Numerous factors contribute to Haiti’s contemporary issues. A valuable insight into these challenges can be gained by revisiting around 1715 and engaging with a complex tale involving the French crown, a financial gambler named John Law, and a stock-market failure known as the “Mississippi Bubble.”

In brief: Following the passing of Louis XIV in 1715, France found itself entrenched in debt after years of conflict. The nation momentarily ceded its economic strategy to Law, a Scotsman who instituted a framework where, among other things, French debt was alleviated while private monopolistic firms expanded international trade.

This initiative did not unfold entirely as intended. Speculation in the stock market resulted in the “Mississippi Bubble” and the subsequent crash of 1719-20. Amid the turmoil, Law suffered a fleeting fortune and departed from France.

Nonetheless, Law’s framework had enduring repercussions. French expansionism played a crucial role in igniting Haiti’s “sugar revolution” in the early 1700s, steering the nation’s economy towards labor-intensive sugar plantations. By employing enslaved individuals and using violence against political adversaries, plantation owners significantly shaped Haiti’s current geography and its position within the global economy, forming an exploitative system benefiting a privileged minority.

While extensive discussions have taken place regarding how the Haitian Revolution of 1789-1804 (and the 1825 “indemnity” Haiti consented to pay France) influenced the country’s forward trajectory, the occurrences of the early 1700s shed light on the broader context.

“This is a pivotal moment in Haiti’s history that many people are not aware of,” states MIT historian Malick Ghachem. “And it occurred long before independence. It traces back to the 18th century when Haiti became entangled in debtor-creditor dynamics from which it has struggled to break free. The 1720s were when these relationships solidified.”

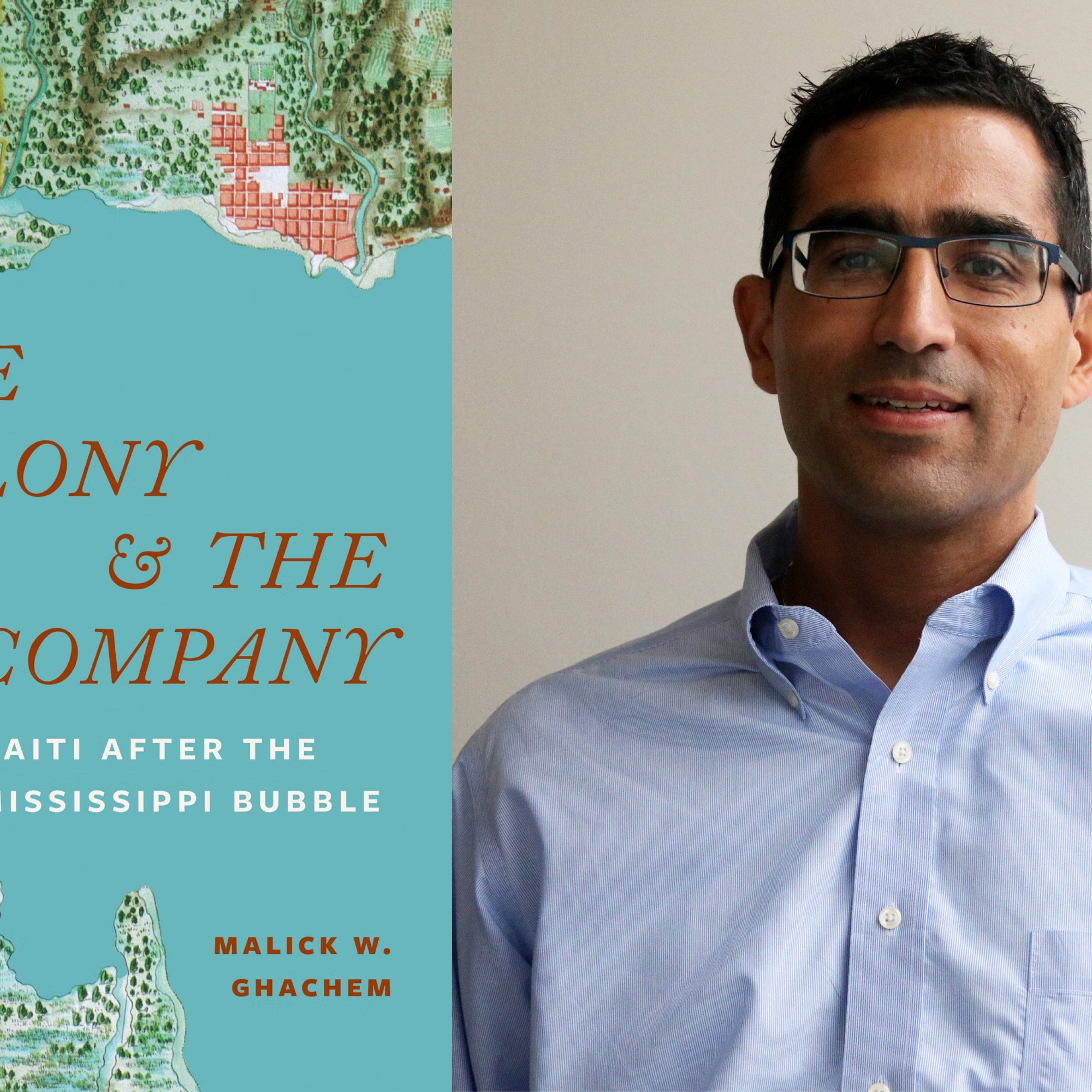

Ghachem delves into the economic shifts and multifaceted power conflicts of that era in a new publication, “The Colony and the Company: Haiti after the Mississippi Bubble,” released this summer by Princeton University Press.

“How did Haiti come to exist in its current state? This is the question everyone asks about it,” notes Ghachem. “This book aims to contribute to that discussion.”

Tangled in the crisis

Ghachem serves as both a professor and the leader of MIT’s history program. A trained attorney, his research spans France’s global narrative and American legal history. His 2012 work “The Old Regime and the Haitian Revolution,” also set in pre-revolutionary Haiti, explores the legal framework surrounding the push for liberation.

“The Colony and the Company” leverages original archival research, arriving at two interconnected conclusions: Haiti was integral to the global bubble of the 1710s, and that bubble and its aftermath are significant chapters in Haiti’s history.

At that time, until the late 1600s, Haiti, known as Saint Domingue, was “a delicate, mostly unregulated, and sparsely inhabited territory of uncertain trajectory,” as Ghachem writes in his book. The formation of Haiti’s economic structure is not merely the backdrop for subsequent events but a formative moment in its own right.

While the “sugar revolution” may have materialized in Haiti at some point, it was intensified by France’s pursuit of new revenue sources. Louis XIV’s military campaigns had inflicted severe fiscal strain on France. Law—a convicted murderer and evidently an effective marketer—suggested a restructuring plan that centralized revenue generation and other fiscal powers within a monopolistic foreign trading firm and bank overseen by Law himself.

As France sought to expand economically beyond its borders, this led the company to Haiti to exploit its agricultural potential. Moreover, as Ghachem elaborates, multiple nations were extending their overseas ventures—France, Britain, and Spain notably increased slave trade activities. Within just a few decades, Haiti emerged as a hub of global sugar production, reliant on slave labor.

“When the company is viewed as the solution to France’s woes, Haiti becomes enmeshed in the crisis,” Ghachem asserts. “The Mississippi Bubble of 1719-20 was essentially a worldwide event. And one of the stages where it unfolded most vividly was Haiti.”

In Haiti, however, this dynamic was intricate. Local planters resisted accountability to Law’s company and pushed back, yet, as Ghachem writes, they “absorbed and privatized the financial and economic logic of the System against which they had rebelled, transforming it into a framework for managing plantation society.”

This society was complex. A key aspect of “The Colony and the Company” is the examination of its intricacies. Haiti was home to a diverse population, including Jesuit missionaries, European women resettled there, and maroons (freed or escaped slaves living independently), among others. Plantation existence was marked by violence, civic unrest, and a lack of economic options.

“The so-called ‘success’ of the colony as a French economic powerhouse is inextricably linked to the conditions that hinder Haiti from thriving as an independent state after the revolution,” Ghachem observes.

Revisiting stories

In public conversations, inquiries regarding Haiti’s past are often deemed highly significant to its present situation as a near-failed state, where its capital is now heavily influenced by gangs, and violence shows no signs of abating. Some draw a direct line between present dilemmas and Haiti’s revolutionary-era circumstances. However, to Ghachem, the revolution altered certain political dynamics but did not change the fundamental living conditions in the country.

“One perspective is that it is the Haitian Revolution that results in Haiti’s impoverishment, violence, political disarray, and economic stagnation,” Ghachem states. “I find that argument flawed. It’s an older issue rooted in Haiti’s relationship with France in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. The revolution exacerbates that challenge and does so significantly due to the way France reacts. Yet the basis of Haiti’s subjugation was already established.”

Other academics have lauded “The Colony and the Company.” Pernille Røge from the University of Pittsburgh has termed it “a deeply nuanced and profoundly engaging history grounded in a meticulous analysis of both familiar and less familiar primary sources.”

For his part, Ghachem aspires to encourage anyone intrigued by Haiti’s past and present to adopt a broader perspective on the topic and contemplate how the deep-seated roots of Haiti’s economy have helped shape its society.

“I aim to fulfill the responsibilities of a historian,” Ghachem says. “Which includes uncovering stories that are not widely known, or are known but have elements that are undervalued, and presenting them in a new perspective.”