“`html

Science & Tech

‘She possessed a profound care for everyone she met.’

Jane Goodall addressing an audience at Harvard after being awarded the Roger Tory Peterson medal in 2007.

Image courtesy of Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

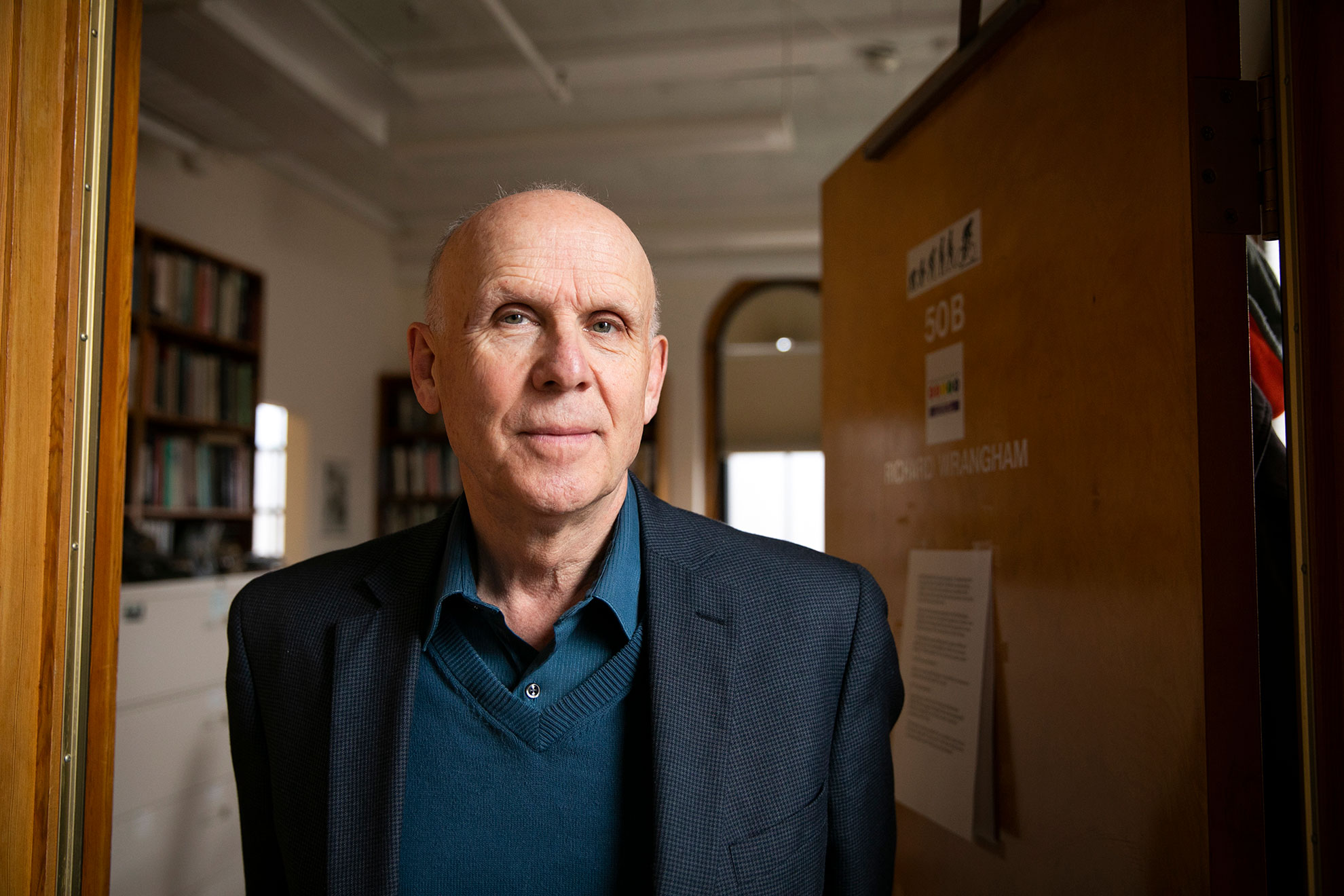

Richard Wrangham reflects on his mentor and peer Jane Goodall as a beacon of scientific inquiry, compassion, and optimism

Upon the passing of the scientist and conservationist Jane Goodall last week, she bequeathed a revolutionary perspective on humanity’s bond with its nearest primate relatives — chimpanzees — along with a legacy that underscores the significance of this connection in comprehending ourselves.

Richard Wrangham, Harvard’s Ruth Moore Professor of Biological Anthropology, emeritus, and a prominent expert in chimp behavior, collaborated with Goodall, first as a student and later as a colleague after he established the Kibale Forest Chimpanzee Project in Uganda. In this revised dialogue, he elaborates on her broader influence as an educator — not solely for her peers and fellow researchers but also as a symbol of hope and empathy.

You conducted graduate studies at the Gombe Stream in Tanzania. How was that experience?

It was truly enchanting. I was engaged in research at Gombe, a stunning region characterized by semi-forested, semi-bush, and semi-grassy landscapes cascading towards a brilliant blue lake. Approximately 60 chimpanzees roamed through the hills and valleys, their behaviors remaining largely enigmatic. Each day was exhilarating.

Jane began her journey in 1960, excellently tracking the chimps, locating them, and observing them in their natural habitat, gradually learning to recognize them as individuals by staying in a small camp. Beginning in 1969, students began following the chimps wherever they ventured. I joined this group in 1970. We uncovered, for instance, that the chimps maintained a territory which they defended against competing groups, raising numerous intriguing questions.

During this period, Jane primarily focused on the Serengeti, studying carnivores. She would visit Gombe for week-long stints, which was delightful as she was eager to learn everything about the chimps’ activities. Her interests were broad-ranging.

Richard Wrangham.

Image courtesy of Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer.

How would you portray her as an individual?

Extraordinarily focused. One aspect not everyone acknowledges is that Jane transcended the image of a courageous young woman familiarizing herself with chimps in the woods. She was an exceptional scientist, combining detailed observation with a robust theoretical insight. We were fortunate that Jane was among the pioneers studying wild chimpanzees because she excelled at it.

Is there a particular trait or accomplishment you believe she should be most recognized for?

One response pertains to the unifying theme of her endeavors, and I believe that’s empathy: empathy towards chimps, empathy for the communities surrounding the chimp habitats — conservation should not come at the expense of human lives — empathy towards the planet, and empathy for all living beings. She exhibited a genuine concern for every individual she encountered.

It’s well-known that she remained laser-focused on chimpanzee behavior and their natural history until 1986. Her perspective shifted after attending a Chicago conference titled “Understanding Chimpanzees.” There, she learned during the conservation session about the dire situations facing chimps. She became aware of the harsh realities of chimpanzees often confined in captivity, leading her commitment to conservation and care to eclipse her research pursuits. This unwavering focus was likely a factor in her tremendous success.

Your work alongside hers has revolutionized our perception of humanity’s nearest primate relative. What insights do we possess now that we previously lacked?

When Jane initiated her work in the 1960s, there was little reason to consider any great apes as particularly significant for grasping human evolution, yet she revealed far greater similarities in behaviors between chimpanzees and humans than between humans and what was understood at that time about gorillas and orangutans.

Subsequent DNA analysis would later demonstrate that chimpanzees are more closely related to humans than they are to gorillas. Her groundbreaking findings on tool-making, tool-using, sharing food, hunting, aggressive behavior, as well as the profound connections seen in mother-infant bonds — all of which unite humans and chimps — laid the groundwork for the DNA breakthrough.

People began to take the idea of an underlying biological influence on human behavior far more seriously. She also played a pivotal role in convincing the scientific community that chimpanzees shared much more emotional similarity to us, in their capacity for emotions, and in their cognitive abilities than was previously recognized in any wild species.

Richard W. Wrangham (left) presenting Goodall with the Roger Tory Peterson medal in 2007.

File photo by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff

“““html

Photographer

Goodall was honored with the 2003 Global Environmental Citizen Award from Eric Chivian, who served as the director of the Center for Health and the Global Environment at Harvard.

Harvard file photo

Has her work influenced our treatment of chimpanzees?

It has had significant impacts. In the mid-twentieth century, there were numerous chimpanzees in research facilities that have since been transferred to sanctuaries, where they are cared for relatively comfortably in their later years without being confined to small solitary cages or subjected to distressing medical trials.

Some articles have portrayed her as an optimist, which appears somewhat unexpected considering humanity’s impact on the environment. Do you think that she was?

She firmly believed that it was essential for her to embody optimism because people require hope. Individuals need encouragement to engage in beneficial actions: for themselves, the planet, their communities, and wildlife. The books she authored in the last twenty years with “hope” in the title demonstrate a deliberate effort to sustain that hope. What was her true perspective? There’s no doubt that the challenges affected her, but I think she genuinely believed in reasons for optimism. One of her primary sources of hope was the resilient human spirit. If you remind individuals that through perseverance, they can achieve anything — a lesson from her mother — then positive outcomes will follow.

Do you share her sense of optimism?

I do not maintain an optimistic view about preserving anything resembling the current level of nature. I perceive the human species as inexorably taking over the vast majority of the natural world. I believe the future of our wild areas relies on concentrating efforts on the significant regions that will sustain as many species as possible. Kibale Forest is the largest forest in Uganda, and it’s rather small at only about 250 square miles.

The hope lies in keeping nations recognizing the value of preserving these unique locations. I fear that if we concentrate excessively on conserving every minor forest, we could overlook the bigger perspective. However, I can sense Jane watching me and saying, “You shouldn’t express that.” She would argue, “You should ardently advocate for every small forest, and perhaps that passion will generate momentum to protect the larger ones as well.”

“`