“`html

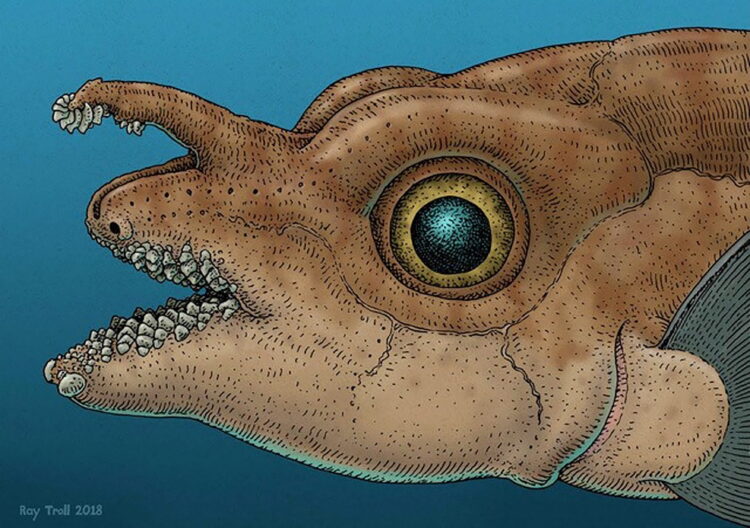

A research team led by the University of Washington discovered teeth on the tenaculum of adult male spotted ratfish. They unearthed indications of a similar formation in fossils from ancient ratfish relatives, reimagined here by local artist Ray Troll.Ray Troll

When discussing teeth, vertebrates exhibit many similarities. Regardless of shape, size, or sharpness, teeth possess genetic origins, physical attributes, and, of course, reside in the jaw.

Recent discoveries challenge one of these fundamental beliefs. Spotted ratfish, a shark-like species indigenous to the northeastern Pacific Ocean, feature rows of teeth atop their heads, lining a cartilaginous structure known as the tenaculum, which loosely resembles Squidward’s snout.

Scientists have long pondered the origins of teeth—structures so crucial for survival and evolution that few of us take a moment to reflect on them. However, the discussion has primarily focused on the evolution of dental teeth, without exploring the idea that teeth could exist in other locations. The discovery of teeth on the tenaculum prompts researchers to consider where else they might be present, and how this might reshape our understanding of dental history.

“This incredible, truly remarkable feature overturns the long-held belief in evolutionary biology that teeth are solely oral structures,” remarked Karly Cohen, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Washington’s Friday Harbor Labs. “The tenaculum is a developmental remnant, not just an oddity, and the first clear indication of a toothed structure beyond the jaw.”

The findings were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on September 4.

Spotted ratfish rank among the most prevalent fish species in Puget Sound. They belong to a class of cartilaginous fish known as chimaeras, which diverged from sharks on the evolutionary tree millions of years ago. Measuring around 2 feet in length, spotted ratfish are named for their long slinky tails that make up half of their body length. Only adult males possess a tenaculum that adorns their foreheads. At rest, it resembles a small white peanut between their eyes, but when raised, the tenaculum is hooked and studded with teeth.

Males extend their tenaculum to intimidate rivals, and during mating, they grasp females by the pectoral fin to prevent drifting apart.

“Sharks lack arms, yet they need to mate underwater,” Cohen noted. “Thus, many have evolved gripping structures to hold onto a partner during reproduction.”

Spotted ratfish also possess pelvic claspers for this purpose.

Many common sharks, rays, and skates are covered in tooth-like formations called denticles. Aside from the denticles on their pelvic claspers, spotted ratfish are “rather bare,” Cohen remarked, leading the researchers to ask: Where have all their denticles gone?

Prior to this investigation, two theories existed. One suggested that the “teeth” on their tenaculum were remnants of vestigial denticles from the past. The other proposed that they were true teeth, akin to those found in the oral cavity.

“Ratfish possess quite unusual faces,” Cohen said. “When small, they somewhat resemble an elephant squished into a tiny yolk sack.”

The cells responsible for forming the oral region are more widely distributed, making it feasible that at some point, a collection of tooth-forming cells may have migrated to the head and adhered.

To validate these theories, the researchers captured and examined hundreds of fish, utilizing micro-CT scans and tissue samples to document the development of the tenaculum. While studying sharks can be quite challenging, spotted ratfish are plentiful in Puget Sound. They inhabit the shallow waters around Friday Harbor Labs, the UW research center located on San Juan Island. They also contrasted the modern ratfish to ancient fossils.

The scans indicated that both male and female ratfish begin developing a tenaculum early on. In males, it evolves from a minor cluster of cells into a tiny white bump that elongates between the eyes. It connects to muscles controlling the jaw and finally breaks through the skin’s surface, sprouting teeth. In females, it never fully develops—or mineralizes—but signs of an early structure persist.

The new teeth are anchored in a tissue band called the dental lamina, which exists in the jaw but has not been documented elsewhere. “When we observed the dental lamina for the first time, we were astonished,” Cohen stated. “It was exhilarating to witness this critical structure outside the jaw.”

In humans, the dental lamina deteriorates after we develop our adult teeth, but many vertebrates retain the capacity to regenerate teeth. Sharks, for instance, have “a continuous conveyor belt” of new teeth, Cohen explained. Dermal denticles, including those on the pelvic claspers of the spotted ratfish, do not possess a dental lamina. Identifying this structure provided compelling confirmation that the teeth on the tenaculum are genuine teeth rather than remnants of denticles. Genetic evidence further supported this conclusion.

“Vertebrate teeth are exceptionally well linked by a genetic toolkit,” Cohen remarked.

Tissue samples revealed that the genes associated with teeth across vertebrates were active in the tenaculum, but not in the denticles. In the fossil record, they also found indications of teeth on the tenaculum of related species.

Upper: An adult male spotted ratfish photographed near Friday Harbor Labs. The tenaculum is visible to the left of its eye. Lower: The shape and anatomy of the fish, captured by micro-CT scan. This technology reveals morphological features, including the tenaculum, in striking detail.University of Washington

“We have a synthesis of experimental data and paleontological evidence to illustrate how these fish repurposed a preexisting program for generating teeth to create a novel device that is crucial for reproduction,” explained Michael Coates, a professor and chair of organismal biology and anatomy at the University of Chicago and a co-author of the study.

The contemporary adult male spotted ratfish can

“““html

develop seven or eight rows of hooked fangs on its tenaculum. These fangs retract and bend more than the typical canine, allowing the fish to grip onto a partner while swimming. The dimensions of the tenaculum also seem to have no connection to the size of the fish. Its growth correlates instead with the pelvic claspers, indicating that the migratory tissue is now governed by different systems.

“If these peculiar chimaeras are attaching fangs to the front of their head, it certainly prompts thoughts about the variability of tooth formation more broadly,” stated Gareth Fraser, a biology professor at the University of Florida and the primary author of the study.

Sharks are frequently utilized as a model for examining teeth and their development due to their abundance of oral teeth and their coverage of denticles. However, Cohen noted that sharks represent only a fragment of the dental diversity captured through time. “Chimeras provide a unique insight into the past,” she remarked. “I believe that the more we investigate spiky formations on vertebrates, the more teeth we will discover outside the jaw.”

This investigation received funding from the National Science Foundation, the Save Our Seas Foundation, and internal grants at Friday Harbor Labs aimed at fostering pioneering early-career research.

For additional details, reach out to Karly Cohen at [email protected].

“`