“`html

Science & Technology

‘Transforming data into tangible entities’

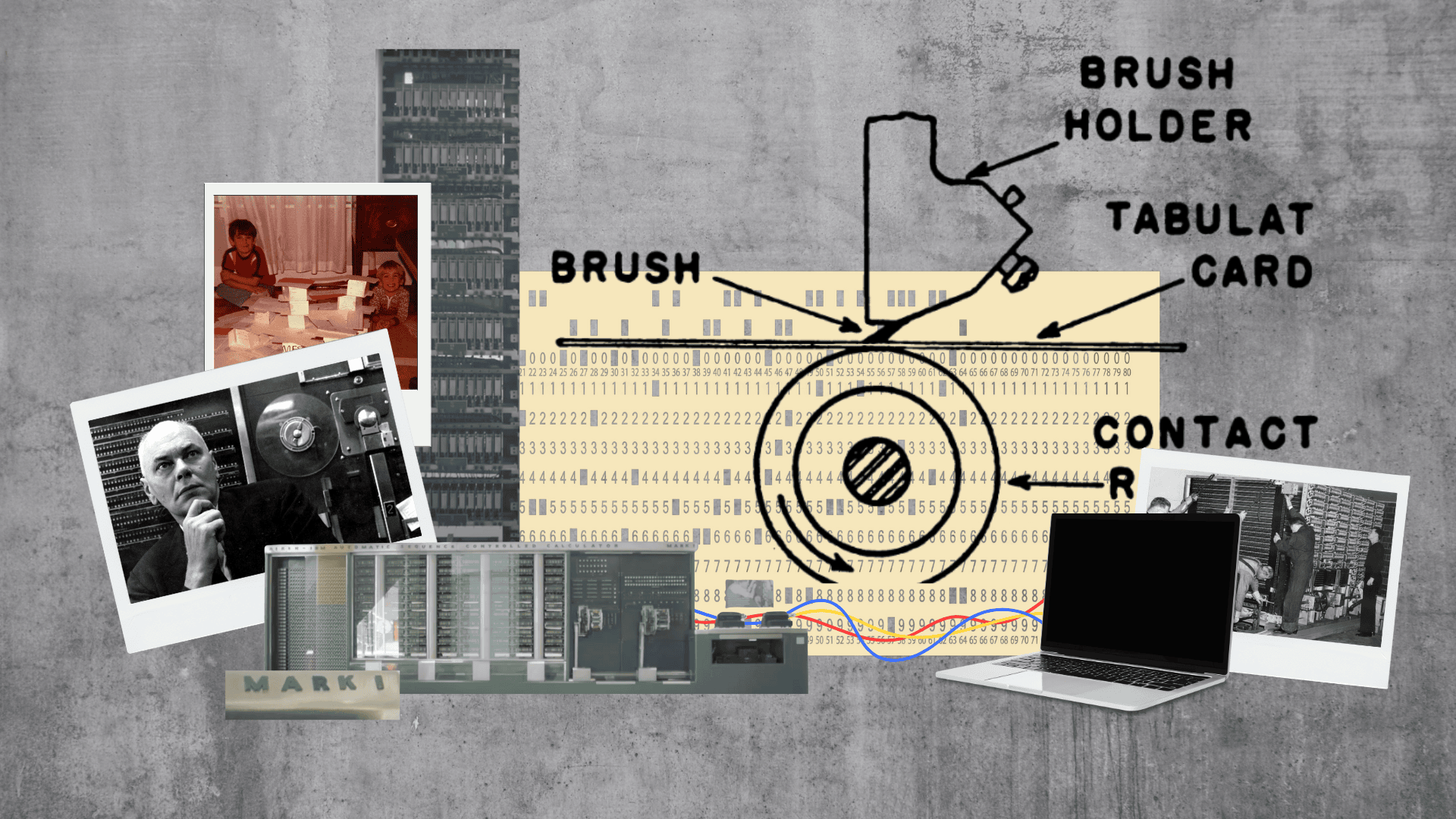

Photo illustration by Liz Zonarich/Harvard Staff

Houghton exhibit explores how punched cards — developed 300 years ago to optimize weaving — contributed to contemporary computing

The punched card, a paper tool conceived 300 years ago to mechanize looms, played a pivotal role in creating a technology that many of us cannot do without today: computers.

A new exhibition at Houghton Library titled “The Punched Card from the Industrial Revolution to the Information Age,” showcased in the library’s lobby until the summer concludes, outlines the evolution of this technology through three significant pieces: a 1886 publication woven entirely with a punched card loom; mathematician Ada Lovelace’s writings on the punched card’s computing potential; and a 1940s guide regarding the operation of a punched card computer.

“Computers are now ingrained in nearly every facet of our society,” remarked the exhibition’s curator, John Overholt. “It’s fascinating to delve into the origins of elements that seem so ubiquitous nowadays … understanding how these aspects developed over time can yield fresh perspectives.”

Punched cards, commonly referred to as punch cards, are believed to have been introduced in 1725, when French silk weaver Basile Bouchon utilized a paper tape with punched openings to automate loom operations. However, a notable early illustration arises from French inventor Joseph Marie Jacquard, who in the early 19th century employed a sequence of punched cards to design elaborate brocade motifs. Each card contained holes aligned to form a single design row.

Historians assert that the initial application of this technology for data collection and analysis took place in the late 1880s, when American engineer Herman Hollerith devised punched cards for gathering statistical data for the U.S. Census.

“That’s the point on which computer historians often debate — where the line should be drawn,” expressed Marc Aidinoff, a technology history instructor at Harvard. “Some argue that programming a loom is fundamentally similar to computing. It’s about inputting instructions.”

Aidinoff emphasized that there is one consensus among technology historians: “There is no computing without punch cards. When one considers what a semiconductor accomplishes, it mirrors the punch card system, merely on a vastly more intricate scale.”

The earliest implementation of punched cards for processing Census data remarkably accelerated the counting of results, marking a critical point in the journey to modern computing. Hollerith’s company — which originated as the Tabulating Machine Company based in Washington, D.C. — eventually evolved into the technology giant IBM.

At Harvard, graduate student Howard Aiken invented the Mark I in 1937 — an unprecedented computer capable of performing a variety of calculations using punched cards.

Aiken collaborated with IBM engineers to develop the machine, and after five years, Mark I was sent to Harvard, where it was utilized by the U.S. Navy Bureau of Ships for defense purposes throughout the subsequent decade.

Punched card computing persisted through the following decades — advancing in tandem with developing microprocessing and memory technologies.

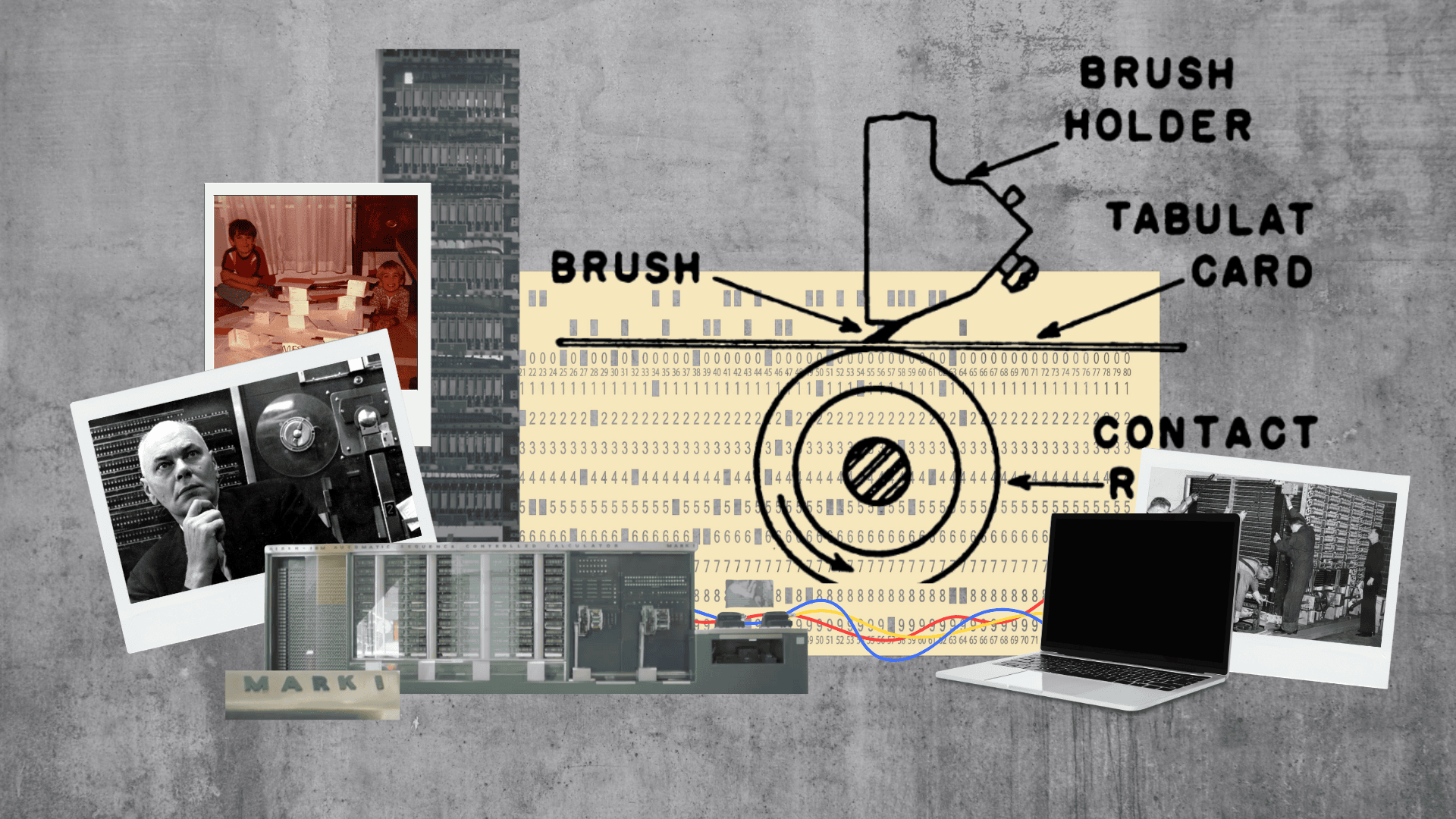

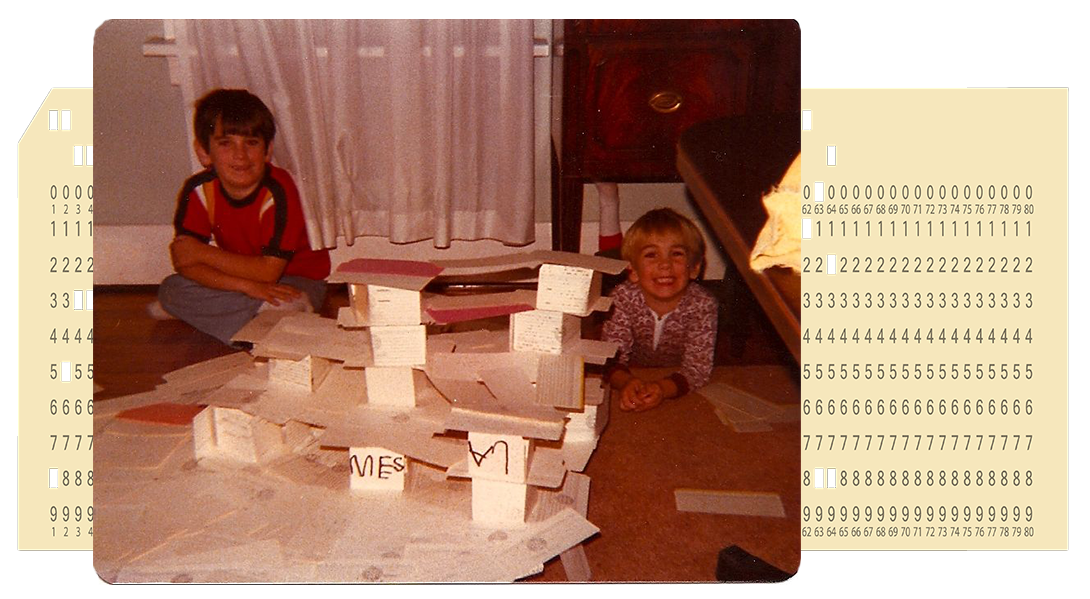

Overholt, curator of Early Books and Manuscripts at Houghton, recalls the discarded punched cards his mother brought home from her position at IBM during the 1960s.

Exhibit curator John Overholt enjoyed playing with the discarded punched cards his mother brought home from her job at IBM during the 1960s.

Photo courtesy of John Overholt

“She would bring back punch cards that had been used for programming computers for us to play with, allowing us to create little card houses,” he reflected.

Today, Harvard is host to supercomputers that render punch card terminals a primitive relic. Yet at Houghton, one can observe the foundational elements of innovation that initiated it all.

“Current computer technology has branched into new territories, but coding in ones and zeros, as well as bits and bytes, remains fundamentally crucial to the operation of computers,” Overholt stated. “I find it challenging to envision what someone 300 years ago might have thought about computers, but it undoubtedly became evident that it was an incredibly potent tool for converting information into a tangible form.”

“The Punched Card from the Industrial Revolution to the Information Age” will be on display in the Houghton Library lobby until the summer’s end. Mark I is currently exhibited in the East Atrium of Harvard’s Science and Engineering Complex in Allston.

“`