The beginning of the Revolutionary War, occurring 250 years ago, can be linked to a single document that detailed the orders for the Concord Expedition on April 18, 1775.

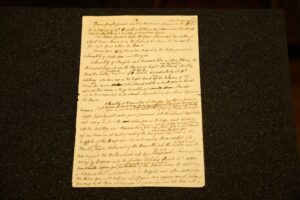

The tangible quill-to-paper draft directives penned by the renowned British Army officer Thomas Gage, which ignited the battles of Lexington and Concord, are preserved at the University of Michigan Clements Library.

Characteristic of the era, the draft incorporated Gage’s initial handwritten reflections based on intelligence gathered from his agents, while the eventual document sent out would be written by his secretary, with an additional secretarial copy kept for their archives, which also forms part of the Clements’ collection.

Maj. Gen. Gage, who was the commander-in-chief of British forces in North America during the decade preceding the American Revolution and governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay from 1774 to 1775, dispatched the following orders to Lt. Col. Francis Smith:

“Sir, You are to proceed with the Corps of Grenadiers and

Light Infantry placed under your Command with utmost Expedition

and confidentiality to Concord, where you will confiscate and eliminate

all Artillery and Ammunition Provisions Tents & all other military supplies you can discover, you shall remove at least one Trunion from each of the Iron Guns, and ruin the Carriages and crush the Muzzles of the Brass ones so as to make them inoperative.”

Smith guided the soldiers across the Charles River to the mainland and activated the American rebels’ prearranged communication system—including alarm riders Paul Revere, William Dawes, and Samuel Prescott—to alert the countryside. Throughout April 19, as they proceeded northward, British forces faced armed opposition from American Minutemen at Lexington, igniting the first shots of the Revolution on April 19, 1775.

“One can observe in the draft document where Gage has made additions, where he has crossed out parts of his preliminary thoughts. You will also find lists of notes regarding specific locations where he surmised that military supplies, ammunition, provisions, tents are located in Concord. It illustrates how Gage’s ideas evolved within this context, and later took shape in their final concrete version,” remarked Cheney Schopieray, the curator of manuscripts at the Clements and project director.

“One notable distinction between the draft and the final version is that the draft lacks the phrase, ‘but you will ensure that the soldiers do not pillage the inhabitants or damage private property.’ That sentence was included sometime between the draft and the final document being sent out.”

The Gage letter is a component of the Thomas Gage Papers compilation, which consists of over 23,000 items. This is among the largest and most frequently accessed collections at the Clements, where researchers can find handwritten letters, documents, diaries, financial statements, military orders, and more.

Due to a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the entire Thomas Gage Papers have been digitized; 50 volumes are openly available online now, with intentions to make the remaining materials accessible later this year.

“The Gage papers, considered one of the essential treasures of the Clements Library, have been examined by countless generations of historians,” Schopieray pointed out. “They provide remarkable documentation of colonial America through the paperwork of the highest levels of British governance in the colonies during the turbulent years leading up to the Revolutionary War.”

Acquired in 1930 by William L. Clements, the eponymous figure of the historical library, the collection was delivered in a dozen secretarial trunks, one for each year of Gage’s command over the British military in North America.

“Most of the trunks consisted of two levels of pigeon holes, each of which—these rectangular compartments for storing documents—were labeled with either a geographic location or city, or military station,” Schopieray explained.

“When correspondence or documents were received by the commanding officer, they would read them, assimilate the information, decide whether and how to respond, and file them accordingly. This allowed them to track what the communication entailed and ascertain if any referenced letters were missing.”

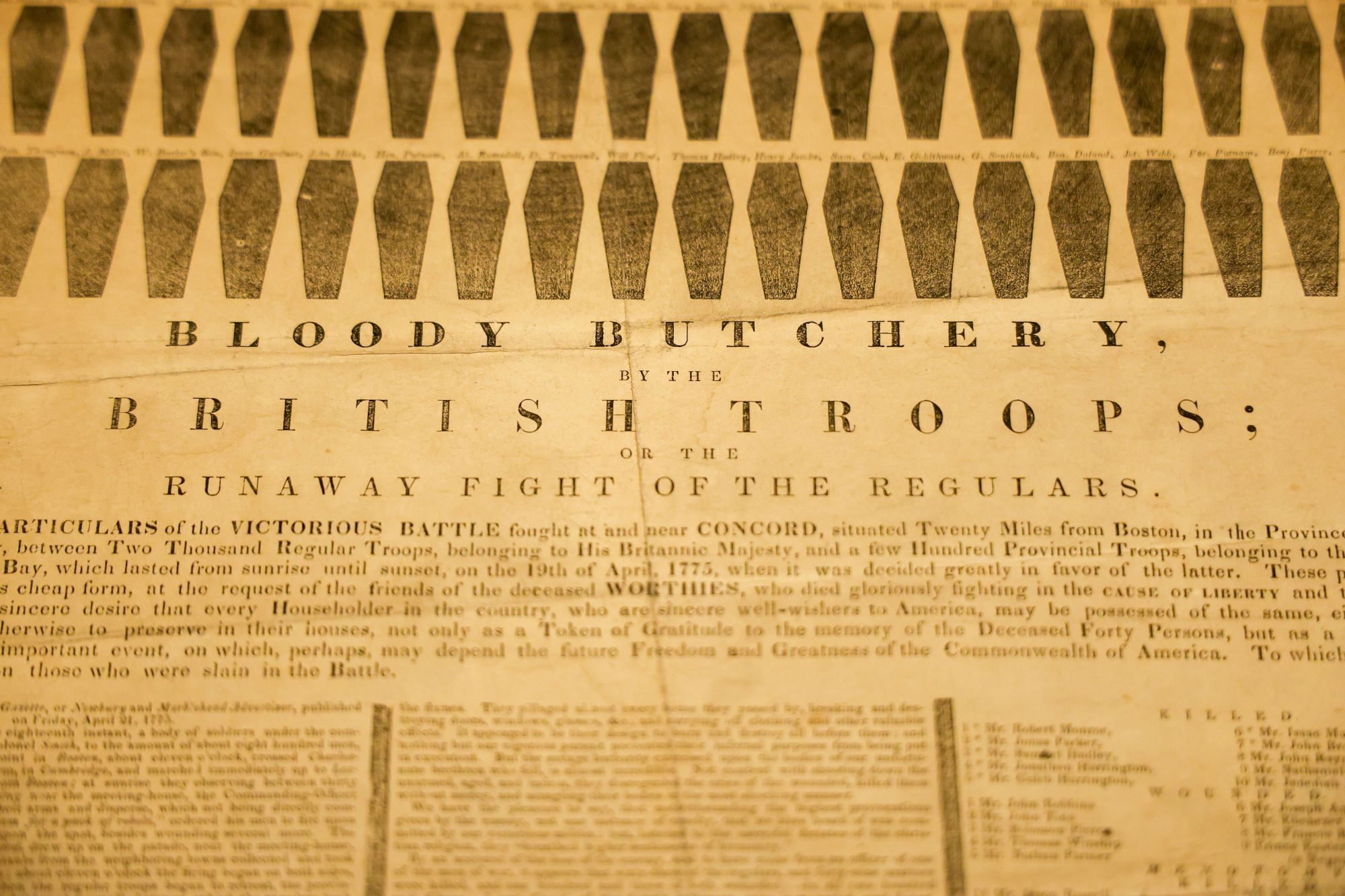

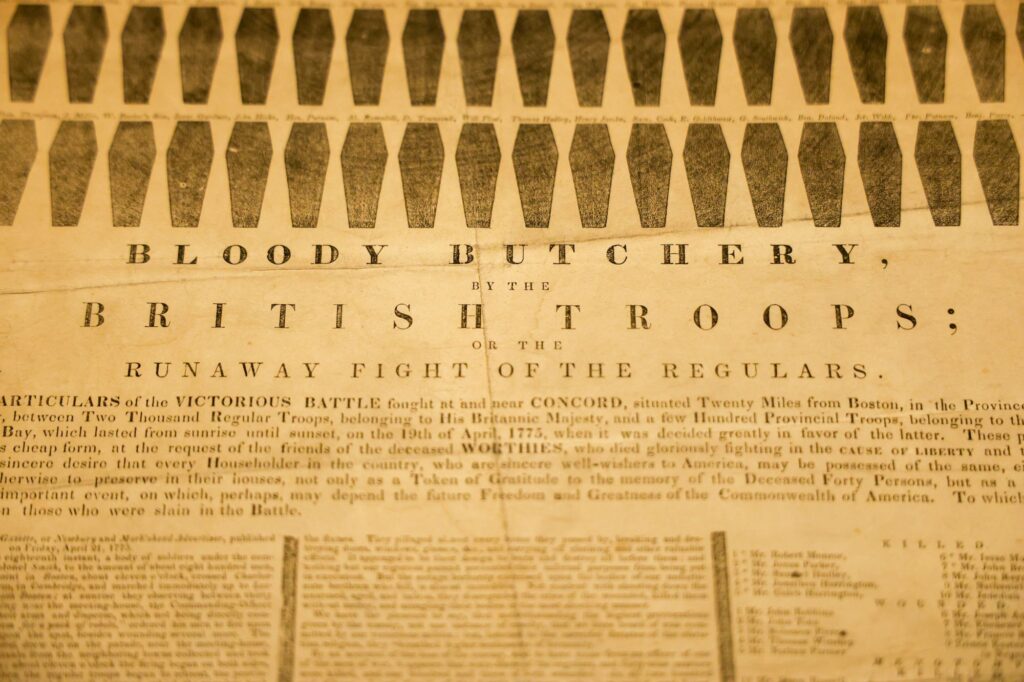

Items from the collection—such as one of the aforementioned secretarial trunks, authentic historical manuscript letters, documents, periodicals, and artwork—will also be exhibited as part of the library’s newest showcase, “Bloody Work: Lexington and Concord 1775.”

“What I’m primarily highlighting in the exhibit is the time just prior to the orders being issued to Francis Smith of the Tenth Regiment of Foot on April 18 of 1775, commanding him to advance northwest from Boston to capture military supplies at Concord, the implications of this command as it was executed on April 19, and the immediate consequences that followed,” Schopieray stated.

Given that these materials can be challenging to interpret and are filled with abbreviations, the Clements sought the assistance of students from the U-M School of Music, Theatre & Dance, who are studying voiceover and acting, to narrate each of the manuscripts featured in the exhibit.

One such correspondence is a message from Rachel Revere to her spouse Paul, which was intercepted by British agents and handed to Gage. This is the reason it is included in the collection today; it never reached its intended addressee.

“Handwritten letters and documents are essential for comprehending not just the events of the past, but also for linking these resources to the individuals who produced them,” Schopieray articulated.

“For instance, when examining this draft letter, you can observe Thomas Gage’s handwriting. You can see where he applied more pressure with the pen, or what he chose to emphasize, including areas where he pressed too hard, resulting in minor ink splatters. It brings you as close as possible to the physical person composing the documents, and that is an immensely powerful experience.”

He contends that the tangible characteristics of manuscripts render them quite intimate and enhance the connection to the humanity of those who experienced these pivotal moments in history.

“Bloody Work” is free and accessible to the public, available until September 19, 2025.