“`html

Kristen Johnson, AB ’00, and Catherine Stites, JD ’96, both operate, as they put it, “on the river.” The river in question flows through the southwestern terrain more than 100 miles from their workplaces in Phoenix and Los Angeles, respectively, but it’s never out of their thoughts.

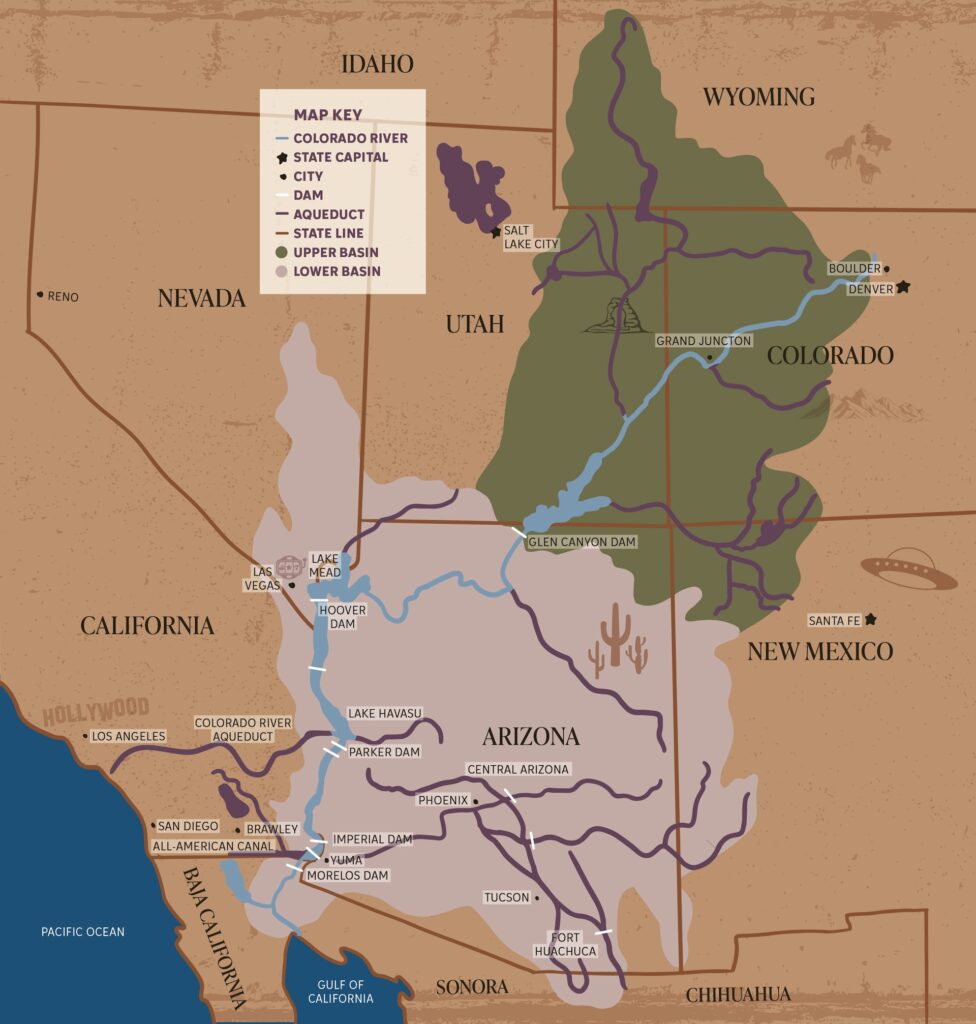

Tens of millions of individuals across seven states stake their claim to water from the Colorado River. Everyone desires their portion, including the residents and industries in Arizona and California that Johnson and Stites advocate for. However, as climate change advances, there is increasingly less to share each year.

“We’re involved in a very intricate dance at present concerning the river,” asserts Johnson, the Colorado River programs manager at the Arizona Department of Water Resources. “The seven states are in a challenging situation trying to negotiate how to oversee the river for the next 10 to 20 years.”

“When resources are limited and you’re trying to establish who bears the loss and to what extent — well, nobody is eager to go first.”

Currently, the lower basin states — Arizona, California, and Nevada — are somewhat harmonizing, exchanging proposals on how to modify existing agreements to prepare for a future with diminished resources. But, with a deadline approaching, there’s a broad acknowledgment of how swiftly the situation could alter. The current operational guidelines for the river will conclude at the end of 2026.

“In the lower basin states, we’re cooperating, but these matters can rapidly escalate,” states Stites, who serves as principal deputy general counsel with the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California. “Kristen and I are presently on the same side. It’s quite collegial and professional, even amicable. We collaborate effectively on river-related matters,” she continues, before pausing momentarily. “Even if we might ultimately end up litigating against each other.”

The rule of the river

In 1922, for the first time in U.S. history, more than three states convened to allocate a shared river resource. According to the Colorado River Compact, the upper basin — consisting of Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming — and the lower basin would each receive 7.5 million acre-feet of water annually, with a lesser amount allocated for Mexico. (An acre-foot is approximately 326,000 gallons, enough water to cover an acre of land with one foot of water.)

However, there was a minor issue with the 1922 figures that, over the span of more than a century, has led to a significant distribution challenge. “We know now that the early 1920s was a notably wet era,” Johnson explains, with an average flow of around 16 to 17 million acre-feet yearly. “Today, we’re witnessing a river yielding about 12 million acre-feet. In the future, as we grapple with climate change, we’re preparing for an 11- or even 10-million-acre-foot river.”

This disparity, along with the rapid increase in population and water-intensive sectors like agriculture, mining, and hydropower, has rendered the historical compact merely a starting point. Continuous negotiations have persisted among governments, Indigenous tribes, businesses, environmental organizations, and individuals contending for water rights.

Enter the Law of the River, the shorthand term for the intricate web of laws, judicial decisions, agreements, and treaties layered upon the original 1922 compact. Under the Law of the River, entities have contracts with the federal government that grant them specific allocations of water. Additionally, there exists a priority system, with the highest priority assigned to agricultural regions like Yuma, Arizona, and Imperial, California, which together produce more than 90% of North America’s winter vegetables.

“Understanding how that body of law integrates together to see where we stand today, and how the river is administered, is a crucial aspect of my daily work.”

Kristen Johnson, AB ’00

“Understanding how that body of law integrates together to see where we stand today, and how the river is administered, is a crucial aspect of my daily work,” Johnson states, though she is not acting in a legal capacity in her current position. “Any matters related to Colorado River entitlements, the volume allocated to Arizona, and our division of it, come through me and my team.” Some days may involve discussions with a farmer seeking to sell or partition their water rights; other times could be spent reviewing hydrologic models or contemplating requirements for the preservation of endangered species.

Across the state boundary in California, Stites manages the intricate legal requirements associated with providing water to approximately 19 million urban inhabitants. The Metropolitan Water District of Southern California encompasses major urban areas like Los Angeles and San Diego, and it is perpetually developing or enhancing infrastructure to treat and transport water. Stites oversees environmental impact reports and compliance with the California Environmental Quality Act for these initiatives. In addition to her emphasis on Colorado River matters, she addresses tribal claims for water rights.

“Without the Colorado River water supply, Southern California would not have been able to evolve into what it has become today,” Stites remarks. “If California were an independent nation, we’d rank as the fourth-largest economy globally.”

Currently, about 20% of the district’s water continues to originate from the river. Other supply sources in Southern California include groundwater as well as desalinated or recycled water.

“One fundamental truth about water: It’s heavy. Transporting, treating, and delivering water is extremely costly due to its incredible weight. Much like with your retirement planning, we need to adopt a diversified approach to our water supply.”

Negotiation and teamwork

From her perspective as a longtime leader on the federal scene, Rachel Jacobson, AB ’80, recognizes the stakes associated with effective water management. “Water is becoming increasingly limited, while the demand for it is rising. That intersection can create potential security challenges around the globe,” Jacobson remarks.

Though she quickly emphasizes that she is not a water attorney by profession, Jacobson has held numerous governmental roles related to water management and policy. At the Department of Justice, she enforced the Clean Water Act. While at the Department of the Interior, she addressed environmental conservation efforts in the Everglades and directed settlement discussions with BP following the Deepwater Horizon oil disaster. In her tenure at the Department of Defense, she offered legal guidance on environmental regulations.

“““html

and initiatives. Most recently, she held the role of assistant secretary of the U.S. Army for installations, energy, and environment.

“Within the Army, we were extremely aware of the necessity for water preservation,” she notes. As assistant secretary, Jacobson oversaw physical infrastructure and natural resources across numerous military facilities.

She highlights Fort Huachuca in Arizona as an exemplary case. Today, the base accommodates the U.S. Army Intelligence Center of Excellence and serves as a critical testing ground for unmanned aerial vehicles. The drought-affected region is also home to agricultural land and ranches. With various competing interests, providing sufficient water for military operations necessitates strong collaborations, Jacobson states.

“As a lawyer, the inclination is often to push for 100%. However, that approach isn’t effective for successful water management.”

Rachel Jacobson, AB ’80

“Congress allocates funding to military departments for promoting conservation methods off base that, in turn, enhance military readiness,” she clarifies. This authorization allows Fort Huachuca to collaborate with local landowners and agencies to safeguard groundwater. The base has also established a comprehensive wastewater recycling facility. These initiatives earned the base a Sentinel Landscape designation, indicating its role as a conservation benchmark for other military locations. Jacobson believes the results there also provide valuable insights for the larger region and nation.

“There needs to be a framework of collaboration,” she emphasizes. “In my view as a lawyer, the tendency is to advocate for a 100% solution. But that doesn’t facilitate effective water management. Without cooperation among stakeholders, conflicts and legal disputes will arise. And certainly, no one wants a judge adjudicating how much water should be distributed and where along the Colorado River, right? Policy leaders must always stay focused on this issue. No party will get everything they desire. Water is finite.”

Beyond the river

Individuals outside the Colorado River Basin are not exempt from the water shortages and difficulties impacting the area. Thor Larsen, BSBA ’98, has established his residence in the Sierra Nevada foothills in northern California, where he functions as the water resources superintendent for the Nevada Irrigation District. The district spans nearly 300,000 acres, with everyone from farmers to leisure boaters relying on snowmelt and surface water to satisfy their needs.

“Navigating the myriad demands for water supply presented intriguing challenges,” Larsen reflects on his choice to pursue a career in water management. After a brief period in commodities trading post-graduation from WashU, he returned to his home state of California. Now, as superintendent of a large irrigation district, his team monitors water supply and movement through snow sampling, satellite imagery, and additional methods.

“We experience significant variability between different water years,” Larsen explains. “We can have a few years of drought followed by flooding in the next year. The main concern is maintaining reliability for our constituents.”

Considering long-term climate trends, he recognizes the necessity for constructing or enlarging reservoirs to capture more water during wetter periods. “With rising temperatures persistently occurring year after year, we observe a decrease in snowpack and an increase in snow elevation. We will need to find alternative ways to compensate,” Larsen adds. “I’m uncertain if any new reservoirs will be built within my lifetime, but pursuing increased storage is a direction that must be explored.”

While planning for future projects, Larsen confronts more immediate obstacles. This year, infrastructure managed by Pacific Gas and Electric was offline for several months, resulting in water restrictions. Additionally, an invasive mussel species recently emerged in other Californian waterways, necessitating inspections and quarantine measures to avert further spread.

The dizzying array of responsibilities and partners makes the role exciting for Larsen, a sentiment echoed by both Stites and Johnson. “Managing the diverse stakeholders and crafting the right messaging is such an intellectual challenge,” Johnson comments.

Stites has been engaged in water law since the summer following her first year at WashU Law, where she enrolled in environmental law courses and participated in the environmental law society. “At that time, environmental law was quite avant-garde,” she shares. She worked at several private law firms before transitioning to Metropolitan 20 years ago.

“When I came on board, I found the work fascinating,” Stites notes. “We are the largest wholesale water supplier in the nation, and most of the individuals we collaborate with are engineers. I truly enjoy working with such intelligent and talented individuals.”

Johnson, who studied anthropology at WashU prior to obtaining a law degree from Southern Illinois University, was drawn to the western U.S. after participating in a WashU fieldwork project digging for fossils in Utah. As a “suburban Chicago kid,” she was captivated by the desert scenery. “Had it not been for that field season and that experience, my life would be very different,” she states. A subsequent summer legal internship at the Department of the Interior solidified her passion for water resource management.

“Ultimately, my specialization found me,” Johnson remarks. “And I am incredibly grateful.”

Living with less

In the ongoing discussions among the states, countless questions and scenarios are considered: What is the essential minimum amount of water required for human health and safety, including fire prevention? If severe drought conditions necessitate redirecting water from one location to another to meet that minimum requirement, who receives the reduction? Under what circumstances do those with senior water rights, including Yuma County, need to cut back? And who compensates whom for all that water?

In each of these scenarios, individuals in the Southwest will have to learn to get by with less water than before. In fact, they already are.

“Current regulations are already causing reductions for some,” Johnson observes. “We have been experiencing a shortage situation since 2022.” The region garnered media attention in early 2023 when Lake Powell dropped to its unprecedented low height above sea level.

Fortunately, water conservation initiatives are making significant strides. “Per capita water use in urban areas and within Metropolitan’s service area has decreased by half compared to previous usage,” Stites indicates. “Even with the dramatic population growth since the 1990s, we are not consuming more water.”

This reduction has stemmed from the use of low-flow toilets and appliances, the rise of drought-tolerant “California-friendly” gardens, alterations in building codes, and additional factors. Stites commends neighboring Nevada for its superior efforts in water recycling and conservation — aspects that are often overlooked by visitors enjoying the attractions of Las Vegas.

Across all sectors, there is also heightened investment in water treatment technologies to ensure every available drop is safe for consumption. Metropolitan is allocating approximately $7 billion to develop a vast recycled-water facility in Los Angeles, part of a multi-phase initiative to treat LA’s wastewater.

“““html

drinkable. This crucial commitment to water quality, alongside its availability, places the region in alignment with initiatives at WashU and nationwide.

Daniel Giammar, the Walter E. Browne Professor of Environmental Engineering at the McKelvey School of Engineering and director of the Center for the Environment, has collaborated with Metropolitan to analyze the effects of mixing traditional water sources with advanced treated water, investigating the release of metals from residential plumbing.

“We received routine deliveries of this advanced treated water at our lab at WashU, where we conducted managed laboratory experiments,” Giammar mentions. That investigation was backed by the Water Research Foundation. Last year, he was appointed by the National Water Research Institute to participate on an independent scientific advisory panel that will evaluate Metropolitan’s strategy for direct drinkable reuse.

Through a project named Trusted Tap, funded by the National Science Foundation, Giammar’s research holds the promise of aiding those residing far beyond the Colorado River Basin. With a multidisciplinary team of scientists and engineers, Trusted Tap is being created to provide a straightforward method for monitoring tap water for pollutants such as lead and PFAS “forever” chemicals. In this method, users are required to send their current water filters (like those produced by Brita or Pur) to Trusted Tap for examination. Notably, Trusted Tap has the capability to assist any water user, including the millions of Americans who depend on private wells.

Giammar is also among more than a dozen faculty members from McKelvey and Arts & Sciences associated with WashU’s Center for Water Innovation. The center promotes collaborations and research that advance sustainable water and wastewater management. Its director, Zhen (Jason) He, the Laura and William Jens Professor of Energy, Environmental & Chemical Engineering, specializes in recovering valuable resources from wastewater. The center’s local partners include the City of St. Louis Water Division and the American Bottoms regional wastewater treatment facility.

Those engaged in water management regard such collaborations as vital to addressing persistent challenges in the West and beyond. Specialists in policy, engineering, energy, law, the environment, communications, and more are essential, as are individuals who dedicate their careers to the mission.

“I believe it’s an honor to work in this field,” Johnson states. “We ought not to undervalue water any longer. It’s fundamental to everything we undertake.”

The post The weight of water appeared first on The Source.

“`