Country & Globe

Number of individuals impacted by rental affordability reaches unprecedented levels

Public policy specialist discusses potential solutions to alleviate expenses during national housing crisis

In the midst of a nationwide housing deficit, a new report reveals that the number of individuals affected by rental affordability has reached an unprecedented peak.

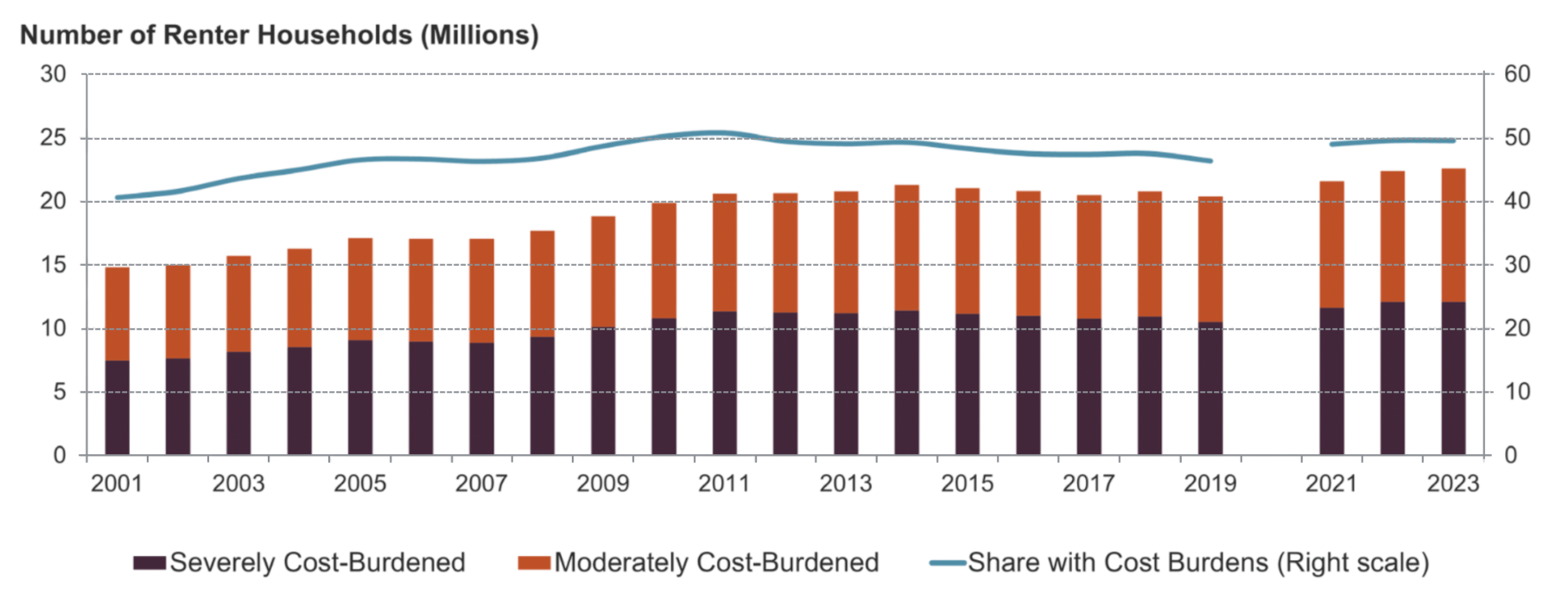

As of 2023, 22.6 million rental households allocated over 30 percent of their income to rent and utilities, marking an increase of 2.2 million since 2019. More than half, or 12.1 million, dedicated over 50 percent of their income to housing expenses, according to recent studies from the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard.

The deteriorating affordability impacts renters across various income brackets. Middle-income renters, earning between $30,000-$75,000, accounted for 41 percent of all cost-burdened households in 2023. Those with incomes of $75,000 or more represented 9 percent. Holding a full-time position does not guarantee that housing will remain affordable. In fact, 36 percent of fully employed renters faced cost burdens in 2023.

In this revised dialogue, Chris Herbert, the center’s director, elaborates on why renting is becoming increasingly unaffordable and what measures cities can consider adopting.

The count of households grappling with housing expenses is at a historic high. What factors contribute to this?

There are two primary reasons. Following 2021, we observed rents escalating at double-digit rates in the immediate wake of the pandemic. By 2023, growth began to decelerate. In 2024, it was increasing at more typical inflation rates, indicating improvement. This was due to exceptionally strong demand stemming from the pandemic. Supply was unable to keep pace, resulting in skyrocketing rents.

This came on the heels of two decades marked by declining affordability. A concealed affordability crisis was developing, reflected in the number of renters facing cost burdens.

After the Great Recession, around 2011, we reached a peak in both the number and percentage of renters burdened by costs. Subsequently, conditions improved slightly.

However, beneath the surface, while the overall proportion of cost-burdened renters was declining, there was a notable increase in the percentage of renters working full-time year-round, in positions that were decent but not remarkable, who were still facing cost burdens.

The essence of the issue was that the challenges of housing affordability were spreading beyond just the poorest households to include more working individuals, particularly the youth.

The crisis worsened significantly since the pandemic, but it had already been on the rise, particularly affecting those in employment.

The total of cost-burdened renters has reached yet another unprecedented high

An increasing number of middle- and higher-income renters are facing challenges with housing expenses. What explains this shift?

That’s a pressing question. The most frequent response is that we haven’t constructed enough housing units. To some extent, that holds true. Multifamily vacancy rates became considerably tight, especially in light of the pandemic surge. Thus, there was a prevailing belief that we lacked sufficient apartment availability.

That constitutes part of the narrative, but we often place too much emphasis on it. The other aspect is that the expense of constructing housing units is exceedingly high. There’s a perception that “building more homes will lower prices.” However, it’s important to remember that developers will only build housing if it is financially viable for them.

The expenses fall into four major categories: There’s land costs, which has been a focal point of discussions around zoning and the scarcity of land designated for high-density housing. Then there are construction expenses — these account for 60 percent of the total apartment building cost. Conversely, land generally comprises only 20 percent. Additionally, there are soft costs, such as architectural and engineering expenses, as well as financing fees. The latter increase amid complicated approval processes. These costs typically range from 10-15 percent of the total, thus not significantly impacting overall prices. However, soaring financing costs, particularly when interest rates rise to 7 percent, play a major role.

Housing affordability is impacted by a multitude of factors, including zoning regulations, construction costs, a lack of advancements in construction efficiency, and the intricacies of the approval process alongside elevated capital costs.

Boston mayoral candidates Josh Kraft and Mayor Michelle Wu have indicated that housing affordability will be a critical issue in the forthcoming election. Do mayors and cities possess effective strategies to lower housing expenses?

There has been extensive discussion regarding regulatory frameworks. How stringent is your zoning? How burdensome is the approval process? How challenging is it for a developer to propose a reasonably-scaled project and have it accepted and constructed? A significant undertaking cities are pursuing involves reassessing their zoning laws. Cambridge has explored various versions of these regulations.

Relating to that is the approval process: The affordable housing overlay in Cambridge stipulates that if a proposed development satisfies certain criteria concerning setbacks, density, and other factors, it will receive approval without undergoing a full design review process. Thus, cities can adopt such measures.

How does this impact affordability? It diminishes soft costs. To the degree that you are permitting more density, it might enable better land value. The complication arises because land value is dependent on the number of units that can be accommodated. Thus, if you indicate that only two units can be built, and the land was…“`html

valued, let’s say, at a million dollars, and then you mention, “Now you can add 10 units to it.” That translates to $100,000 per unit. I’ve just conserved a significant amount of cash.

However, the moment you inform a developer that you can include 10 units, the developer exclaims, “I’ll pay 5 million dollars for that parcel of land.” Consequently, your savings from the added density are diminished. All cities can attempt in this respect is to minimize friction and alleviate pressure on prices to escalate more rapidly than they otherwise would.

You’ll face considerable challenges addressing the affordability dilemma through zoning. If you’re discussing lower-income families or even moderately-income households, you’ll need to consider strategies to subsidize the expense of that housing. This means municipalities must discover methods to acquire funds.

Boston has excelled in linkage payments for commercial construction, generating a substantial amount of revenue, as has Cambridge, along with an affordable housing trust that benefits from those funds. They can allocate some general appropriations from their budget.

You can also explore unique tax measures. Boston proposed a transfer tax that former Mayor Marty Walsh estimated would yield about $100 million annually for the Affordable Housing Trust. Mayor Wu pursued this initiative, but the state legislature has impeded their efforts.

A significant challenge for cities is determining how to secure additional financial resources to assist in subsidizing housing. One approach cities can take is to compile an inventory of all the land they possess. That land could serve as a vital subsidy. Boston has been working on this.

“A significant challenge for cities is determining how to secure additional financial resources to assist in subsidizing housing. One approach cities can take is to compile an inventory of all the land they possess. That land could serve as a vital subsidy. Boston has been working on this.”

Chris Herbert

And perhaps encourage creativity in housing design. Boston’s Housing Innovation Lab has been examining how to increase modular housing, enhance factory production efficiencies, and how the City of Boston can contribute to scaling this up.

Are there any promising policy strategies or favorable trends emerging?

We are undoubtedly in a scenario where experimentation is essential. There is a significant degree of trial and error occurring. There’s a provision in the Massachusetts state bond bill for a revolving loan fund. People have come to recognize that housing affordability has been a persistent issue that has developed over a long period, necessitating a long-term vision to tackle it.

A major factor in the appreciation of housing values is the inflation of land prices. Properties depreciate, thus a house erected in 2000 should hold less value today. However, housing prices in this area have doubled since 2000, primarily due to the land value. It is the land values that capture a significant portion of the inflation in housing costs. A solution is to secure long-term land ownership to prevent that inflation from impacting the residents of the home.

The other aspect is that if [property owners] operate housing at cost, then you can begin to charge rents that are considerably more reasonable. When combined with public or nonprofit ownership that might benefit from exemption or limitations on property taxes, low-cost land, at-cost rents, and reduced expenses stemming from lower property taxes, you can begin to develop housing that remains affordable.

“`