According to the narrative, the Scottish creator James Watt conceived how steam engines ought to operate one day in 1765 while strolling through Glasgow Green, a park in his native city. Watt discovered that incorporating a distinct condenser in an engine would enable its primary cylinder to stay warm, rendering the engine both more efficient and streamlined compared to the enormous steam engines of that era.

Nevertheless, Watt, who had been contemplating the challenge for some time, required a collaboration with businessman Matthew Boulton to bring a viable product to the marketplace, which began in 1775 and thrived in subsequent years.

“People still cite Watt’s ‘Eureka!’ tale, which Watt himself promoted later in life,” remarks MIT Professor David Mindell, an engineer and scholar of science and engineering history. “However, it necessitated 20 years of relentless effort, during which Watt grappled with supporting a family and faced numerous setbacks, to introduce it to the public. Various other inventions were essential to reach what we currently refer to as product-market fit.”

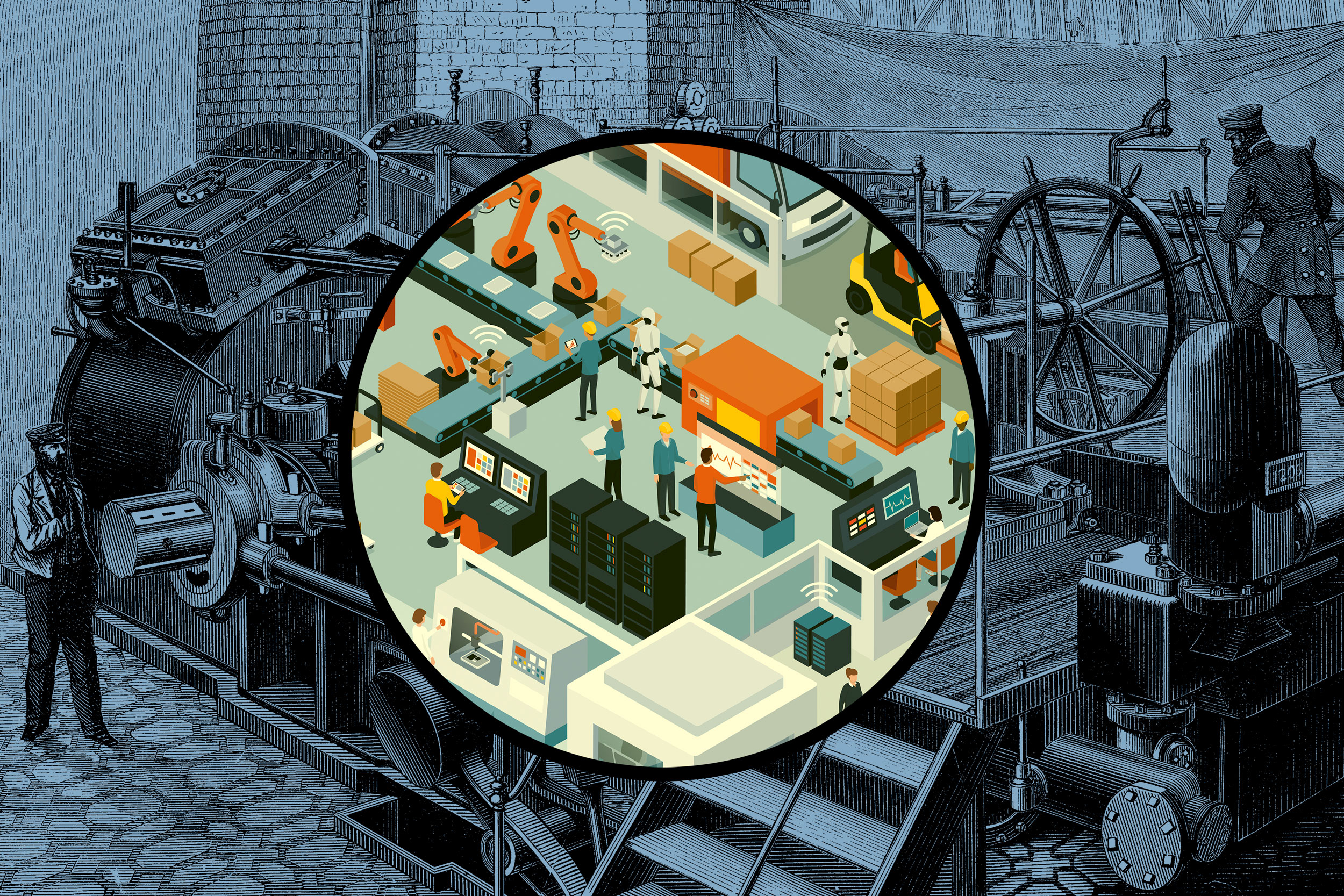

The comprehensive narrative of the steam engine, Mindell contends, exemplifies a classic instance of what is currently termed “process innovation,” as opposed to merely “product innovation.” Innovations are seldom fully-developed products, ready to transform the world. They typically require a series of enhancements and continued advocacy to be integrated into industrial frameworks.

What was applicable for Watt still remains true today, as evidenced by Mindell’s extensive research. Most technology-driven advancement nowadays arises from overlapping progressions, as inventors and companies adjust and enhance existing solutions over time. Mindell is currently delving into these themes in an upcoming publication, “The New Lunar Society: An Enlightenment Guide to the Next Industrial Revolution,” set to debut on Feb. 24 from the MIT Press. Mindell is a professor of aeronautics and astronautics and the Dibner Professor of the History of Engineering and Manufacturing at MIT, where he has also co-established the Work of the Future initiative.

“We’ve placed too much emphasis on product innovation, although we excel at it,” Mindell states. “However, it has become evident that process innovation holds equal importance: the methods by which we enhance the creation, repair, rebuilding, or upgrade of systems. These elements are deeply interwoven. Manufacturing is an integral aspect of process innovation.”

In an age where numerous items are showcased as transformative products, it may be particularly crucial to acknowledge that adaptability and perseverance are essentially the heart of enhancement.

“Young innovators often don’t recognize that when their creation fails initially, they are at the onset of a journey where they must refine, engage, and identify the right collaborators to expand,” Mindell observes.

Manufacturing at Home

The title of Mindell’s book references British Enlightenment thinkers and creators — Watt was among them — who regularly convened in a collective known as the Lunar Society, based in Birmingham. This group included pottery innovator Josiah Wedgwood; physician Erasmus Darwin; chemist Joseph Priestley; and Boulton, a metal manufacturer whose labor and capital were pivotal in transforming Watt’s enhanced steam engine into a dependable product. The book alternates between chapters covering the historical Lunar Society and those discussing modern industrial systems, highlighting parallels between past and present.

“The narratives surrounding the Lunar Society serve as models for how individuals can navigate their careers, whether in engineering or other fields, in ways that may not be evident in the mainstream discourse about technology today,” Mindell remarks. “Many claimed Wedgwood could not stand up to Chinese porcelain; nevertheless, he learned from the Lunar Society and constructed an English pottery sector that led globally.”

Applying the principles of the Lunar Society to present-day industry leads Mindell to a fundamental collection of ideas regarding technology. Research indicates that design and manufacturing should coexist whenever feasible, rather than being outsourced internationally, to expedite learning and cooperation. The book further posits that technology should meet human requirements and that venture capital should direct more attention to industrial systems. (Mindell has co-founded a venture, called Unless, that invests in companies utilizing financing models better suited for industrial transformation.)

In witnessing a new form of industrialism emerging, Mindell proposes that its future encompasses novel ways of working, collaborating, and valuing knowledge throughout organizations, along with increased AI-based open-source tools for small and medium-sized manufacturers. He also argues that a new industrialism should place a heightened focus on maintenance and repair work, which serve as significant reservoirs of knowledge regarding industrial devices and systems.

“We’ve undervalued the importance of keeping things operational, while simultaneously eroding the middle tier of the workforce,” he states. “Yet, operations and maintenance are critical sites of product innovation. Inquire with the individual who repairs your vehicle or dishwasher; they will inform you of the strengths and weaknesses of every model.”

In summary, “The cumulative nature of this work, over time, constitutes a new industrialism if it elevates its cultural significance into a movement that appreciates the material foundation of our lives and strives to enhance it, literally from the ground up,” Mindell asserts in the book.

“The publication doesn’t forecast the future,” he clarifies. “Instead, it proposes ways to discuss the future of industry with both optimism and realism, rather than asserting, this is the utopian future where machines perform all tasks, and individuals merely recline in chairs with wires extending from their heads.”

Work of the Future

“The New Lunar Society” is a succinct work filled with expansive concepts. Mindell also dedicates chapters to the intersection of the Industrial-era Enlightenment, the establishment of the U.S., and the essential role of industry in shaping the republic.

“The sole founding father who signed all pivotal documents at the nation’s inception, Benjamin Franklin, was also the individual who crystallized the modern science of electricity and implemented its first practical invention, the lightning rod,” Mindell explains. “However, there were several key figures, including Thomas Jefferson and Paul Revere, who integrated the industrial Enlightenment with democracy. Industry has been integral to American democracy from its inception.”

Indeed, as Mindell underscores in the book, “industry,” beyond recalling smokestacks, carries a human implication: When you demonstrate diligence, you exhibit industry. This aligns with the concept of continuously refining an invention over time.

Despite the high esteem in which Mindell regards the Industrial Enlightenment, he acknowledges that the period’s industrialization led to severe working conditions and environmental harm. As one of the co-founders of MIT’s Work of the Future initiative, he advocates that 21st-century industrialism must reassess some of its core principles.

“The principles of [British] industrialization neglected environmental concerns and labor rights,” Mindell emphasizes. “So at this juncture, how do we reevaluate industrial systems to improve outcomes?” Mindell contends that industry should fuel an economy that expands while also decarbonizing.

Ultimately, Mindell notes, “Approximately 70 percent of greenhouse gas emissions originate from industrial sectors, and all potential solutions necessitate the creation of numerous new items. Even if it’s merely connectors and wires. We will not achieve decarbonization or tackle global supply chain crises by deindustrializing; we will reach our goals by reindustrializing.”

“The New Lunar Society” has garnered accolades from technologists and various scholars. Joel Mokyr, an economic historian at Northwestern University who introduced the term “Industrial Enlightenment,” has remarked that Mindell “recognizes that innovation necessitates a combination of knowledge and craftsmanship, mind and hand. … He has produced a profoundly original and insightful work.” Jeff Wilke SM ’93, a former CEO of Amazon’s consumer division, has stated that the book “compellingly argues that a flourishing industrial foundation, skilled in both product and process innovation, supports a robust democracy.”

Mindell aspires for the book to appeal to a diverse audience, from emerging technologists to a wider readership interested in the future of industry.

“I consider the younger generation in industrial environments and wish to help them recognize that they are part of a magnificent legacy and are accomplishing significant work to alter the world,” Mindell expresses. “There exists a vast audience of individuals intrigued by technology but who find exaggerated rhetoric that doesn’t align with their hopes or personal experiences. I’m endeavoring to crystallize this new industrialism as a framework for envisioning and discussing the future.”