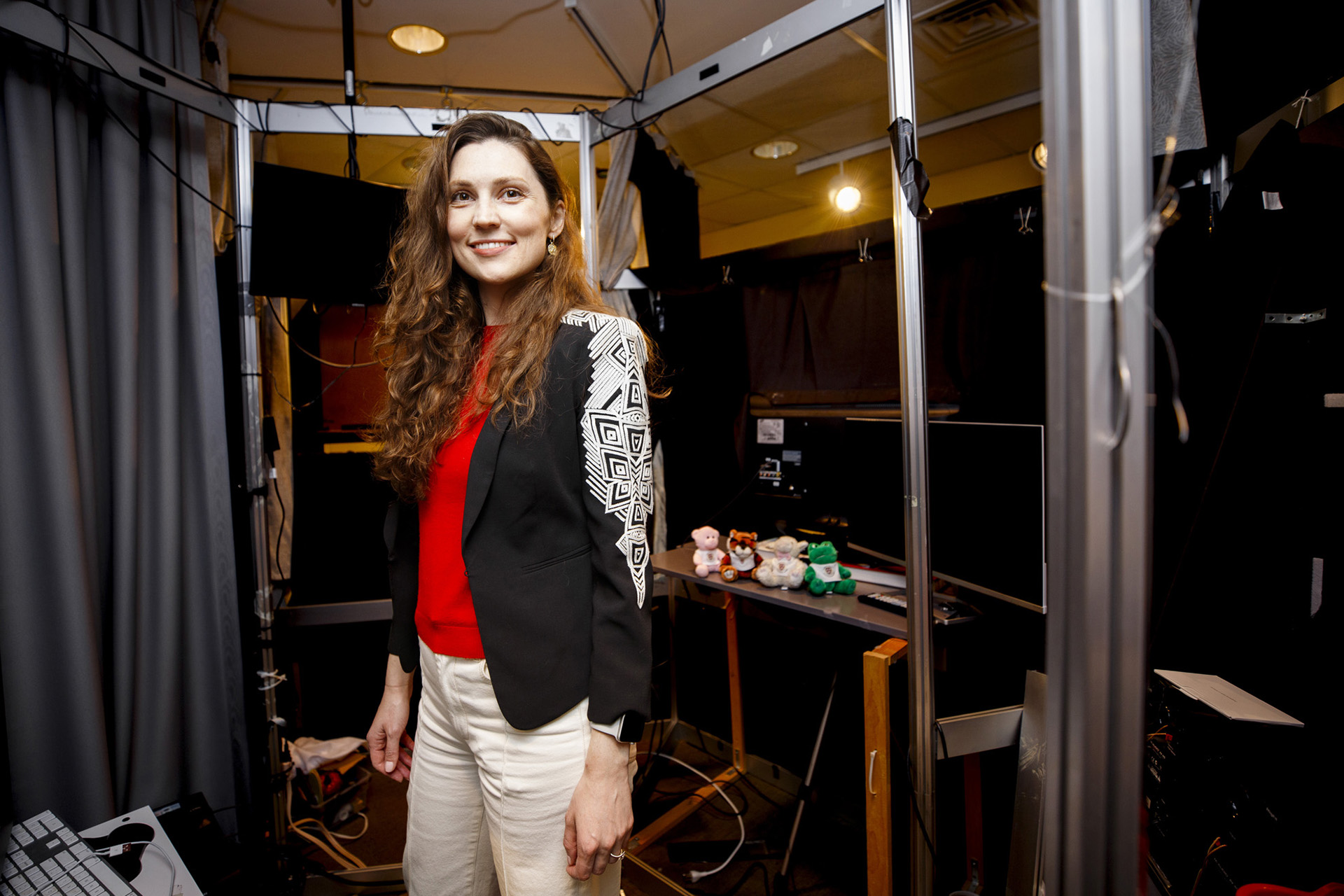

Elena Luchkina is a research scientist in the Psychology Department.

Photo by Grace DuVal

Science & Tech

Out of view but not out of thought

By 15 months, youngsters can grasp the meanings of items they’ve never encountered

Love, quantum physics, yesterday’s weather — people readily engage in conversations about these and many other things that are invisible. Infants begin to cultivate this skill early, recent studies indicate. Even infants as young as 15 months can deduce the meanings of nouns without visualizing their related objects, as demonstrated by research conducted by Elena Luchkina, a research scientist in Elizabeth Spelke’s laboratory at Harvard’s Department of Psychology, along with Sandra Waxman, a professor of psychology and the director of the Infant and Child Development Center at Northwestern University.

In this modified dialogue with the Gazette, Luchkina elaborates on how she infers what infants are contemplating, the potential of her research in addressing learning challenges, and whether the capability to discuss the unseen distinguishes us from other species.

Are humans the only creatures that converse about things they cannot perceive?

This is a contentious issue, and the answer varies based on perspective. Evidence suggests that great apes can convey ideas about absent objects, albeit in a restricted capacity. For instance, if an ape observes an object and it is quickly concealed, they might point to where they last saw it. Alternatively, they can request food not present in their vicinity. However, this differs from how we, as humans, discuss absent or invisible entities through language.

For instance, if I describe my favorite cup, I can share a wealth of details that are not discernible from its exterior, such as that my sister gifted it to me and that she purchased it at a local store. Researchers have not recorded nonhuman animals discussing hidden items or abstract ideas with such complexity.

“The ability to represent an unseen item and learn its name could be a fundamental element for discussions about more intricate abstract ideas.”

However, we do not innately possess this ability. By the time they turn one, most children can perform what apes can do — point to where they have seen objects recently, like a ball their parent just concealed. This marks a significant advancement. Nonetheless, referring to recently observed things differs from discussing invisible or abstract concepts. Typically, children acquire this skill by age 2, after which they begin to articulate thoughts about absent caregivers and future events. I aspire to comprehend how and when this ability develops.

How did you determine the age at which infants can comprehend the meanings of novel words without visualizing their corresponding items?

We are studying children who are too young to articulate more than a few words, so we monitored their eye movements to deduce their knowledge and thoughts.

During the training phase of the experiment, we displayed a video of an actress who glanced over her shoulder and named objects appearing on a screen behind her. For instance, if an apple appeared, she would exclaim, “Look, it’s an apple!” She repeated this three times, naming three items from a specific category, like fruits. The fourth instance featured an object that appeared behind her body, beyond the infant’s view. Instead of using the actual name of the fruit, she employed a nonsensical term, such as, “Look, it’s a blicket!”

Eventually, during the testing phase, a screen displayed two objects — one being a fruit we predicted would be unfamiliar to most infants in our study, such as a dragon fruit. The other was an unrelated item, like an ottoman or a car. We then instructed the infant, “Locate the blicket!,” and we monitored how long they observed each object. If an infant gazed longer at the fruit than at the unrelated item, we inferred that they recognized a blicket as a type of fruit, even without having seen it, given that the other three items were fruits.

We repeated this process several times with various object categories, and control conditions provided further assurance regarding our findings.

And what did you discover?

What intrigued us was that 15-month-olds successfully identified the blicket, while 12-month-olds did not. This may be due to 12-month-olds lacking the attention span or memory capacity required to complete the task. Alternatively, they may not have developed the ability to visualize an object they’ve never encountered, whereas 15-month-olds are sufficiently matured to achieve this.

Previous studies have suggested that infants needed to be 19-24 months old to link a word to an unseen object. Thus, we discovered that infants possess this capability at a younger age than previously assumed.

In your paper, you draw a parallel between an infant’s skill in identifying the blicket and an adult’s capacity to discuss complex concepts like justice or the square root of negative one. What’s the link?

Indeed — the infants won’t be discussing imaginary numbers anytime soon. However, the capacity to signify an unseen entity and learn its name might be a foundational aspect for conversing about more advanced abstract ideas. Similar to adults, infants in our research are formulating mental images of things they currently cannot see and actively associating words with them.

What’s next for this study?

We aim to determine whether infants who excel at locating the blicket at 15 months are also the most adept at acquiring language alone by 24 months. If this is true, it could indicate that an early skill in understanding unseen objects provides infants with a crucial basis for future language learning.

What potential applications might this research have?

If infants who excel in our task at 15 months also demonstrate enhanced language acquisition at 24 months — and this relationship is genuinely due to their language learning ability and not influenced by other factors like memory or attention — then the find-the-blicket task could serve as a diagnostic measure for language learning challenges. Early identification of these issues could enable us to create interventions that address these difficulties before they escalate in educational settings.

The research described in this article received funding from the National Institutes of Health.