Photo by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Arts & Culture

More than simply blue

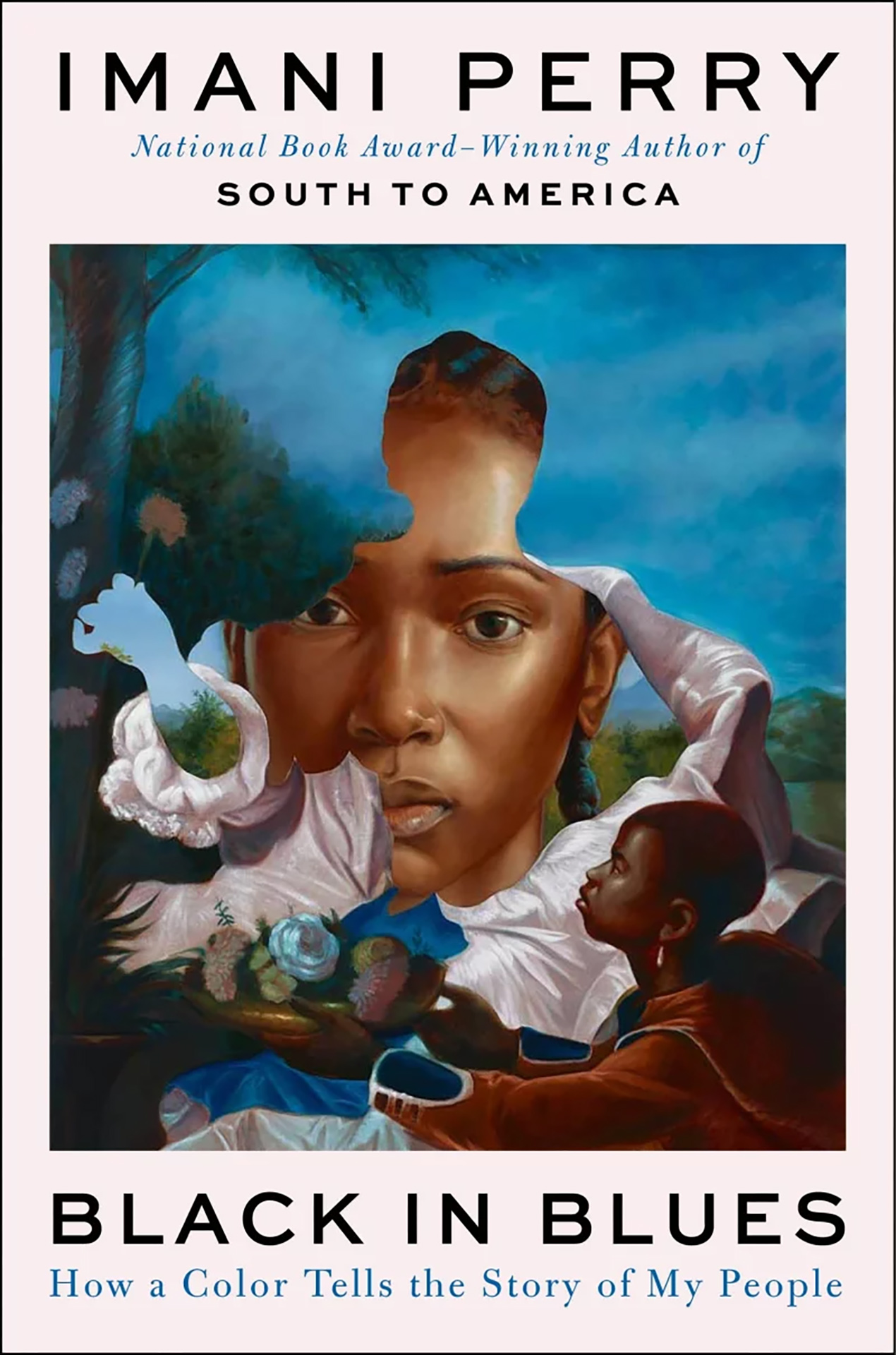

Imani Perry’s poetic new publication intertwines memoir and history to evaluate the essential role of a color in Black America

Imani Perry frequently spent nights in her grandmother’s room during her childhood. The walls were a muted gray, with a tile missing from the ceiling, which had been lowered to conserve heat. Through that void, she was able to glimpse the room’s original hue, a vibrant blue “like the sky in August.”

In her recent publication, “Black in Blues,” the National Book Award-recipient reimagines the void as a “portal” through which to examine the importance of the rich color within Black history and culture. Perry blends personal narrative and historical context to explore variations of blue originating from Africa, traveling across the Atlantic, and arriving in the Americas through the perspectives of the Black diaspora.

The Gazette conversed with Perry, the Henry A. Morss Jr. and Elisabeth W. Morss Professor of Studies of Women, Gender, and Sexuality as well as of African and African American Studies, and Carol K. Pforzheimer Professor at the Harvard Radcliffe Institute, regarding her new book, her first since her 2022 bestseller “South to America.” This dialogue has been refined for clarity and length.

What was the creative process like for “Black in Blues”?

I drew significant inspiration from the African American artist Romare Bearden. There’s an article in which music reviewer and novelist Albert Murray discusses Bearden’s methodology for creating collages. When you observe the artwork, you see imagery, yet each element he’s cut out stands as an individual piece of art.

For Bearden, organizing all these elements to create a cohesive picture was akin to how the beauty of [classical jazz] manifested in his visual creations. For me, this compositional aspect influences how visual art and music intertwine in my writing.

The book functions as both a personal narrative and an exploration of Black history and culture. Why was it essential for you to integrate your personal experiences and connections to the color blue into this work?

A great deal of what I was intuitively navigating—emotionally, intellectually, and spiritually—was grounded in my experiences and interactions with blue. So, that aspect was significant.

The connection I formed with blue stemming from my nights spent in my grandmother’s bedroom was vital. In some respects, I regard this missing tile in her ceiling as the portal that helps me to contemplate—not solely why it evoked certain feelings but also how to narrate a story surrounding that.

Your book highlights that blue is often explored by Black authors, scholars, and artists. Why do you believe this occurs?

On one level, it’s due to the universality of blue. Blue is held in high regard globally, with references to the color present in every cultural tradition.

There’s a specific essence that emerges in Black existence tied to the legacy of the transatlantic slave trade and our relationship to ports. These locations served as havens for nurture, worship, and reflection, while also being sites of tremendous suffering. This is why I assert that Black existence is akin to an epic of water—one that embodies both disaster and places where individuals continually seek spiritual connections.

I endeavor to clarify at the start of the book the notion that Black individuals are relatively new in the context of human history. People were more than merely this label—this concept arose out of empire and its catastrophes, yet humans create meaning from that experience.

That reality also pertains to the color blue. I believe this is why the genre became known as blues music. Blue embodies a duality: it is both sorrowful and joyous. It represents water as terror, yet also as potential.

“Blue embodies a duality: it is both sorrowful and joyous. It represents water as terror, yet also as potential.”

Early in “Black in Blues,” you write: “Black was a hard-earned love. But through it all, the blue blues — the certainty of the brilliant sky, deep water, and melancholy — have never deserted us … the blue in Black is nothing less than truth before trope. Everybody cherishes blue. It is quintessentially human. But not everyone cherishes Black — many have scorned it — and that is inhumane.” Can you elaborate on that potent statement?

At its essence, I want to highlight that there exists this color that captivates individuals because it represents a universal human experience. We perceive the waters, we behold the sky, and it exerts an influence upon us.

Conversely, there exists a classification of human beings aimed at degradation and insult. Yet, driven by our humanity, we craft something meaningful—even from that state—and we create culture and art. These elements simultaneously affirm the depth of the humanity of Black individuals while also engaging with this universally alluring color.

You later reflect on the resurgence of blues and the renaissance of creativity among Black women during the 1970s and 1980s. Why do you think this period was particularly significant for the color, sound, and artistry of blue?

In a way, the mainstream Civil Rights Movement served as an olive branch. It expressed a demand for rights but also extended an olive branch to the broader society from Black Americans, which was met with some legal advancements, yet frequently accompanied by hostility, whether through white flight or backlash against civil rights. Following this, there was a moment of introspection within Black communities, leading to a remarkable surge of artistic expression.

For Black women, this shift is especially critical, as it coincided with the women’s movement, the onset of the gay rights movement, and the Black Power movement. All these movements involved individuals from the margins finding their voice and space.

This combination of freedom’s power led to a magnificent surge of creative output, alongside unprecedented access to mainstream publishing houses. For me, that creative work was being produced at a time when I was maturing. I was born in 1972, and all the artistic endeavors of the ’70s were surrounding me—it’s an inheritance that I hold dear.

What do you hope readers gain from this newest endeavor?

I perceive my books as artifacts, and I hope that readers find them engaging and enjoyable, or at the very least, thought-provoking. However, above all, I view them as offerings—companion pieces to life and other works. I aspire for my readers to encounter a passage and then venture into the world, allowing that experience to resonate in how they perceive blue, thus generating new ideas or providing nourishment, healing, or inspiration.

With all my books—and my classroom endeavors—I consistently find myself both rooted in tradition and engaged in a dialogue. I continuously aim to highlight threads of connection with others—past, present, and future. I intend to extend an invitation to those who read the book, encouraging a conversation with me.