Arts & Culture

‘The Odyssey’ is experiencing a resurgence. Once more.

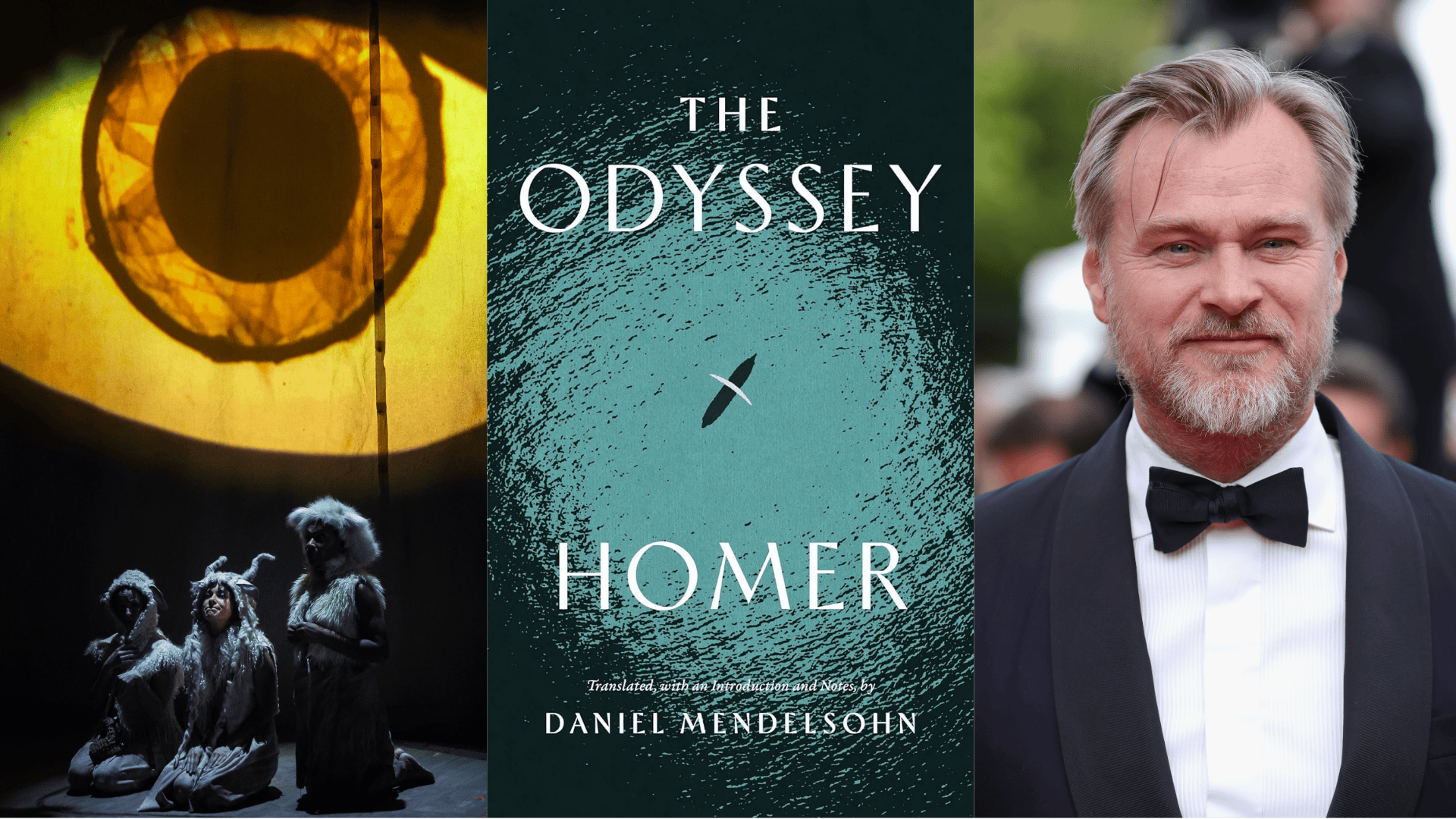

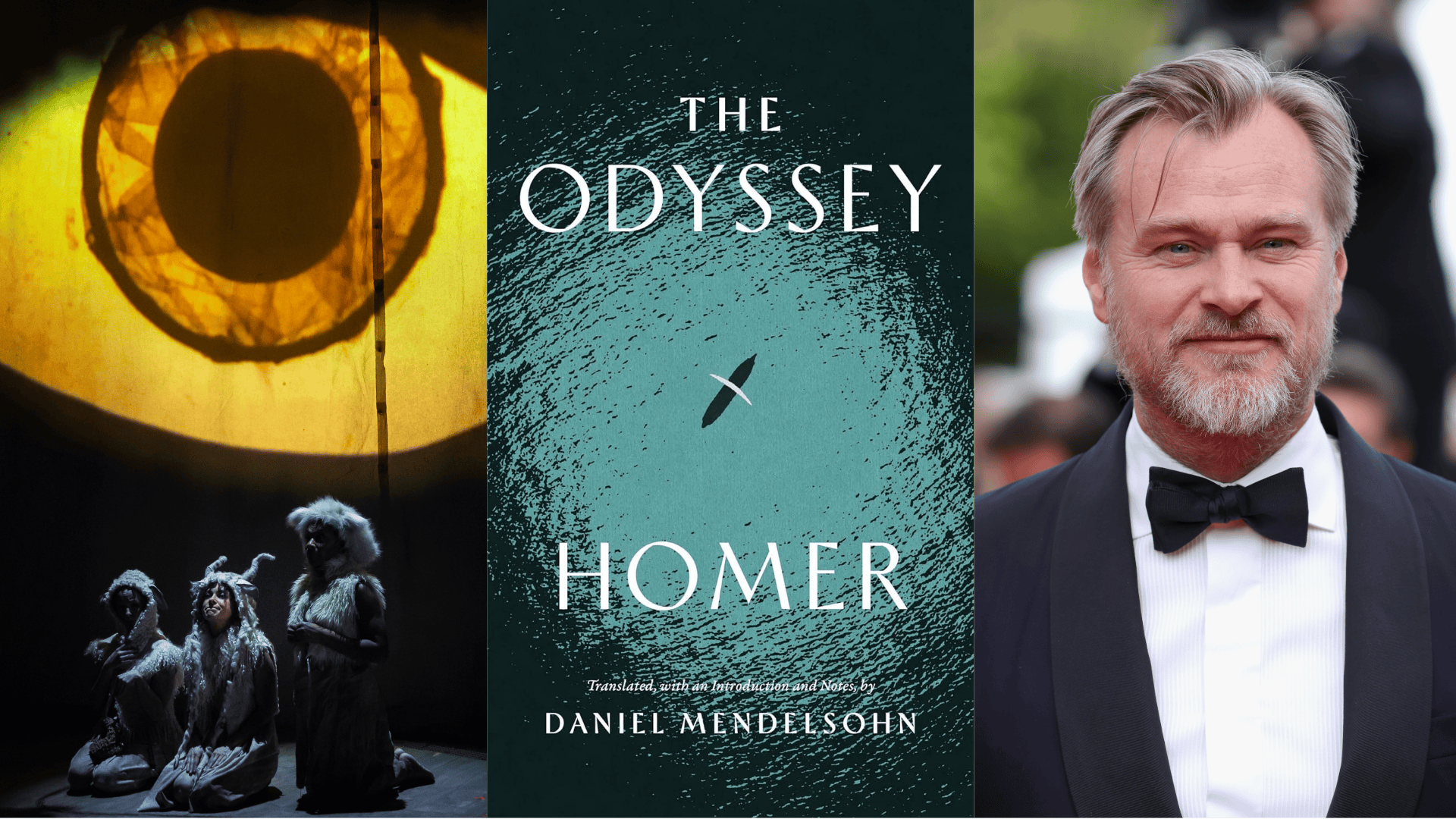

The lasting attraction of “The Odyssey” is exemplified in the A.R.T.’s staging; a new rendition by Daniel Mendelsohn; and an upcoming film from director Christopher Nolan (illustrated).

Images by Nile Scott Studio and Maggie Hall; Andreas Rentz/Getty Images

Classicist Greg Nagy discusses the epic’s allure, his preferred translation, and the ‘soul’s journey’ that awaits new audiences

The epic tale of Homer’s “The Odyssey” has captivated audiences for almost 3,000 years. Proof of its lasting allure is abundant: A theatrical adaptation of the poem is running through Sunday at the American Repertory Theater; a film directed by Academy Award-winning filmmaker Christopher Nolan is in development; and a new version by scholar Daniel Mendelsohn is set to be released next month.

In this modified dialogue, Greg Nagy, the Francis Jones Professor of Classical Greek Literature and Professor of Comparative Literature, shares his favorite among the myriad translations of this poem, discusses the charm of the “trickster” Odysseus, and more.

Can you share insights about Homer?

There are no historical details concerning the individual known as Homer. Nonetheless, the historical context surrounding how listeners of Homeric poetry perceived the poet is significant. The evolution of Homeric poetry occurred in two distinctive phases. The first phase unfolded in coastal Asia Minor, now part of modern-day Turkey, and in surrounding islands belonging to present-day Greece. During the late eighth and early seventh centuries B.C.E., a coalition of 12 Greek Ionian cities formed here, shaping “The Iliad” and “The Odyssey” into their recognizable structure. The second phase transpired in pre-classical and classical Athens, around the sixth and fifth centuries B.C.E. Prior to this latter phase, nearly any epic text could be linked to this mythologized persona known as Homer.

“There are no historical details concerning the individual known as Homer. Nonetheless, the historical context surrounding how listeners of Homeric poetry perceived the poet is significant.”

With over 100 translations of the poem available, do you have a personal favorite?

I admire the rendition by George Chapman, a poet himself, who produced the first complete English translation of “The Odyssey” in 1616. There is that renowned poem by John Keats (1816), where he reflects on reading Chapman’s version of Homer. I am also fond of the translation by Emily Wilson, who became the first female translator of “The Odyssey” (2017) into English.

Additionally, I appreciate the translations by Richmond Lattimore and Robert Fitzgerald, both of whom were close companions. Lattimore was likely one of the most precise translators of Homeric poetry; he was devoted to the original Greek text as it was eventually recorded. His text is visually appealing, though it can be challenging to recite. Fitzgerald’s version is more pleasing to the ear. Then there’s Robert Fagles (1996), who produced the most performance-friendly translation.

I hold Wilson’s translation in high regard. She is an exceptional poet; she possesses a keen sensitivity to the thoughts and emotions of the characters. One aspect I particularly enjoy is how Wilson portrays the brutal demise of the disloyal handmaidens to Odysseus, treating their agonizing end with remarkable nuance devoid of any insincere pity.

Novelist Samuel Butler, a true romantic of the Victorian era, authored “The Authoress of ‘The Odyssey,’” positing that the poem was not crafted by Homer, but by his daughter. For her remarkable translation, I would argue that Wilson could be viewed as Homer’s daughter.

What draws us to Odysseus? His cleverness, vengefulness, and numerous flaws …

During my time as a graduate student at Harvard, I learned from my professor, John H. Finley, that Odysseus, typically viewed as an epic hero, receives “bad press” almost universally, with the exception of “The Odyssey.” Odysseus exemplifies what anthropologists classify as a trickster—a hero who does not initially fit the epic hero mold but, through comprehensive knowledge of societal norms, can break every rule, whether it be a deeply entrenched moral code or subtle etiquette, as seen with dining manners. The worth of the trickster lies in this: it elucidates what the rules are, as the trickster reveals how each one can be subverted.

“The worth of the trickster lies in this: it elucidates what the rules are, as the trickster reveals how each one can be subverted.”

The opening line of “The Odyssey” encapsulates it well: “The man, sing him to me, O Muse, that man of twists and turns …” What could be more captivating than an individual with an infinite ability to transform identities?

Who is your preferred character? Odysseus? Penelope? Telemachus?

My preferred character in “The Odyssey” is Penelope due to her intelligence. I have written a commentary analyzing the dream Penelope recounts to her disguised husband. If my interpretation holds true, her skillful narration suggests that she possesses even greater intellect than Odysseus!

Ultimately, what should readers take away from the poem?

In the Homeric “Odyssey,” the protagonist undergoes a “soul’s journey.” Engaging with the epic can facilitate the reader’s own voyage.