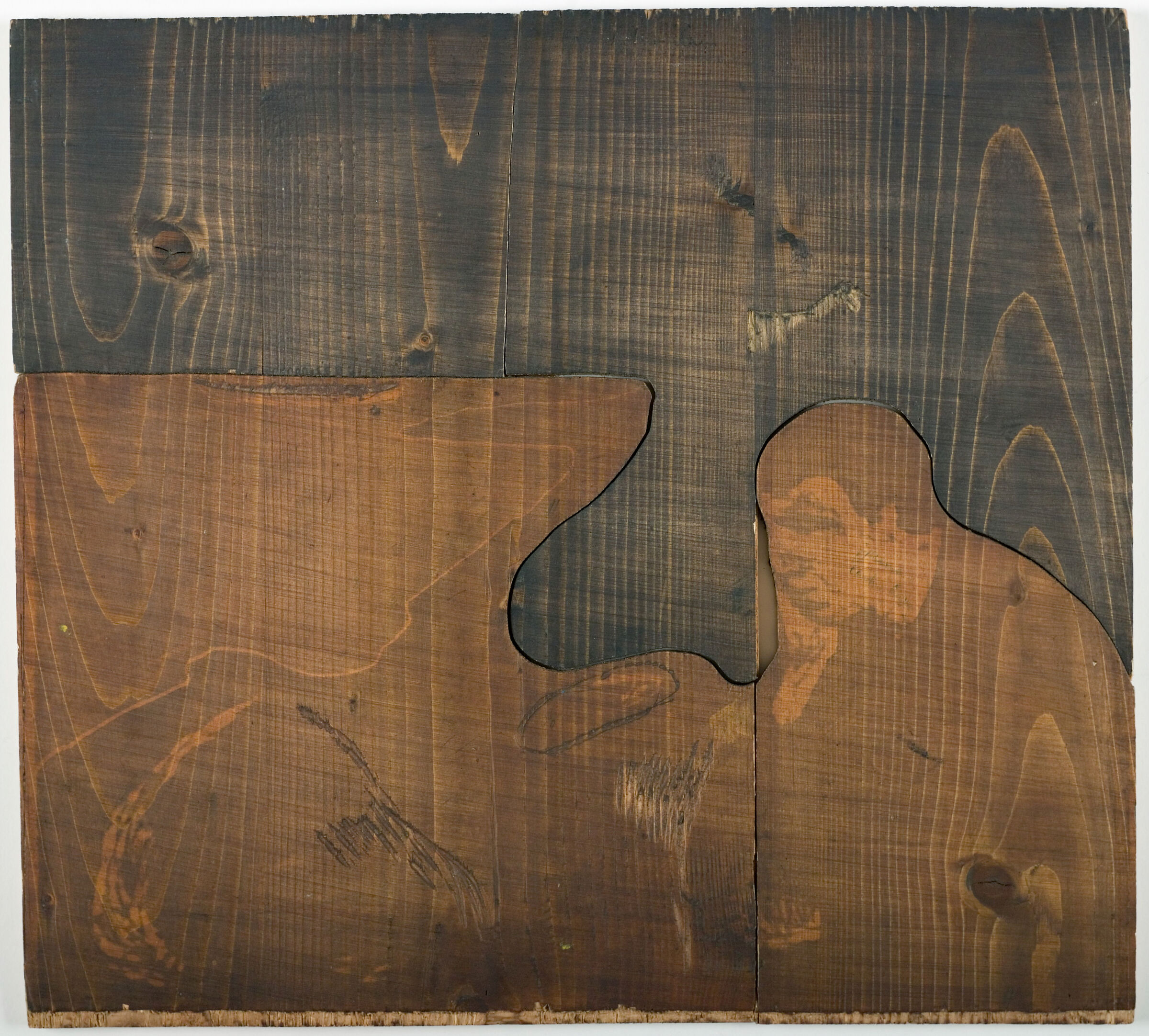

In his prints, Munch deconstructed “Two Human Beings” and reconstructed it anew. He utilized a jigsaw approach, engraving his design onto a wooden block and using a fretsaw to cut each element into individual pieces. Subsequently, he could apply ink to each segment separately, reassemble them, and run the united composition through the press, producing countless variations of hue.

Munch integrated the male figure into the landscape while isolating the woman into her unique solitary block.

“She almost resembles a doll,” Roth noted. “You can separate her out, unlike the man, who becomes intertwined with the printing of the landscape. In many of the prints, he starts to feel more integrated into the scenery, while she remains a distinct and crucial figure for Munch.”

“He welcomed the imperfect alignment, the breaks within the block that would later appear in subsequent prints, the reality that in the painting, aspects are dripping, flaws are visible. That was something he stressed: that an overly polished finish was, in fact, the adversary of true artistry.”

Lynette Roth

“Two Human Beings (The Lonely Ones)” has often been perceived as a reflection on seclusion, on the experience of loneliness even when accompanied by another person. However, after examining Munch’s numerous iterations of the theme, Roth expressed uncertainty that this is the sole reading.

A shrewd businessman, Munch initially named the piece simply “Two Human Beings.” But when others attributed loneliness to the figures, Munch embraced that interpretation.

“The more I delved into this, I began to sense they aren’t necessarily so solitary,” Roth remarked. “They’re connected to the landscape;they are also linked to one another through the manner in which color bonds them, and by the way he is gradually approaching her. … For me, it signifies companionship and reflection, which need not be heartbreaking or isolating, nor a source of unease.”

© President and Fellows of Harvard College; images courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums.

© President and Fellows of Harvard College; images courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums.

© President and Fellows of Harvard College; images courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums.

A query of completionMunch’s peers occasionally criticized a perceived lack of refinement in his creations. However, Munch welcomed the blemishes, irregularities, and voids within his art.

In the final painted rendition of “Two Human Beings,” Munch retains visible sketch marks and patches of unpainted canvas on the woman’s attire.

Edvard Munch, Two Human Beings (The Lonely Ones), 1906–8. Oil on canvas. Harvard Art Museums/Busch-Reisinger Museum, The Philip and Lynn Straus Collection, 2023.551. Photo: © President and Fellows of Harvard College; courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums.

Munch painted over a secondary figure, establishing a visible reminder of an earlier version of “Old Fisherman on Snow-Covered Coast.”

Edvard Munch, Old Fisherman on Snow-Covered Coast, 1910–11. Oil on canvas. Loan from Munchmuseet, Oslo, TL42724.10. Photo: © Munchmuseet / Halvor Bjørngård.

“Inger in a Red Dress” is created on board, an inexpensive medium commonly used by artists for studies. Nonetheless, the artwork is a fully realized portrait.

Edvard Munch, Inger in a Red Dress, 1894. Oil paint, oil pastel, and watercolor on board. Harvard Art Museums/Busch-Reisinger Museum, Gift of Lynn G. Straus in memory of Philip A. Straus, 2012.258. Photo: © President and Fellows of Harvard College; courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums.

“Berlin Model” may seem incomplete, but the surface is coated in casein, a milk-based medium that exhibits a paper-like quality upon drying.

Edvard Munch, Berlin Model, 1895. Oil on canvas. Harvard Art Museums/Busch-Reisinger Museum, Gift of Harry and Patricia Irgens Larsen, 1991.215. Photo: © President and Fellows of Harvard College; courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums.

A flaw can be seen in the woodblock for “Melancholy I.” Munch was recognized for allowing flaws to become part of his compositions.

Edvard Munch, Evening. Melancholy I, 1896. Woodblock (oak). Loan from Munchmuseet, Oslo, TL42724.6. Photo: © Munchmuseet / Richard Jeffries.

A fresh perspective on Munch

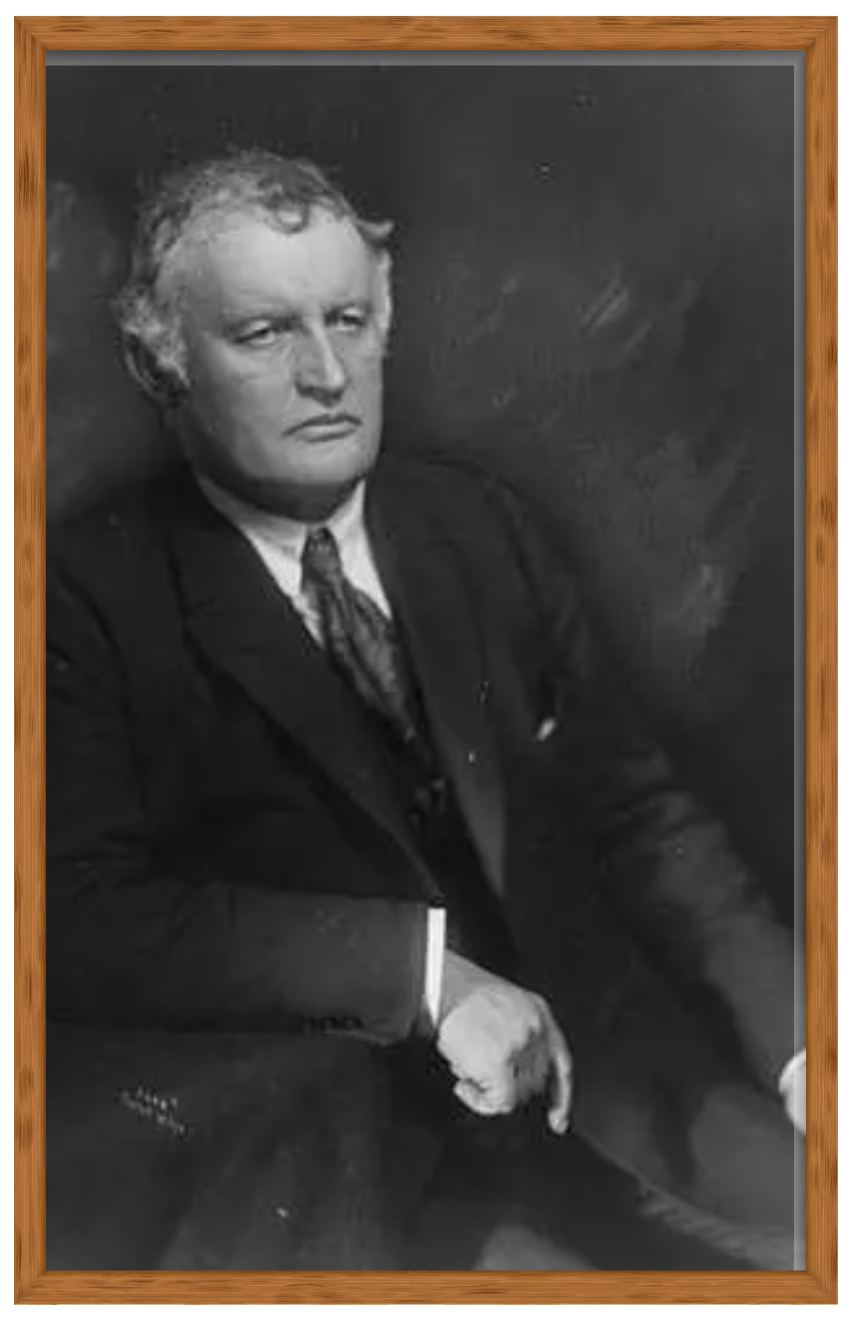

Munch has historically been perceived as a profoundly troubled creator, with his battles with mental well-being evident in psychologically stirring pieces such as “The Scream.” Yet, “Edvard Munch: Technically Speaking” encourages observers to separate Munch’s creations from his personal narrative, enabling them to appreciate his recurring themes not merely as reflections of his mind but as another medium—akin to paint or charcoal—through which Munch examined his artistic journey.

“We understand that viewers will respond emotionally or psychologically to the displayed works,” stated Peter Murphy, the Stefan Engelhorn Curatorial Fellow in the Busch-Reisinger Museum. “Two things can coexist: Munch did experience psychological distress; notwithstanding his affluence and success, he faced numerous crises. However, he was also a genius at disseminating his creations and probing them.”

Edvard Munch

(1863-1944)

Norwegian artist Edvard Munch stands out as one of the most pivotal figures of the Modernist era, pioneering innovative techniques in printmaking, painting, and other artistic disciplines. He is most recognized for his creation “The Scream,” an encapsulation of modern existential anxiety. His career spanned over six decades, from the 1880s until his passing.

“Edvard Munch: Technically Speaking” remains on exhibit until July 27 in the Special Exhibitions Gallery on Level 3 at the Harvard Art Museums. This exhibition features 70 artworks, primarily sourced from the Harvard Art Museums collection. With gratitude to a transformative donation from Philip A. and Lynn G. Straus, the museums now maintain one of the largest and most crucial collections of Munch’s artwork in the United States.