“`html

Arts & Culture

Reading as if it’s 1989

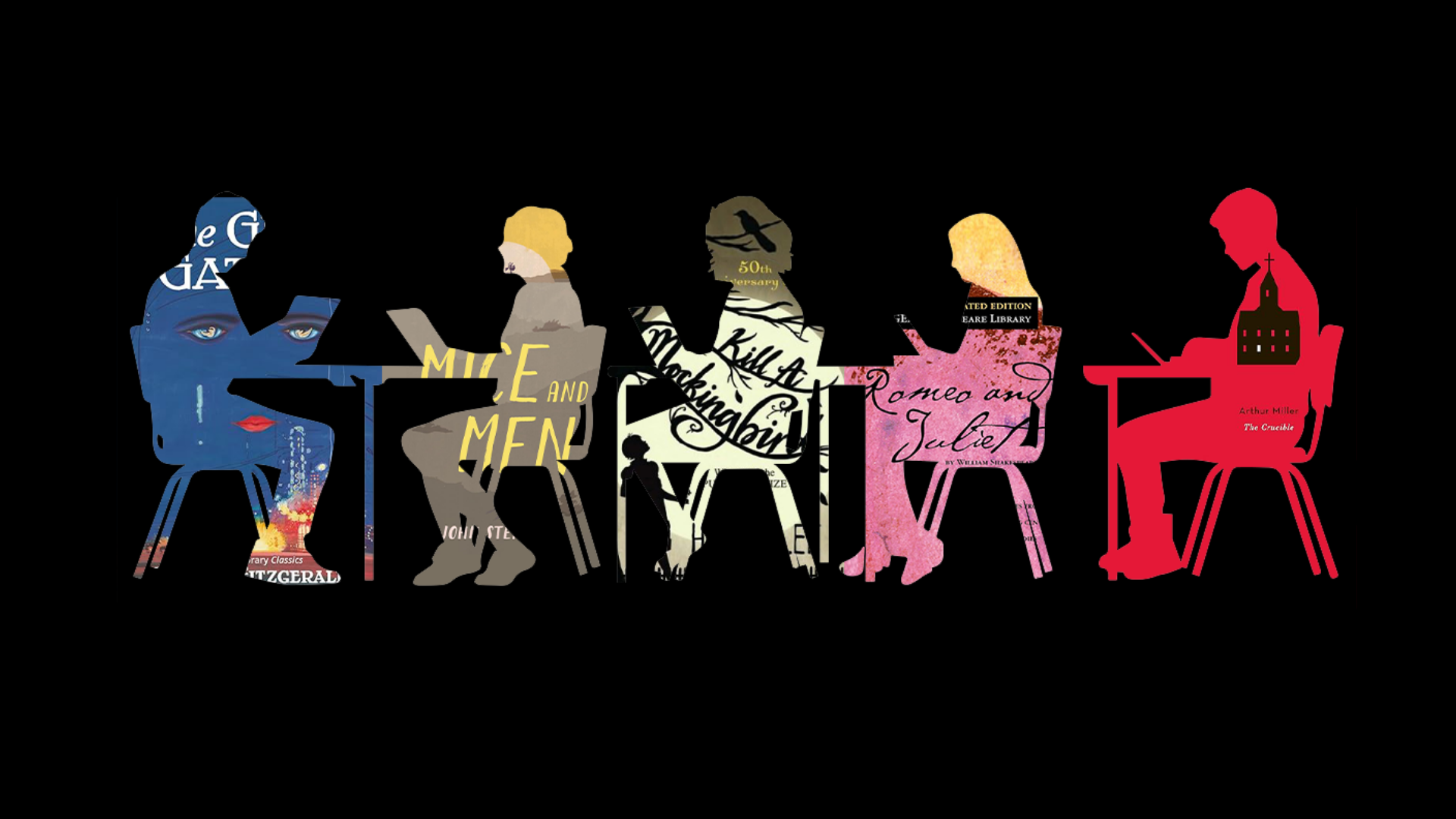

Illustration by Liz Zonarich/Harvard Staff

Study on classroom reading reveals lasting appeal for ‘Gatsby,’ ‘Of Mice and Men,’ and other timeless works. Is it time for a change?

Looking back four decades, you’ll notice significant transformations. The emergence of the Internet, the smartphone era, and now omnipresent AI. The conclusion of the Cold War and the beginning of numerous more complex conflicts. The upheaval of gender and sexuality norms, followed by various reactions.

What literature are youth engaging with to interpret their surroundings? A recent study indicates they are largely consuming the same material their parents did.

That study — conducted by researchers Kyungae Chae and Ricki Ginsberg for the National Council of Teachers of English — surveyed over 4,000 public school educators in the U.S. regarding the assignments they give to students in grades six through twelve.

The findings reveal minimal change at the pinnacle of the English syllabus. F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “The Great Gatsby,” John Steinbeck’s “Of Mice and Men,” and several Shakespeare tragedies fill half of the top 10 most-assigned works — just as they did in 1989. Even back in 1964, the top 10 was strikingly similar: While two Dickens novels have been excluded, “Hamlet” and “Macbeth” remain.

Classics are “classic” for a reason, naturally. However, this stagnation in English class corresponds with a trend that concerns educators, writers, and numerous parents: a prolonged decline in the reading habits of younger Americans.

Some are apprehensive that — in a varied and divided society — literature that once seemed attainable now appears distant or inaccessible, or that cultural conservatism or institutional education systems have hindered the curriculum’s healthy progression.

With numerous avid readers, Harvard’s classrooms host nearly as many perspectives on the issue, if it is indeed one, of curricular stagnation.

Stephanie Burt, the Donald P. and Katherine B. Loker Professor in the Department of English, garnered attention last year for launching a course focused on Taylor Swift. It was, in part, a purposeful attempt to utilize the world’s most renowned songwriter as a gateway to Wordsworth and hermeneutics.

However, Burt — also a practicing poet — remarked that her appreciation of Swift does not indicate she has sidelined, say, John Donne. Teaching Shakespeare to the younger generation, she expressed, is “not conservatism — it’s conservation, akin to preserving ancient forests.”

Rosette Cirillo, too, recognizes educational merit in true classics from the pinnacle of English literature — but for different reasons.

Currently, Cirillo is a lecturer and teacher educator at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. However, not long ago, she was instructing eighth-grade English in Chelsea, Massachusetts, a predominantly Latin-American community where close to half of the students are identified as English learners.

“If I had an eighth-grader who progressed to Harvard after graduating Chelsea High, and he had never encountered Shakespeare, he would face a significant disadvantage,” Cirillo stated.

And, she emphasizes, her argument leans less towards assimilation and more towards challenge.

“If I cannot grasp ‘The Great Gatsby’ — this narrative of the American dream — and the concept of a masculine transformation to achieve something, then I don’t fully comprehend the mythology of America enough to critique it, to express, ‘I don’t desire that,’” Cirillo mentioned. “We’re focusing on constructing a language and culture of power and providing opportunities for our students.”

“Stronger readers excel at understanding the various perspectives that may arise regarding a civic or ethical issue. They’re less likely to assume that disagreement equates to ignorance.”

Catherine Snow

The educators and researchers who engaged with the Gazette expressed differing opinions on whether Steinbeck, Fitzgerald, and Harper Lee still merit their prevalence.

“To Kill a Mockingbird,” published by Lee in 1960, could be seen as the foundational American text of the ‘white savior’ trope, Burt noted. And yes, Steinbeck was a Nobel laureate in literature, but regarding ‘Of Mice and Men,’ “the implication is that someone with cognitive disabilities is likely to commit a crime … the high school curriculum would benefit from omitting that,” Burt commented.

While Burt lauded “Gatsby” as a valuable option for many adolescents, Catherine Snow was less forgiving.

“I always disliked that book,” she stated.

Snow, a renowned literacy researcher, has recently retired from the Harvard Graduate School of Education. She contended that substantial evidence still highlights real advantages stemming from nurturing readers.

Not only do accomplished readers perform better on general knowledge assessments — but even by elementary school, Snow asserted, “superior readers excel at grasping the multiple perspectives that might arise regarding civic or moral issues. They’re less likely to think that if someone disagrees with them, it’s due to stupidity … I believe that’s rather significant.”

Interpreting a text, analyzing tone and symbolism, grasping meaning and viewpoints — it all remains beneficial. However, Snow expressed that some older texts may no longer serve as optimal teaching resources.

“You can make all of those aged texts relevant to students today,” Snow said. (True even for “Gatsby,” she quipped: “Here’s an opportunity to study some truly dull, worthless characters, and the ways they’ve deteriorated their lives.”)

“Yet,” Snow added, “a more accessible and perhaps efficient method would be to consider…

“““html

“A collection of texts that are more inherently pertinent and can be utilized to cultivate the same crucial cognitive, linguistic, and analytical abilities.”

“Harry Potter” and “The Hunger Games” also engage in “significant, fundamental, cultural motifs and ideas,” she remarked, observing that neither is “especially simple reading.”

The cultural phenomena surrounding these two series challenged a prolonged decline in recreational reading among young individuals. In view of that trend, Cirillo and others perceive an opportunity to refresh the curriculum within the margins.

For Cirillo, works by authors of color—from Toni Morrison to Junot Díaz—ought to now be considered essential, forming a “new canon” to complement the traditional one.

Burt’s primary worry, on the other hand, is the smartphone and its firm hold on our concentration. “We are currently undergoing a transformation in media stemming from a shift in technology that is—regrettably—at least half as impactful as the invention of the printing press,” Burt stated. “I despise it; it saddens me. Yet, it is not something we can simply wish away.”

Burt suggested substituting “Of Mice and Men” with Frederick Douglass’ inaugural autobiography, labeling it as “a piece of American prose that everyone should be required to read.”

Regardless of whether it can be precisely measured, English educators still assert that there is something invaluable about deep engagement in the narrative of a book. Among those sharing this view is M.G. Prezioso, a 2024 Ed School graduate currently undertaking postdoctoral research on that very subject.

In a recent scholarly article, Prezioso uncovered a reciprocal connection between frequent reading and “story-world immersion”—a positive cycle of enjoyment in reading that might reduce the dependence on external incentives.

Furthermore, her ongoing studies of elementary students in Massachusetts and Pennsylvania have revealed preliminary yet promising links between this type of immersion and proficiency in reading comprehension, as assessed by standardized testing.

However, that does not imply abandoning the existing curriculum, Prezioso stated. “There often exists this contrast between classic, canonical literature and books that are entertaining, as if canonical works cannot be engaging or dramatic or enjoyable to read.”

Prezioso was reminded of this during her surveys of high school students. What did they find most captivating? “Harry Potter,” “The Hunger Games,” Edgar Allan Poe—and “Of Mice and Men.”

“`