“`html

Health

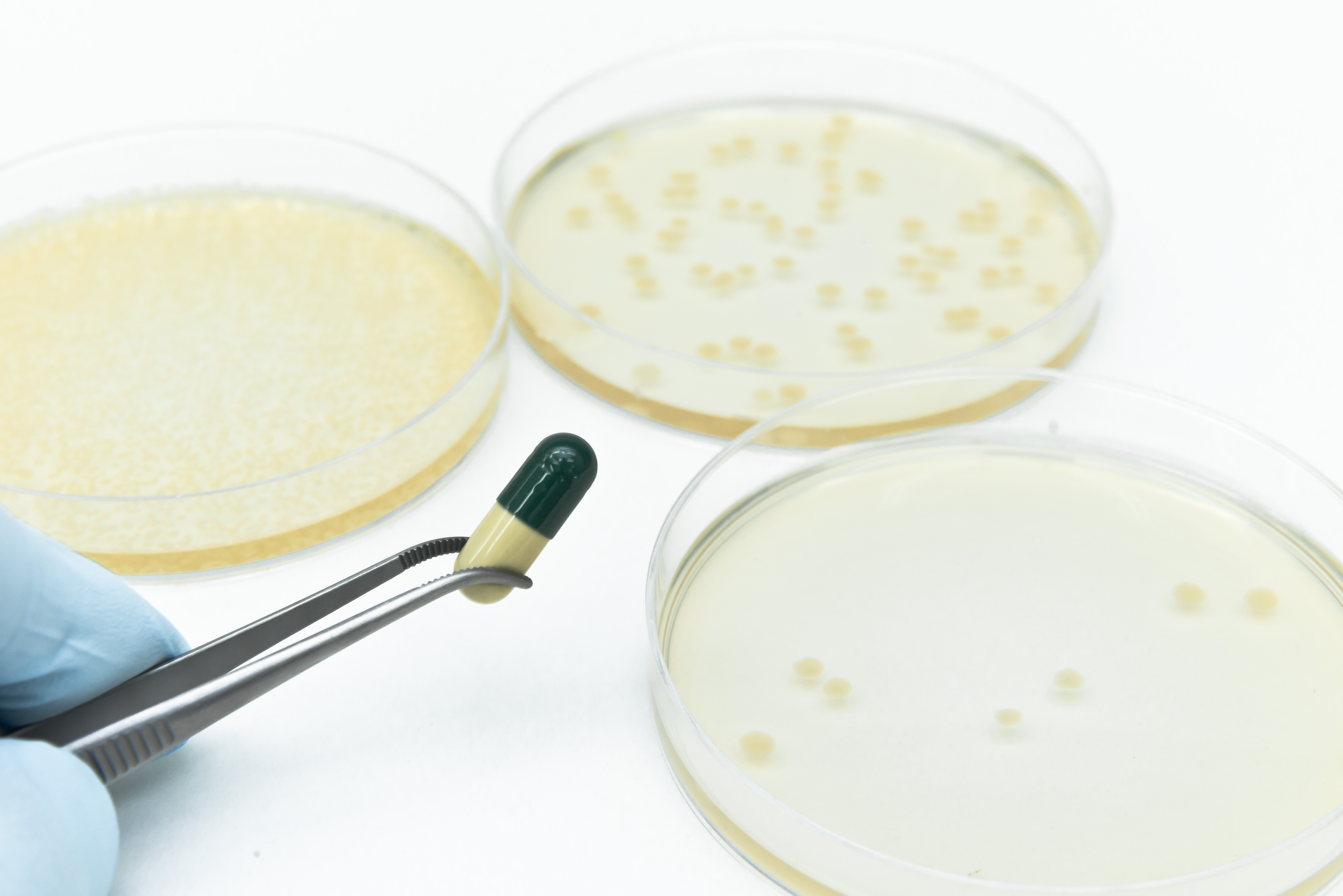

Racing against antibiotic resistance

Researchers worry that budget cuts will hinder progress in the ongoing fight against evolving bacteria

In 2023, over 2.4 million instances of syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia were identified in the U.S. While that figure is substantial, it signifies progress, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: The total number of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) dropped 1.8 percent overall from 2022 to 2023, with gonorrhea seeing the largest reduction (7.2 percent).

However, the tally of STI cases represents just one facet of the issue.

One remedy for STIs is doxycycline. It has been utilized as a preventive measure against gonorrhea, suggested as a treatment for chlamydia since 2020, and administered to manage syphilis during shortages of the preferred therapy, benzathine penicillin. Yet bacteria are living entities, and like all living organisms, they adapt. Gradually, they form resistance tactics against the antibiotics we develop to eliminate them. According to Harvard immunologist Yonatan Grad, resistance to doxycycline is escalating swiftly in the bacteria that lead to gonorrhea.

“The heightened usage of doxycycline has, as we might have anticipated, resulted in drug resistance,” Grad pointed out.

The phenomenon of bacteria evolving to counteract our most effective treatments stands as one of medicine’s core dilemmas. Since penicillin’s debut in the 1940s, antibiotics have drastically altered the landscape of medicine, extending far beyond treatments for STIs. They can eliminate the bacteria responsible for everything from urinary tract infections to meningitis to sepsis from infected wounds. Yet every antibiotic ultimately encounters the same outcome: As soon as it comes into use, bacteria begin adapting to endure it.

The scope of the challenge is daunting. Physicians prescribed 252 million antibiotic medications in 2023 in the U.S. That translates to 756 prescriptions for every 1,000 individuals, rising from 613 per 1,000 people in 2020. Per the CDC, over 2.8 million antimicrobial infections arise each year in the U.S., leading to more than 35,000 fatalities as a result of antimicrobial-resistant (AMR) infections.

“I view antibiotics as fundamental infrastructure.”

Yonatan Grad

For scientists like Grad, the relentless struggle against time can resemble a high-stakes game of Whac-a-Mole — monitoring antibiotic resistance, deciphering its mechanisms, and creating new types of medications before bacteria can catch up.

“The capacity to address these infections underpins numerous elements of medical practice — from urinary tract infections to caring for the immunocompromised, preventing surgical infections, treating them if they occur, and much more,” Grad explained. “This is core to modern clinical medicine and public health. Antibiotics serve as the foundation, the framework upon which healthcare relies.”

Should new drugs be retained or released?

Grad’s findings illustrate just how swiftly resistance can emerge. In research detailed in a July letter in the New England Journal of Medicine, Grad and colleagues examined over 14,000 genome sequences from Neisseria gonorrhoeae, the bacteria responsible for gonorrhea, uncovering that the presence of a gene conferring resistance to tetracyclines — the antibiotic class that doxycycline belongs to — skyrocketed from 10 percent in 2020 to more than 30 percent in 2024.

Fortunately, doxycycline still proves effective as a post-exposure prophylactic for syphilis and chlamydia. It remains uncertain why some pathogens exhibit a quicker development of resistance than others. The urgency differs by organism, Grad observed, with some, like Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the causative agent of tuberculosis, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, displaying “extremely drug-resistant or completely drug-resistant strains” that confront doctors with untreatable infections.

The discoveries provoke alarm bells, or at least inquiries, in medical practices across the nation: As bacteria gain resistance to established antibiotics, when is the optimal time to introduce new drugs for maximum utility before these bacteria inevitably outsmart them too? Conventional stewardship approaches have suggested withholding new medications until the older ones cease functioning. However, research from Grad’s lab in 2023 has contested that strategy. Using mathematical models to assess tactics for introducing a new antibiotic for gonorrhea, Grad discovered that the method of reserving new antibiotics led to antibiotic resistance hitting 5 percent significantly sooner than either swiftly deploying the antibiotic or using it in tandem with the…

“““html

current medication.

Lifesaving advancements stagnated

Additional time could be crucial for Amory Houghton Professor of Chemistry Andrew Myers, whose laboratory has been innovating new antibiotics, including those targeting gonorrhea, for over three decades.

“Most of the antibiotics in our ‘contemporary’ arsenal are approximately 50 years old and no longer effective against many of the pathogens emerging in healthcare facilities and even within the community,” Myers stated. “It’s a significant issue and it’s not as widely recognized as I believe it ought to be.”

“In my view, we can definitely win the battle — temporarily.”

Andrew Myers

A multitude of antibiotics function by targeting and obstructing bacterial ribosomes, the core machinery that translates the directives in RNA into a protein readout. Ribosomes are “extraordinarily intricate” 3D structures, Myers noted. Developing new antibiotics necessitates the creation of new chemical compounds that can fit like puzzle pieces into their grooves and extensions.

“My laboratory often invests considerable time, sometimes years, in developing the chemistry — inventing the chemistry — that allows us to create new members of these antibiotic categories,” Myers specified. “Then we spend years generating literally thousands of different members of the class, evaluating them. Do they eliminate bacteria? Do they eradicate bacteria that are resistant to current antibiotics? We’ve had remarkable success with this, one class of antibiotics after another. The strategy is effective.”

However, it is currently jeopardized. The Trump administration terminated a National Institutes of Health grant for Myers’ lab dedicated to developing lincosamides, a class of antibiotics whose last approved member, clindamycin, dates back to 1970. A second revoked NIH grant may jeopardize a promising new antibiotic on the verge of further development. Myers’ lab has developed a novel molecule that has demonstrated effectiveness in annihilating Klebsiella Pneumoniae and E. coli, both identified by the World Health Organization as among the highest priority pathogens. Without continued financial support, this molecule may not progress to clinical trials and may never achieve approval as a medication.

“A misconception among individuals is that these decisions can be easily reversed and these NIH grants reinstated,” Myers explained. “That’s not accurate. The damage is tangible, and in some instances, irreversible.”

Continuing Paul Farmer’s legacy

The funding cuts reach beyond individual laboratories to a global health framework. Carole Mitnick, a professor of global health and social medicine at Harvard Medical School, investigates multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) and has observed roughly 79 percent of USAID funding for global TB initiatives being slashed this year.

“In the Democratic Republic of Congo, in Sierra Leone, and likely elsewhere, we’ve witnessed stocks of lifesaving anti-TB medications lying in warehouses, expiring, due to canceled programs or staff abruptly laid off,” she remarked. “Not only is it immediately life-threatening and cruel not to provide these lifesaving treatments, but it paves the way for increased antimicrobial resistance by failing to offer complete therapies. Moreover, it clearly squanders U.S. taxpayer money to invest in the procurement of these medications only for them to expire on shelves.”

Mitnick’s research on multidrug-resistant TB, a type of antimicrobial resistance, builds upon the legacy of Paul Farmer, the late Harvard professor and co-founder of Partners In Health who transformed MDR-TB treatment by rejecting utilitarian approaches that dismissed the most vulnerable patients.

“Getting to know Paul and having him guide me, initially on my master’s thesis and ultimately on my doctoral dissertation, provided me with a new perspective,” Mitnick noted. “It empowered me to adopt a social justice framework and assert that, in fact, our research should be driven by those suffering the most. How do we combine the research, which we’re well-equipped to undertake at Harvard, with direct service aimed at reaching the populations who are most marginalized? That approach remains very much in effect and continues to influence the decisions of several researchers in our department, honoring Paul’s legacy.”

“Our research should be driven by who’s suffering the most.”

Carole Mitnick

Globally, nearly 500,000 new individuals are estimated to have MDR-TB or its even tougher counterpart, extensively drug-resistant TB, each year. MDR-TB resulted in an estimated 150,000 deaths worldwide in 2023. TB epitomizes pathogen traits and social conditions that promote the selection of drug-resistant mutants. In a singular case of TB, the bacteria population consists of bacteria at different growth phases and in various bodily environments, necessitating distinct medications that can target each of these forms. Multidrug treatment protocols are lengthy (spanning months, not days) and toxic, making adherence difficult for patients. Moreover, in the absence of incentives or requirements, there is a significant delay between developing new medications and creating tests that can detect resistance to those drugs. Consequently, treatment is often administered without any knowledge of resistance, thereby generating more resistance.

The battle against MDR-TB has an unexpected new ally: Nerdfighters, the fan community of notable video bloggers John and Hank Green — or, more precisely, a subset of that fandom identifying themselves as TBFighters. John Green’s 2024 publication, “Everything is Tuberculosis,” raised awareness regarding the prohibitive costs associated with TB diagnostic tests.

Mitnick stated that in the acknowledgments, Green referred to his book as a sort of love letter to Paul Farmer. “Paul didn’t directly introduce John to TB, but it is indeed Paul’s legacy that led John Green to Sierra Leone, where he met a young man named Henry who had multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. This experience awakened in John the realization that TB was not a relic of the past, but a pressing issue in the present.”

The TBFighters invigorated an established coalition initiative to reduce the cost of tests for TB and other diseases from approximately $10 per test to about $5 per test, based on estimates that $5 would cover production costs plus profits, even at lower sales volumes.

“It wasn’t until John Green and the TBFighters entered the scene in 2023 that we started to see progress: The manufacturer announced a reduction of about 20 percent on the price of one TB test,” Mitnick remarked. “So not an outright victory, but a partial success.”

Despite the obstacles, researchers remain cautiously hopeful. “In my opinion, we can certainly win the battle — temporarily,” asserted Myers. “Regardless of what we develop, bacteria will find a means to outsmart us. Nonetheless, I believe that the compounds we are creating could have a clinical lifespan of many decades, perhaps even as long as 100 years, if they are utilized judiciously.”

Grad envisions his work much like the crews maintaining city sidewalks or repairing bridges. “I consider antibiotics to be infrastructure,” he stated. “These resources we employ to uphold our health require ongoing investment.”

“`