“`html

As scientists advance in their comprehension of the progression of Alzheimer’s disease, there are increasing chances for healthy research participants to discover their potential risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease dementia in the future. Although numerous organizations frequently encourage researchers to disclose risk predictions to individual participants, ethical dilemmas arise, as there are currently no medical treatments available to alter that risk.

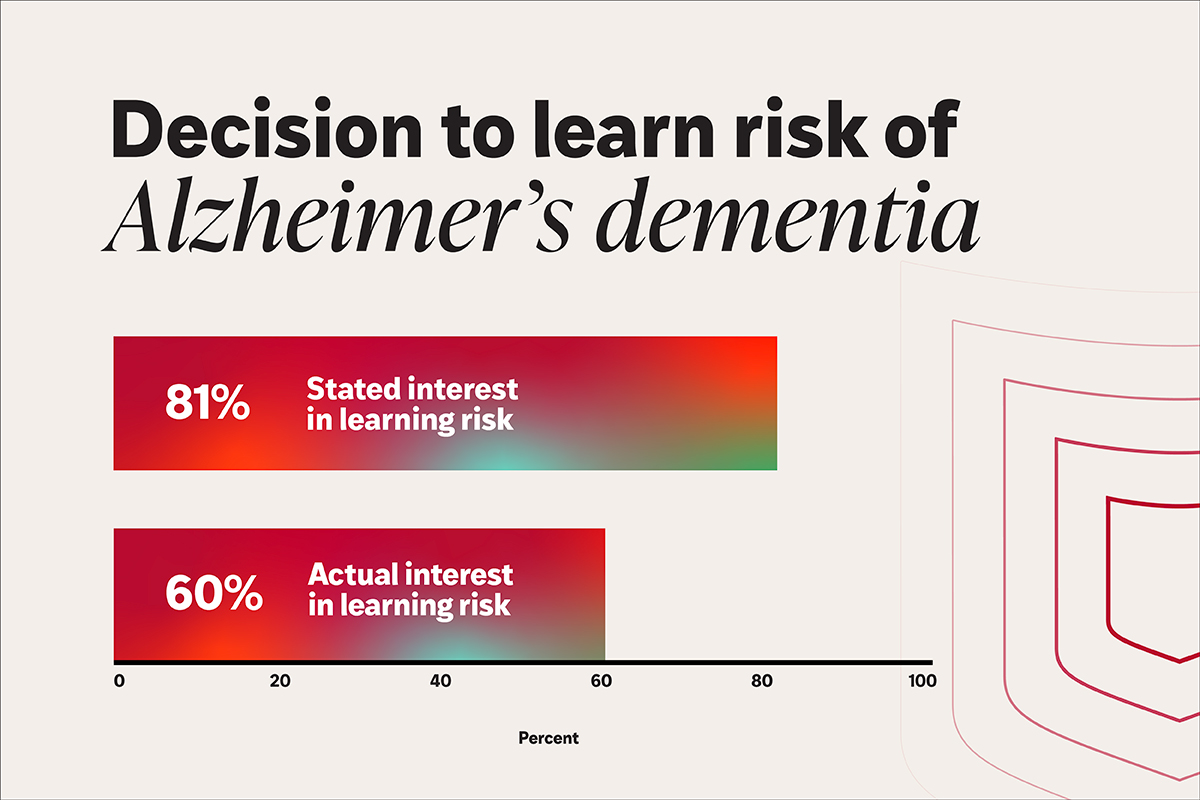

A recent investigation from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis explores the decisions healthy research volunteers make when presented with the option to ascertain their risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease dementia. The researchers observed a significant disparity between the proportion of participants expressing a desire to know their risk if such predictions were accessible and the percentage who chose to pursue those results when granted the genuine opportunity.

This insight could assist researchers in formulating studies that provide the choice of receiving results in manners that do not pressure participants into favoring one option over another. The research also underscores the importance of confirming that participants genuinely wish to receive their research outcomes, as theoretical interest may not necessarily convert into a desire to learn one’s risk of Alzheimer’s disease dementia when it is actually presented.

The study published on May 6 in JAMA Network Open.

“Overall, there is a trend toward providing research participants and patients with their test outcomes, even in instances where no actions can be taken based on those outcomes,” stated senior author Jessica Mozersky, PhD, an assistant professor of medicine at the Bioethics Research Center and an investigator at the Charles F. and Joanne Knight Alzheimer Disease Research Center, both affiliated with WashU Medicine. “However, our research indicates that in delicate scenarios — such as estimating the likelihood of developing a debilitating and fatal illness — individuals should have the choice to remain uninformed.”

In recent years, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine have suggested that research study designs should generally include the option for participants to receive test outcomes, even when such results cannot prompt any action. Similarly, a committee comprised of study participants, their caregivers, and members of dementia advocacy groups recently proposed a bill of rights for Alzheimer’s disease research participants advocating for access to such outcomes.

Simultaneously, ethical issues still persist due to the risk of inducing anxiety and other harm to participants who discover they are at high risk for developing a debilitating and irreversible dementia. Unlike preventive options available for individuals learning about a high genetic predisposition to certain cancers, for instance, there are presently no sanctioned preventive therapies or medical interventions that can delay the onset of Alzheimer’s disease dementia.

To gain a clearer understanding of who refrains from receiving Alzheimer’s disease dementia risk results and the rationale behind it, Mozersky and her team examined extensive research at WashU Medicine’s Knight Alzheimer Disease Research Center. Since 1979, the Memory & Aging Project has established a framework to study brain function in participants as they age. Over the years, the project has evolved and branched into various long-standing studies concerning the development and progress of Alzheimer’s disease, especially regarding the creation of biomarker tests to assess risk.

For the current examination, Mozersky’s team concentrated on cognitively normal volunteers who underwent a series of evaluations, including genetic assessments, blood collection, and brain imaging, from which researchers could predict their likelihood of developing Alzheimer’s disease dementia over the subsequent five years. Participants initially joined the long-term study with the understanding that they would not have the option to obtain their personal risk results. Nevertheless, Mozersky noted that many have expressed a hypothetical interest in receiving their results over the years. The study, co-led with Sarah M. Hartz, MD, PhD, a professor of psychiatry at WashU Medicine, provided results to a subset of participants in the Memory & Aging project — 274 individuals — to evaluate the psychological impact of learning their risk and the considerations they weigh in making that choice.

Before making a decision, participants received an informational guide detailing how risk is assessed and featuring examples of the advantages and disadvantages of obtaining their results. For instance, one advantage could be discovering that their risk is lower than anticipated. Furthermore, if biomarker testing indicates a participant is at high risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease dementia in the next five years, they might become eligible for clinical trials of experimental prevention methods. Conversely, learning about a high risk may induce anxiety or complicate the acquisition of certain types of insurance.

When the results were hypothetical, 81% of respondents from the broader long-term study indicated they would choose to know. In contrast, when actual results were offered to the 274 participants in the Memory & Aging Project, only 60% opted to receive them. Participants with a family history of Alzheimer’s disease and those who identified as African American were more inclined to refuse the results than others.

In a recent investigation, researchers at WashU Medicine found a substantial discrepancy between the percentage of participants expressing a desire to learn their risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease dementia if these estimates were accessible and the percentage who followed through with learning those results when offered the genuine option. (Image: Sara Moser/WashU Medicine)

A sample of participants who chose not to learn their results were interviewed afterward, with the most common reasons provided being that knowledge would be a burden to themselves or their family, their own negative experiences and perceptions of Alzheimer’s disease dementia, feeling confident about their current memory, believing they are already prepared for the illness, and recognizing the ongoing uncertainty in disease risk predictions.

“The absence of preventive treatments is also a significant reason for declining to receive biomarker test results among individuals without Alzheimer’s disease dementia symptoms,” Mozersky stated. “When we conducted interviews with some participants to delve deeper into their choice not to know, many suggested that the emergence of a new effective treatment might alter their decision if it became available.”

Because these outcomes are only accessible through research studies, they do not become part of the participant’s medical records maintained by the investigators. However, such results could eventually be recorded in a patient’s medical file if a participant chooses to share them with their physician.

“We intend to continue our exploration into the intricacies of these issues, especially as the return of results to research participants becomes increasingly common, even when those results cannot yet lead to actionable steps,” Mozersky remarked.

Goswami S, Hartz SM, Oliver A, Jackson S, Oluwatomisin O, Evans A, Linnenbringer E, Moulder K, Morris J, Mozersky J. Research participant interest in learning results of biomarker tests for Alzheimer disease. JAMA Network Open. May 6, 2025.

“““html

This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), grant identifiers R01 AG065234, P30AG066444, P01AG003991, P01AG026276, and UL1TR002345.

Washington University possesses a financial interest in C2N diagnostics, which produces the Precivity AD plasma Alzheimer’s Disease biomarker examination, one of the assessments available to study participants. No individual researcher affiliated with this study holds a personal financial interest in C2N diagnostics.

plasma Alzheimer’s Disease biomarker examination, one of the assessments available to study participants. No individual researcher affiliated with this study holds a personal financial interest in C2N diagnostics.

About Washington University School of Medicine

WashU Medicine is an international frontrunner in academic medicine, encompassing biomedical research, patient services, and educational initiatives with 2,900 faculty members. Its National Institutes of Health (NIH) research funding portfolio ranks second among medical schools in the U.S. and has increased by 56% over the past seven years. Alongside institutional funding, WashU Medicine invests over $1 billion each year into fundamental and clinical research advancement and training. Its clinical practice consistently ranks among the top five nationwide, with more than 1,900 physician faculty serving at 130 sites and also providing medical staff for Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals under BJC HealthCare. WashU Medicine boasts a rich history in MD/PhD education, having recently allocated $100 million towards scholarships and curriculum improvements for its medical trainees, and hosts excellent training programs across all medical subspecialties along with physical therapy, occupational therapy, and audiology and communication sciences.

First published on the WashU Medicine website

The article Most people say they want to know their risk for Alzheimer’s dementia, fewer follow through was first seen on The Source.

“`