Campus & Community

Researchers of slavery pursue a more comprehensive view of pre-Civil War Harvard

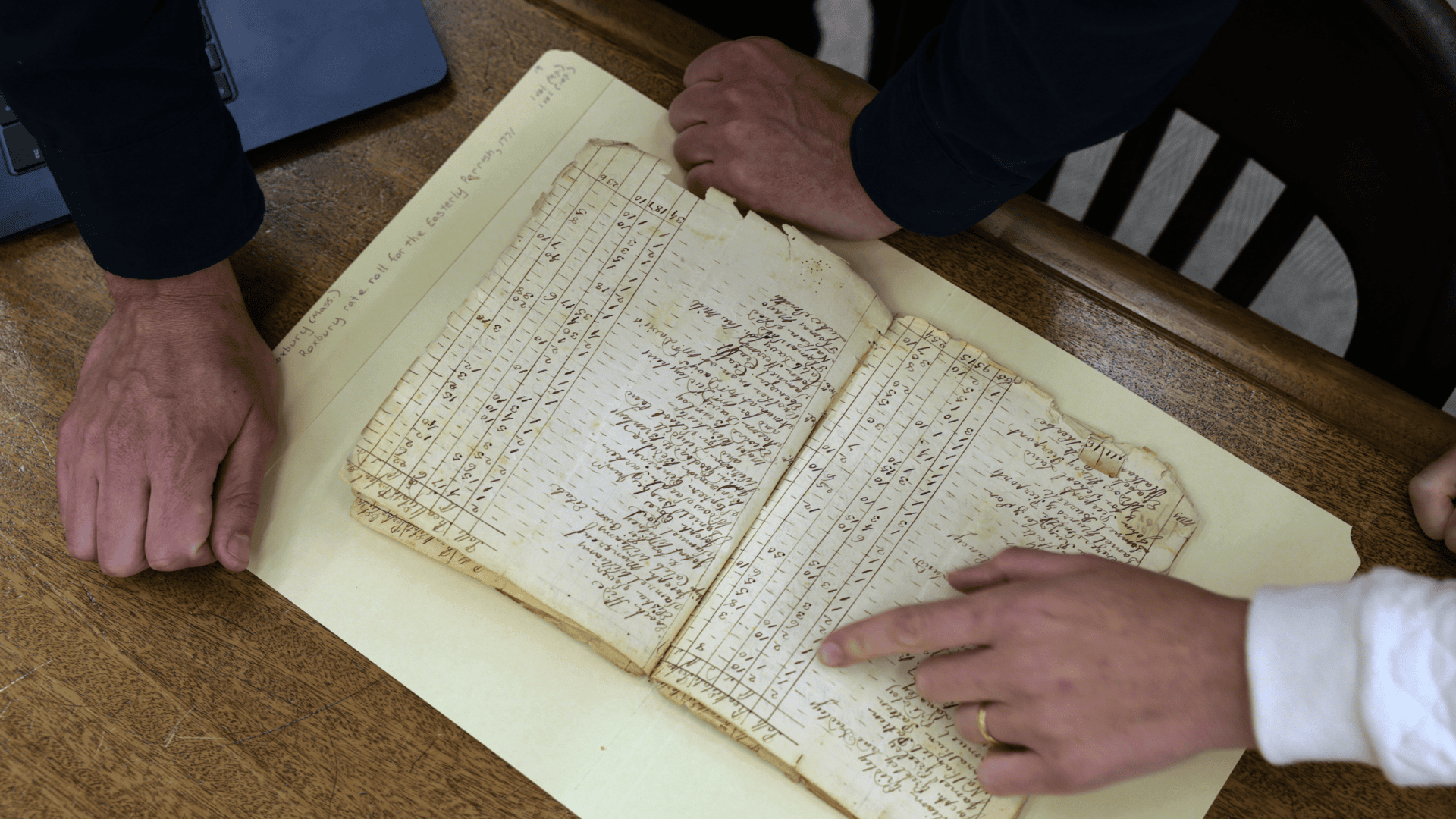

Gabriel Raeburn and Christine Bachman-Sanders examining documents.

Photo courtesy of Claire Vail at American Ancestors

Thorough efforts to identify leaders, faculty, and staff are vital to descendants investigation: ‘This task requires time to accomplish properly’

In their endeavors to trace descendants of enslaved people connected to Harvard, researchers with American Ancestors initially faced a surprisingly challenging question: Who were the University’s leaders, faculty, and staff prior to the Civil War?

Presently, a previously scattered record is progressively coming into clarity.

The initiative began shortly after the University acknowledged the recommendations of the Presidential Committee on Harvard & the Legacy of Slavery, aimed at identifying, engaging, and assisting direct descendants of slavery. In their report, published in 2022, the committee recognized several Harvard leaders, faculty, and staff who held enslaved individuals. This group included philanthropist Benjamin Bussey, who amassed wealth through the transatlantic trade of products generated by enslaved people and subsequently donated his estate to Harvard College, and steward Andrew Bordman, who owned and depended on eight enslaved individuals to sustain Harvard students and fulfill his job responsibilities.

Initiatives to identify pre-Civil War leaders, faculty, and staff have been ongoing since 2023, alongside research to pinpoint direct descendants of enslaved individuals. Researchers with the Harvard Slavery Remembrance Program spearheaded this segment of the task, while American Ancestors progressed the direct descendant research. In January, American Ancestors also led the research to pinpoint Harvard officials.

“At first glance, it seems like a simple task to ‘identify leadership, faculty, and staff,’” remarked Lindsay Fulton, chief research officer at American Ancestors. “But that’s a contemporary viewpoint shaped by access to yearbooks, alumni directories, and meticulously kept records. These resources didn’t always exist, requiring our researchers to adopt creative methods in discovering where and how these names were recorded. In our experience, this work requires time to execute properly.”

“These resources didn’t always exist, requiring our researchers to adopt creative methods in discovering where, and how, these names were recorded. In our experience, this work requires time to execute properly.”

Lindsay Fulton

For more than 200 years — from Harvard’s establishment in 1636 to the conclusion of the Civil War in 1865 — the University operated during a time when slavery was legal in various parts of the U.S. Even after 1783, when slavery was effectively prohibited in Massachusetts, leaders, faculty, and staff could still become owners of enslaved individuals, frequently referred to as servants, through family ties or operate businesses closely linked to the labor of enslaved people.

While positions such as the University’s president and treasurer are relatively straightforward to trace through historical records, others are significantly more complex.

Gabriel Raeburn reviewing documents with fellow researcher Christine Bachman-Sanders.

Photo courtesy of Claire Vail at American Ancestors

“The University doesn’t maintain its own compiled digital staff directory prior to the modern era,” noted Gabriel Raeburn, senior research project manager at American Ancestors. “The initial step, even for finding enslaved individuals, involved sifting through thousands of pages of dense archival records in 17th- and 18th-century cursive to ascertain who the individuals were that worked at the University.”

To identify leaders, faculty, and staff, researchers persist in examining handwritten notes from University meetings, along with records of stewards, faculty documentation, colonial and state legislative charters, church rosters, city archives, and a diverse range of other sources to reconstruct a list from scratch. Through this initiative, researchers at the Harvard Slavery Remembrance Program and American Ancestors have confirmed over 3,000 individuals in leadership, faculty, and staff roles from this era.

A foundation for deeper understanding

Determining who worked at pre-Civil War Harvard often initiates with pieces of information: a brief reference in long-past meeting notes, a class register. Knowing the composition of leadership, staff, and faculty in Harvard’s early history necessitates a profound comprehension of the University’s associations with colonial and local church leadership and a knowledge of where to investigate. Uncovering this information utilizes established genealogical methodologies that the researchers at American Ancestors adeptly employ.

For instance, for two centuries, specific members of colonial government and ministers from local towns and cities were automatically given roles on Harvard’s Board of Overseers. Thus, researchers turned to legislative acts and Harvard’s colonial charters to determine which positions were automatically conferred leadership roles — such as the Congregational ministers from Boston, Cambridge, Charlestown, Watertown, Dorchester, and Roxbury — and are utilizing church records to identify which individuals served on Harvard’s board.

These contextual approaches are particularly crucial to bridge gaps in Harvard’s own archives. One such gap arose from a fire in 1764 that obliterated a significant portion of the University’s collections.

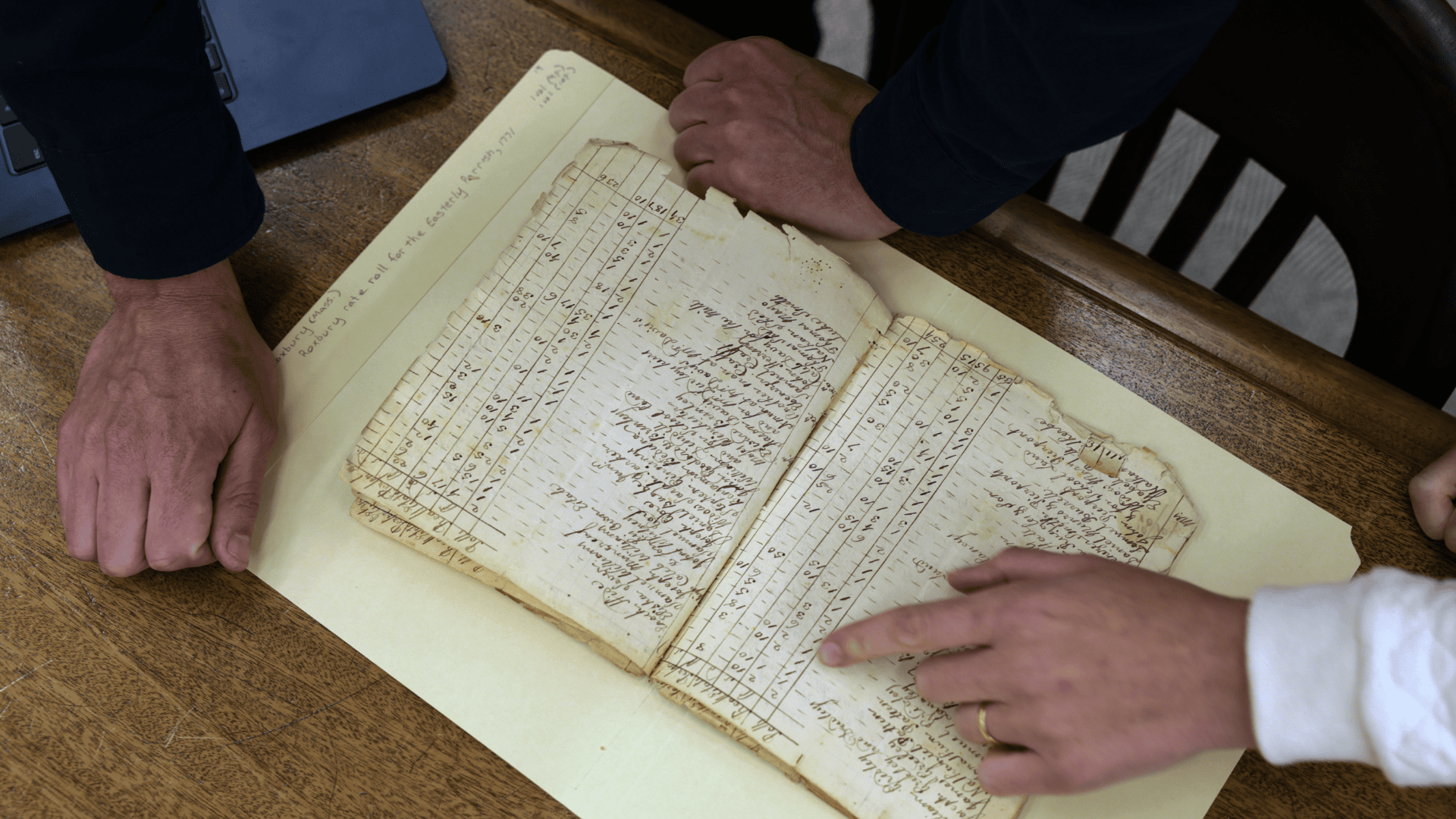

At the base of these handwritten records from a 1737 assembly between president and faculty, six new waitstaff are noted by surname.

Harvard University, Harvard University Archives, UAI5_5_B08_V12-METS

Moreover, for those lacking extensive exposure to records-based genealogy, interpreting the documents that the University possesses can be challenging. Most are composed in handwriting of varying legibility and consistency.

Researchers also need to know where to search. For instance, in the earlier years of the University’s existence, it was during Harvard Corporation meetings where leaders appointed compensated personnel — often current or recently graduated scholars. Typically, record keepers did not note the new personnel by complete name. Instead, they are often referenced by surname, and in instances where there are multiple students at Harvard sharing that name, by a sign of seniority. For example, an individual named Smith appointed as head cook might be labeled as Smith Jr.

Genealogists at American Ancestors now utilize a system for categorizing individuals with identical surnames. For specific eras in University history, discerning which Smith was appointed to a new role involves sifting through records and determining which Smith was the youngest at that time. In other periods, whether an individual was referred to as senior, junior, III, or IV was contingent on their relative social rank. Both tasks require researchers to examine contemporary records and pinpoint the correct Smith. Occasionally, differentiating between family members necessitates searching through birth and death records maintained both in Massachusetts and nationwide.

Grasping who worked at the University enables researchers to further investigate whether these individuals owned enslaved people. It also provides researchers with a comprehensive overview of the intertwined names, families, and communities that shaped Harvard.

“These individuals did not function in isolation,” stated Fulton. “They studied together, taught together, published together, worshipped together, and often their children intermarried. Comprehending this intricate, living network makes our conclusions more thorough, more precise, and more representative of the institution’s genuine historical landscape.”

“Comprehending this intricate, living network makes our conclusions more thorough, more precise, and more representative of the institution’s genuine historical landscape.”

Lindsay Fulton

During the timeframe examined by researchers, the size of the University — both students and staff — saw significant growth. Harvard’s inaugural graduating class, in 1642, encompassed just nine students. Throughout the 17th century, there were five years without any graduates. Accurate records of staff and faculty were sometimes difficult to obtain. Over the years, the number of Harvard faculty, staff, and students increased, and the documentation improved. By 1860, Harvard conferred over 200 degrees across the College, Medical School, and Law School.

As the University expanded, the number of individuals to scrutinize escalated, but documents produced during these periods assist in streamlining the process. For example, entries in the Massachusetts Register, published annually by the state since 1767, documented each new appointment to the University. Researchers can refer to these lists and corroborate them with primary sources.

‘Marathon of research’

This endeavor to establish a comprehensive list of Harvard leaders, faculty, and staff is enabling American Ancestors not only to more accurately identify individuals who enslaved people but also to begin uncovering the names of those who were enslaved — ultimately tracing their living descendants.

The researchers emphasize that various facets of this work continue concurrently. In addition to identifying former University leaders, faculty, and staff, contributors to the Harvard Slavery Remembrance Program are working to identify those who were enslaved and their living descendants. As of now, 964 previously enslaved individuals and 591 living descendants of these individuals have been recognized.

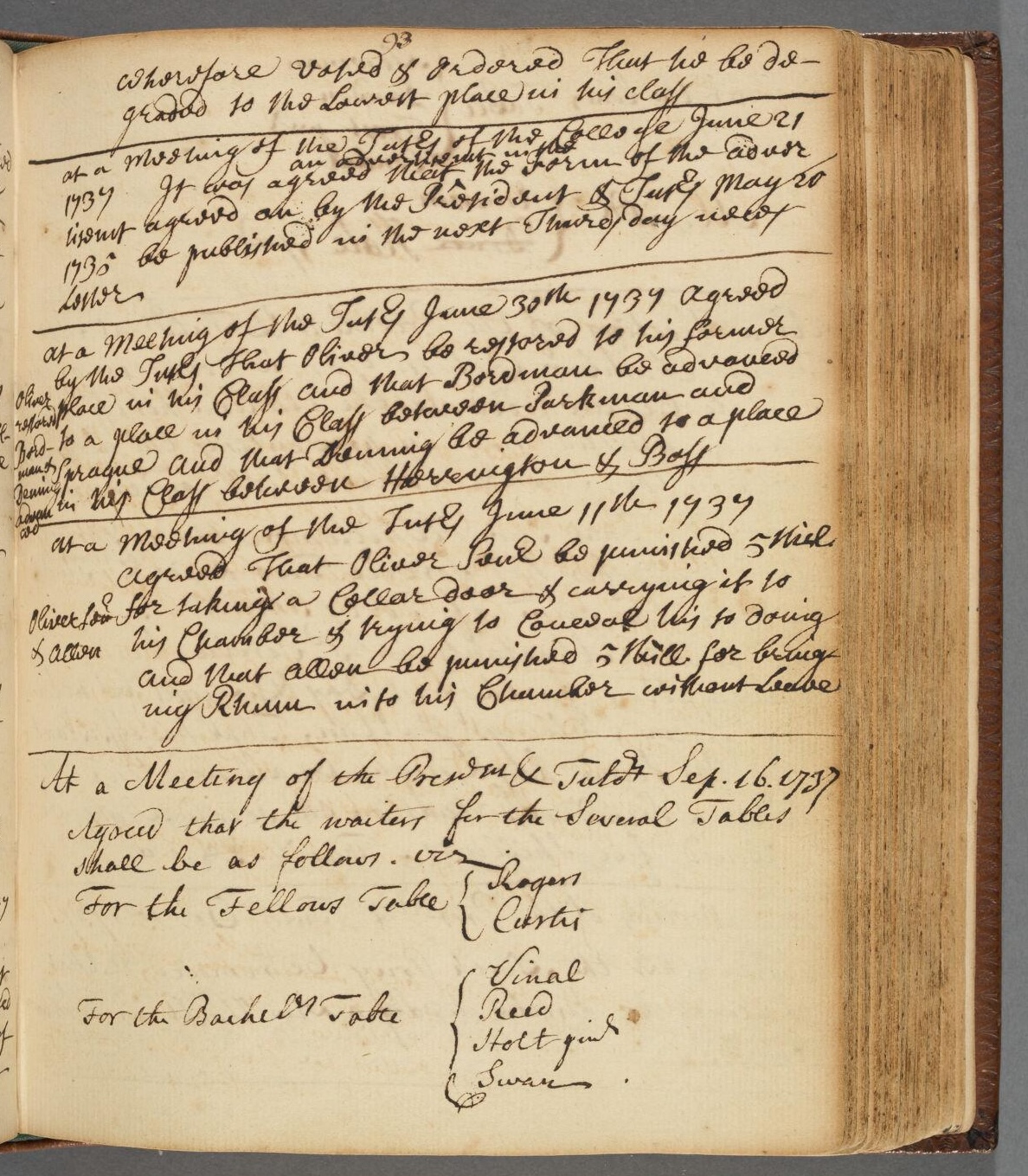

After pinpointing members of Harvard’s faculty, staff, and leadership, researchers from American Ancestors turn to more historical documents, like tax lists, to identify individuals who enslaved people.

Photo courtesy of Claire Vail at American Ancestors

The meticulous nature of records-based genealogy is slow, and the scope can be challenging to forecast. On television programs like “Finding Your Roots,” hosted by Alphonse Fletcher University Professor Henry Louis Gates Jr., guests discover their genealogy in a single episode. However, in reality, the genealogical work behind each episode of “Finding Your Roots,” which is verified by American Ancestors and focuses on an individual, takes approximately six months.

“Genealogical research is painstaking work — studying centuries-old records, tracing forgotten names, and piecing together narratives that have often been lost or obscured,” noted Gates. “It necessitates not only patience and rigor but also a passion for discovery. That’s why American Ancestors is the ideal organization to undertake this work for Harvard. Their profound expertise, meticulous focus on detail, and steadfast commitment to revealing the stories of our past render them uniquely suited to take on this essential task.”

“Genealogical research is painstaking work — studying centuries-old records, tracing forgotten names, and piecing together narratives that have often been lost or obscured.”

Henry Louis Gates Jr.

According to American Ancestors researchers, the identification of a clear list of pre-Civil War leaders, faculty, and staff will lead to a more comprehensive understanding of the University’s connections to slavery — and establish a valuable foundation for future research and engagement with living direct descendants. Fulton mentioned that the 3,000 individuals identified as leaders, faculty, and staff surpassed their initial estimate and provided the team with a more precise — and expansive — view of their efforts.

“Getting this right is critical — it’s the starting line for what will be a marathon of research,” Fulton stated. “And in a marathon, you don’t want to set off in the wrong direction and realize halfway through that you need to backtrack.”

“`