“`html

Country & Globe

‘Now I have transformed into death, the annihilator of the realms’

Oral accounts provide a multifaceted perspective of anxiety and solace, optimism and apprehension at the atomic bomb test 80 years prior.

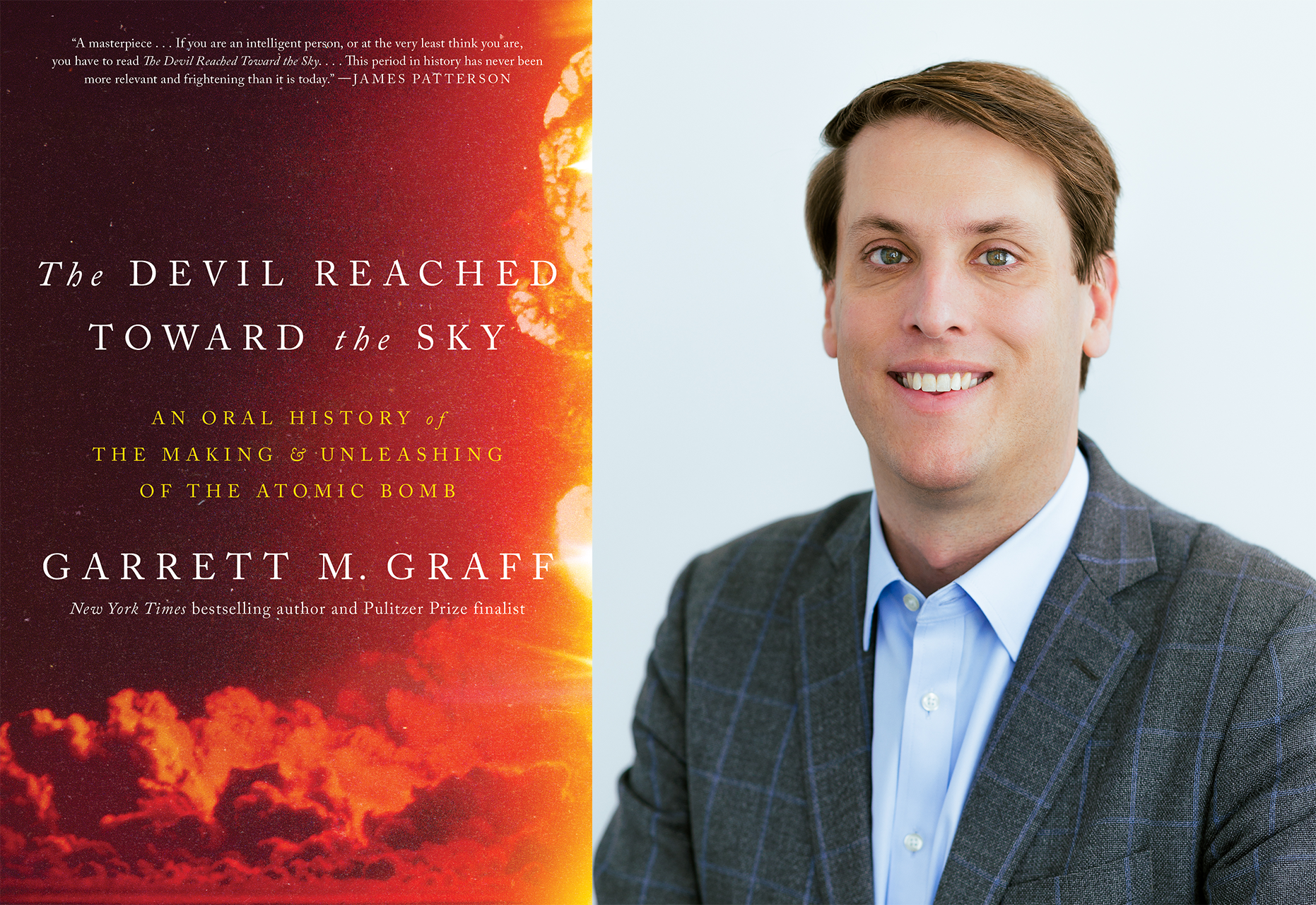

Excerpted from “The Devil Reached Toward the Sky: An Oral History of the Creation and Release of the Atomic Bomb” by Garrett M. Graff ’03.

Wisconsin physicist Joseph O. Hirschfelder: It was the moment to prepare for the detonation. There were 300 of us gathered at our station. This group consisted of military personnel, researchers, visiting officials, etc. We were all chilly, fatigued, and extremely anxious. Most of us walked back and forth. Each of us had been provided with specially darkened glasses to witness the blast.

Rice physicist Hugh T. Richards: I was stationed at Base Camp, 9.7 miles from ground zero. The test was planned for 2:00 a.m. on July 16. However, a severe thunderstorm struck the camp area around that time, and upon the meteorologist’s recommendation, the experiment was delayed until 5:30 a.m. to allow the inclement weather to clear.

Harvard chemistry professor George B. Kistiakowsky: Everything was primed for ignition. Just before the countdown hit zero, I ascended to the top of the control bunker, donned dark glasses, and turned away from the tower. I was fairly convinced that the physicists were overstating the nuclear implications of what was about to occur. Well, I was mistaken.

Brig. Gen. Thomas F. Farrell, Manhattan Project field operations chief: Dr. [J. Robert] Oppenheimer held onto a post to steady himself. In the final seconds, he gazed straight ahead.

Maj. Gen. Leslie Groves, Manhattan Project director: The explosion occurred exactly at the zero count on July 16, 1945.

Trinity test site director Kenneth T. Bainbridge: The bomb exploded at 5:29:45 a.m.

Farrell: In that fleeting moment in the isolated New Mexico desert, the incredible effort of the intellects and muscle of all these individuals culminated abruptly and astonishingly.

Los Alamos physicist Robert Christy: Oh, it was a theatrical event!

The bomb’s core is loaded into a vehicle at the Army-owned McDonald ranch house, where it was assembled, to be taken to the nearby firing tower at the test site.

US Department of Energy, Historian’s Office

Los Alamos technician Val L. Fitch: It took about 30 millionths of a second for the light from the blast to reach us outside the bunker at S-10.

N.Y. Times reporter William L. Laurence: From deep within the earth, a light emerged not of this realm, the radiance of numerous suns combined.

Hirschfelder: Suddenly, the night transformed into day.

Groves: My initial impression was one of colossal brightness.

Physicist Warren Nyer: The most dazzling flash imaginable.

British physicist Otto R. Frisch: Without any sound, it appeared as if the sun was shining—or so it seemed. The sandy dunes at the desert’s edge sparkled in a blinding light, nearly colorless and formless. This illumination seemed to remain constant for a couple of seconds before beginning to fade.

Nuclear physicist and radio chemist Emilio Segrè: Indeed, in a fleeting fraction of a second, that brightness, at our distance from the detonation, could inflict a worse sunburn than an entire day under a sunny shoreline. A thought crossed my mind that perhaps the atmosphere was igniting, signaling the world’s end, although I knew that this possibility had been thoroughly examined and dismissed.

British physicist Rudolf Peierls: We had been aware of what to anticipate, but no degree of imagination could provide us with a hint of the actual experience.

Physicist Richard P. Feynman: This massive flash, so blinding that I ducked.

Los Alamos physicist Joan Hinton: It was akin to being at the base of a vast ocean of light. We were enveloped in it from every direction.

Los Alamos physicist Marvin H. Wilkening: It was reminiscent of being near an old-fashioned camera flash. If you were close enough, the warmth could be felt from the intense illumination, and the light from the explosion reflecting off the mountains and clouds was sufficiently intense to be perceived.

Bainbridge: I sensed the warmth on the back of my neck, uncomfortably hot.

Richards: Though I was turned away from ground zero, it felt like someone had slapped my face.

Kistiakowsky: I am certain that at the edge of the world—in the final millisecond of the earth’s existence—the last individual will witness what we have just experienced.

Nyer: I immediately recognized that the entire operation had succeeded.

Physicist Lawrence H. Johnston: At the zero count, we released our parachute gauges. There was a flash as the bomb detonated, and we braced ourselves for the shock wave to reach our microphones hanging in the air from the parachutes for documentation. The flash was remarkably brilliant, even at 20 miles. The white light illuminated the interior of our aircraft, dimmed to orange, and then vanished. My immediate thought was, “Thank goodness, my detonators functioned!”

Hinton: The light seemed to retract into the bomb as if it were being drawn in.

Groves: Then as I pivoted, I beheld the now-familiar fireball.

Los Alamos physicist Boyce McDaniel: The radiant flash of an expanding sphere was succeeded by the billowing flame of an orange orb ascending above the plain.

Frisch:

“““html

The entity on the skyline, resembling a tiny sun, remained excessively bright to gaze upon. I continued to blink and attempt to catch a glimpse, and after approximately another 10 seconds, it had expanded and softened into something resembling a colossal oil blaze, with a shape that evoked the image of a strawberry. It was gradually ascending into the firmament from the earth, tethered by a lengthening gray stalk of swirling dust; oddly, I envisioned a searing elephant balanced upright on its trunk.

Farrell: Oppenheimer’s countenance relaxed into a look of immense relief.

Laurence: I positioned myself beside [physics Nobel laureate] Professor [James] Chadwick at the pivotal moment for the neutron. Never before had a man been witness to his own discovery manifesting so profoundly upon the fate of humanity, both in the immediate term and for all future generations. The minuscule neutron, which the world initially overlooked upon its discovery, had cast its influence over the entire globe and its denizens. He grunted, leapt lightly into the air, and paused once more.

Groves: As [Vannevar] Bush [director of the Office of Scientific Research and Development], [Harvard President James] Conant, and I sat on the ground observing this spectacle, our first responses were exchanged silently through handshake. We all stood, ensuring that by the time the shock wave reached us, we were upright.

Fitch: The blast wave approached in about 30 seconds. There was an initial loud bang, a sharp rush of air, and then a prolonged period of reverberation as the sound waves resonated off nearby peaks and returned to us.

Laurence: From the vast silence emerged a tremendous thunder.

Los Alamos theoretical physicist Edward Teller: Bill Laurence startled and inquired, “What was that?” It was, naturally, the sound of the explosion. The sound waves had taken a couple of minutes to reach our location, 20 miles away.

Frisch: The explosion’s sound arrived minutes later, quite loud despite having covered my ears, accompanied by a continuous rumble akin to distant heavy traffic. I can still recall it.

Princeton physicist Robert R. Wilson: The memory I retain is from the moment I removed the dark glasses; I observed a spectrum of colors surrounding me and the sky illuminated by radiation—it was a shade of purple, reminiscent of aurora borealis light, with a massive balloon-like entity expanding upwards. Yet the scale was striking. There was this vast desert nearby, but it made the mountains appear diminutive.

Laurence: For a brief moment, the color was an otherworldly green, akin to that witnessed only in the sun’s corona during a total eclipse. As if the earth had split open and the heavens had torn apart.

Hirschfelder: The fireball gradually transformed from white to yellow to red as it expanded and ascended; after about five seconds, darkness returned but the sky and air were filled with a purple luminescence, as if we were enveloped by an aurora borealis. For several minutes, we could trace the clouds containing radioactivity as they continued to glow with strands of this ethereal purple.

Christy: It was breathtaking. It simply grew larger and larger, eventually turning purple.

Hinton: It shifted to purple and blue and kept ascending. We were still conversing in whispers when the cloud reached a height where it was illuminated by the rising sunlight, dispersing the natural clouds. We observed a cloud that was dark red at the base while the top was bathed in daylight. Then, suddenly, the sound reached us. It was distinctly sharp and rumbled, and all of the mountains echoed with it. We abruptly began speaking aloud, feeling exposed to the entire world.

Hirschfelder: There were no skeptics present for this magnificent display. Each, in their own fashion, understood that a higher power had communicated.

Groves: Unbeknownst to me, and likely to everyone, [Nobel laureate physicist Enrico] Fermi was poised to measure the blast using a very simple apparatus.

Physicist Herbert L. Anderson: Fermi later recounted that he did not hear the explosion’s sound due to his intense focus on the straightforward experiment he was conducting: he dropped small pieces of paper and observed their descent.

Groves: There was no ground breeze; thus, when the shock wave hit, it sent some scraps flying several feet away.

Anderson: When the explosion’s blast struck them, it pulled them along, and they fell to the ground at some distance. He measured this distance and utilized the result to estimate the explosion’s power.

Groves: He was remarkably accurate in his calculations compared to those made later from the data gathered by our intricate instruments.

Hirschfelder: Fermi’s paper strip indicated that, in alignment with the theoretical predictions, the energy yield of the atomic bomb was equivalent to 20,000 tons of TNT. Professor [Isidor] Rabi, a frequent visitor to Los Alamos, won the wager on the energy yield—he relied on the calculations from the Theoretical Division! None of us dared to make such a prediction, aware of all the estimations involved in the calculations and the immense accuracy required in the bomb’s fabrication.

Optical engineer and photographer Berlyn Brixner: The bomb had surpassed our highest expectations.

Bainbridge: I experienced a sense of exhilaration that the “gadget” had functioned correctly, followed by profound relief. I rose from the ground to congratulate Oppenheimer and others on the success of the implosion technique. I concluded by saying to Robert, “Now we are all sons of bitches.” Years later, he recalled my remark and stated to me, “We do not need to clarify them for anyone.” I believe I will always honor his statement, even though some imaginative individuals fail to place the remark in context and grasp its full meaning. Oppenheimer told my younger daughter in 1966 that it was the best thing anyone said following the test.

Chicago physics graduate student Leona H. Woods: The illumination from Trinity was visible in towns as far as 180 miles away.

Physicist Luis Alvarez: Arthur Compton recounted that a woman visited him after the war to express thanks for restoring her family’s faith in her sanity. She had been visiting her daughter in Los Angeles and was driving home across New Mexico early one morning to evade the midday heat. She informed her family that she had witnessed the sun rise in the east, set, and then reappear at the usual time for sunrise. Everyone was convinced that Grandma had lost her marbles until the report of the Trinity blast was published in the newspapers on August 4, 1945.

Elsie McMillan: [At home in Los Alamos,] I had to attempt to get more rest. There was a soft knock at my door. There stood Lois Bradbury, my friend and neighbor. She was aware. Her husband [physicist Norris] was out there too. She remarked that her children were asleep and would be all right since she was nearby and could check on them periodically. “Please, can’t we stay together this long night?” she implored. We discussed numerous subjects, our men, whom we cherished deeply, our children’s futures, and the war with all its horrors. Lois peered out of the window. It was

“““html

5:15 a.m. and we started to ponder. Had climatic circumstances been incorrect? Had it turned out to be a flop? I sat by the window nursing [physicist] Ed’s and my infant. Lois was gazing outside. There was an overwhelming stillness in that space. Abruptly, a blaze erupted and the entire sky became illuminated. The clock showed 5:30 a.m. The baby remained oblivious. We were too apprehensive and astonished to utter a word. We exchanged glances. It was a triumph.

Woods: The primary task assigned to Herb was to assess the yield of the Trinity test of the plutonium bomb. Herb modified several Army tanks with robust steel armor to venture into the desert following the Trinity explosion to collect surface dirt samples. After the successful detonation at Trinity, the tanks collected desert soil now transformed into glass, incorporating and also covered with fallout.

Anderson: The technique functioned effectively. The outcome held significant value. It aided in determining the altitude at which the bomb ought to be detonated.

Farrell: Everyone seemed to feel they had witnessed the dawn of a new era.

Los Alamos Director J. Robert Oppenheimer: We understood the world would never be the same. A few individuals chuckled, a few shed tears. Most remained silent. I recalled the passage from the Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad-Gita; Vishnu [a key Hindu god] is endeavoring to convince the prince that he must fulfill his duty, and to emphasize this, assumes his multi-armed form and declares, “Now I have become death, the destroyer of the worlds.” I suspect we all considered that, in some form or another.

Kistiakowsky: I patted Oppenheimer on the back and remarked, “Oppie, you owe me $10” because during that anxious time when I was branded as the world’s most formidable villain, who would be eternally cursed by the physicists for jeopardizing the project, I told Oppenheimer, “I wager my entire month’s pay against $10 that implosion will succeed.” I still possess that bill, bearing Oppenheimer’s signature.

Groves: Soon after the explosion, Farrell and Oppenheimer returned via jeep to the base camp, accompanied by several others who had been at the dugout. Upon meeting me, Farrell’s initial words were, “The war is concluded.” I replied, “Yes, after we drop two bombs on Japan.” I quietly congratulated Oppenheimer with “I take pride in all of you,” to which he simply responded, “Thank you.” I am certain we were both already contemplating the future.

Oppenheimer: It was a triumph.

Hirschfelder: If atomic bombs were viable, then we were relieved that it was us, not our adversaries, who had prevailed.

Teller: As the sun emerged on July 16, some of the most atrocious felonies of contemporary history—the Holocaust and its extermination camps, the obliteration of Hamburg, Dresden, and Tokyo by incendiary bombing, and all the personal brutality of conflicts around the globe—were already widely recognized. Even without an atomic bomb, 1945 would have capped a period marked by the worst human rights violations in modern history. People still inquire, with the benefit of hindsight: “Didn’t you comprehend what you were doing while working on the atomic bomb?” My response is that I don’t think any of us involved in the bomb were entirely devoid of thoughts regarding its potential repercussions. However, I would add: How could anyone who lived through that year examine the issue of the atomic bomb’s impacts without considering numerous other dilemmas? The year 1945 was a complex tapestry of events and issues, many of significant emotional weight, few directly related, all juxtaposed. Where is the individual capable of extracting a rational lesson or a moral conclusion from the diverse incidents that unfolded around the conclusion of World War II?

Cmdr. Norris Bradbury, physicist and leader of E-5, the Implosion Experimentation Group: Some individuals assert they contemplated at the time the future of humanity. I didn’t. We were engaged in war, and the blasted thing functioned.

Copyright © 2025. Reprinted by permission of Avid Reader Press, an Imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

“`