Nation & World

Want to increase the population? Motivate fathers to engage more at home.

New historical research by economist Claudia Goldin uncovers connection between birth rates and gender roles

Birth rates have decreased everywhere except sub-Saharan Africa. Furthermore, they have diminished more swiftly and further in certain developed countries than in others.

In a recent publication, Claudia Goldin, the Henry Lee Professor of Economics, clarifies this discrepancy with a data-driven model illustrating gendered and generational tensions that emerge amid rapid economic shifts. The 2023 Nobel laureate points out that countries whose economies progressed gradually throughout the 20th century — such as the U.S. and Sweden — now have an average of approximately 1.7 children per woman. In contrast, late developers like Japan, Korea, and Italy have far lower averages.

The research demonstrates how women in evolving modern economies can encounter significant disadvantages due to conventional gender expectations. “Rearing children requires time, and that time isn’t easily outsourced or mechanized,” noted Goldin in a presentation of her findings at the European Central Bank’s Annual Research Conference last autumn. “Consequently, a significant portion of the changes in fertility will hinge on whether males take on more responsibilities at home as females enter the workforce, especially if there are children in the household.”

“If they don’t,” she continued, “women will have to make sacrifices.”

Claudia Goldin.

File photo by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Her analysis builds on discoveries from a 2009 article published in the Journal of Economic Perspectives entitled “Will the Stork Return to Europe and Japan?” This paper — authored by economists James Feyrer, Bruce I. Sacerdote, Ph.D. ’97, and Ariel Dora Stern, Ph.D. ’14 — found that birth rates are highest in nations with lower income levels and minimal female employment. However, an unexpected trend was noted in wealthier nations.

“They observe that women’s involvement in the workforce is actually higher in countries with elevated fertility,” stated Goldin, who is also the Lee and Ezpeleta Professor of Arts and Sciences.

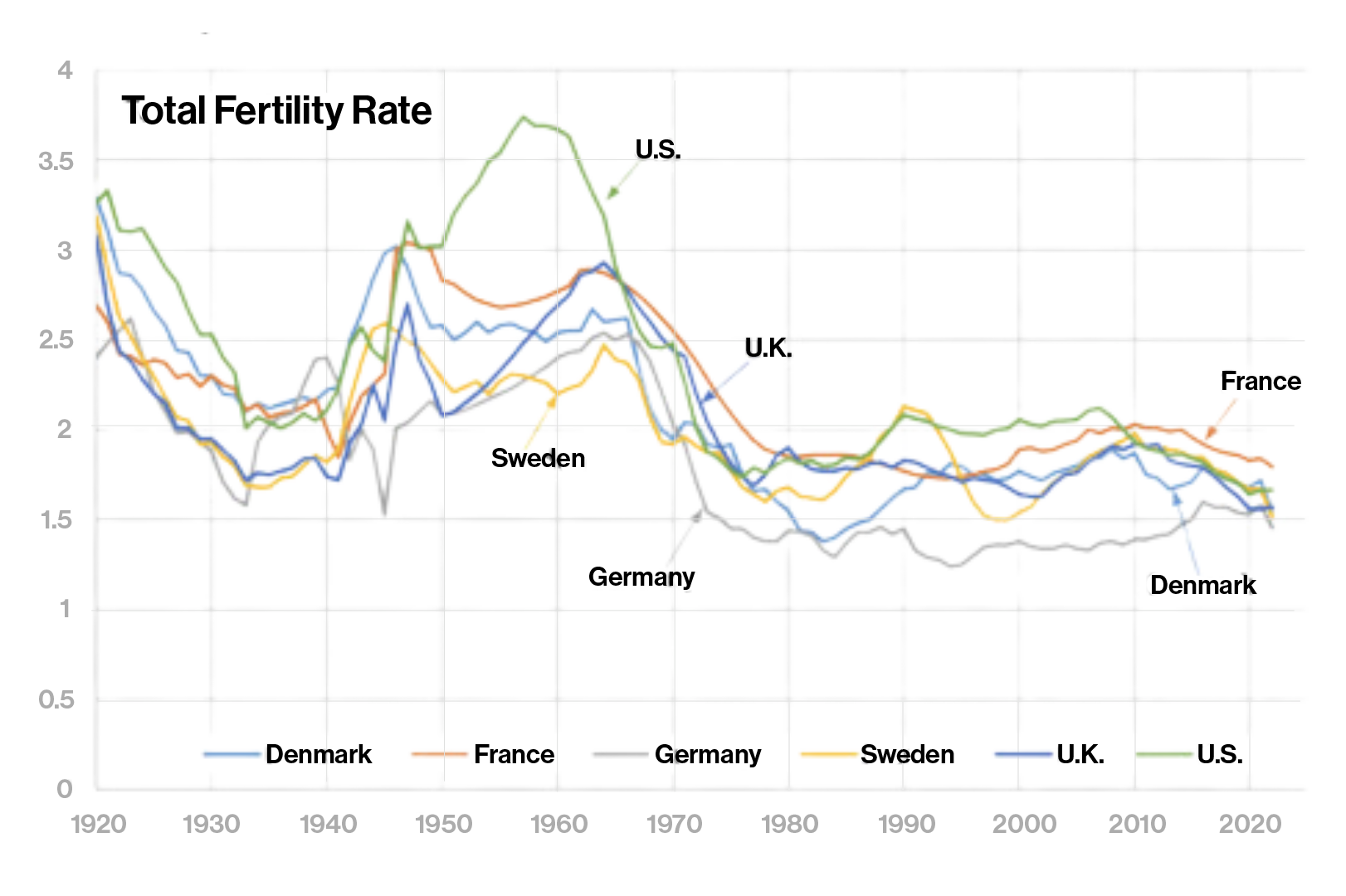

Her document contrasts birth rates in two clusters of six nations. The first cluster — consisting of Denmark, France, Germany, Sweden, the U.K., and the U.S. — experienced relatively consistent economic advancement over the 20th century, notwithstanding the disruptions caused by the Great Depression and two global conflicts. By the 1970s, all had achieved a total fertility rate of roughly two children per woman. It wasn’t until the 2010s that rates fell below that threshold.

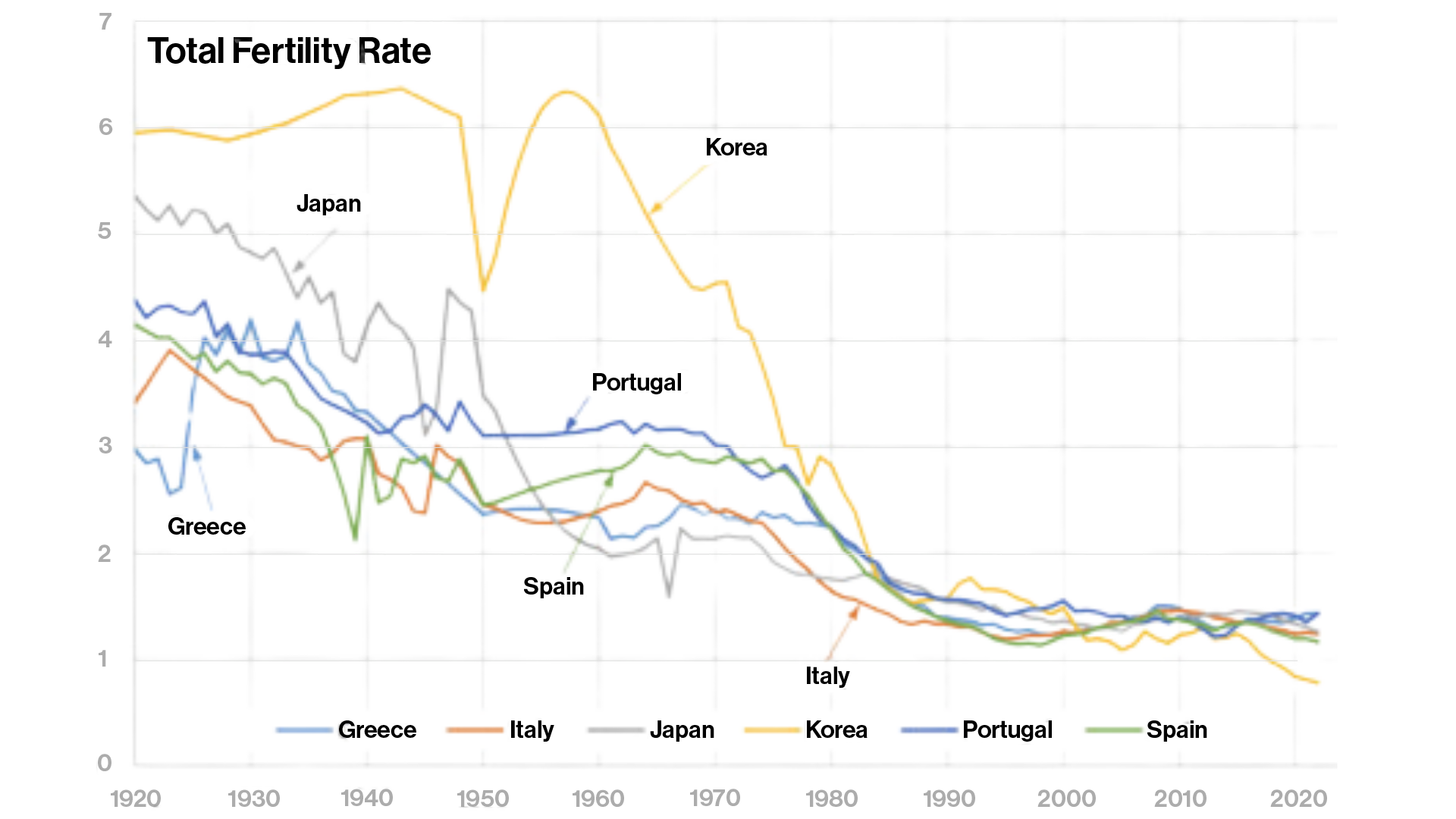

The second cluster — Greece, Italy, Japan, Korea, Portugal, and Spain — saw rapid development from the mid-1950s and ’60s after extended periods of economic stagnation or decline. Each averaged three children or more per woman in 1970. Yet all six had dropped below two by the mid-1980s, with many converging around 1.3 by the mid-1990s, Korea being the most extreme case. Its total fertility rate for 2022 (the final year included in Goldin’s examination) was 0.78 children per woman.

Demographers have labeled the fertility rates of those nations as “lowest-low.”

Total fertility rates for two sets of countries, 1920 to 2022

Goldin speculated that families in the second group of nations were “propelled” into the contemporary economy, with insufficient time to adapt gender norms. For instance, Korea witnessed income levels quadruple from the 1960s to the 1980s, while 30 percent of the population transitioned from rural to urban areas (typically Seoul) during the same timeframe.

“Rapid economic transformation frequently contests deeply entrenched beliefs,” she concluded. “And beliefs evolve more slowly than economies.”

Her study proposes a framework for comprehending how such conflicts contribute to reduced fertility. It posits that family customs and beliefs shape an individual’s fertility aspirations. However, economic circumstances experienced in early adulthood also play a significant role. When couples determine family size, men tend to place greater emphasis on traditional factors while women act as “agents of change” by prioritizing economic independence.

“It’s not that boys are more traditional than girls; it’s that boys have more advantages in a conventional household,” Goldin remarked. “Yet girls suddenly recognize that their opportunities have shifted. They can pursue education. They can join the workforce.”

Goldin’s framework indicates that an increase in macroeconomic development from childhood to adulthood generates greater generational tensions and broader divides between men’s and women’s ideal family sizes. It suggests that men who contribute more at home have a stronger influence on family size. However, when caregiving and other domestic responsibilities predominantly fall on women, their desires prevail.

Goldin’s framework indicates that greater macroeconomic development from childhood to adulthood generates greater generational tensions and broader divides between men’s and women’s ideal family sizes.

To validate her hypotheses, Goldin utilized a century’s worth of economic and geographic data from all 12 nations. Indeed, the “lowest-low” countries saw explosive growth in per-capita gross domestic product alongside significant rural-to-urban migration starting in the mid-20th century. Meanwhile, GDP showed a gradual, steady rise in the first cluster of nations, with significantly fewer migrations to major urban centers.

Time-use surveys, compiled by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, provided Goldin with insights into gendered divisions of unwaged caregiving and household labor between 2009 and 2019. She discovered a larger disparity between men and women in the “lowest-low” countries. Women spent an average of 3.1 additional hours per day on household responsibilities in Japan and three more hours per day in Italy. In comparison, in the U.S., women contributed about 1.79 more daily hours towards household tasks, while in Sweden, the difference was merely 0.8 hours.

“The crux of the matter is,” Goldin stated, “countries that experienced this exceptionally rapid rise in living standards are likely at sub-optimal birth rates.”

The labor economist and economic historian concludes by proposing an innovative solution. The U.S. baby boom, which reached more than 3.5 children per woman in the late 1950s, stands as the rare instance of an affluent nation temporarily boosting its fertility rate. This was achieved through “celebrating marriage, motherhood, the ‘ideal wife,’ and the household,” writes Goldin.

She suggests that societies aiming to promote larger families today should consider exalting fatherhood.