Investigations that traverse conventional boundaries of academic fields, as well as the divisions between academia, industry, and government, are becoming increasingly common and have sometimes led to the emergence of significant new fields. However, Munther Dahleh, a faculty member in electrical engineering and computer science at MIT, asserts that such multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary efforts frequently encounter various limitations and challenges when compared to more traditional, discipline-centric research.

He notes that the pressing dilemmas of the contemporary world — such as climate change, the loss of biodiversity, regulating artificial intelligence systems, and managing pandemics — necessitate a fusion of expertise from diverse domains, including engineering, policy-making, economics, and data analytics. This understanding inspired him, a decade ago, to establish MIT’s innovative Institute for Data, Systems and Society (IDSS), which seeks to promote a more cohesive and enduring set of collaborations than the typical temporary and ad hoc partnerships associated with such work.

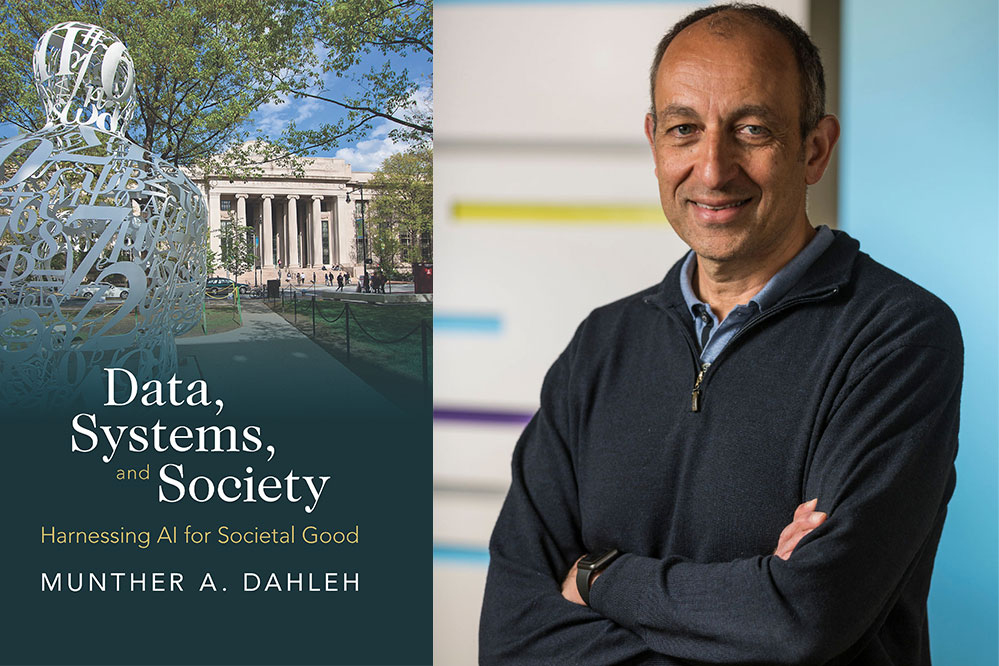

Dahleh has since authored a book that elucidates the process of evaluating the existing disciplinary divides at MIT and envisioning a framework designed to dismantle some of those obstacles in a sustainable and impactful manner, ultimately leading to the development of this new institute. The book, “Data, Systems, and Society: Harnessing AI for Societal Good,” was released this March by Cambridge University Press.

The publication, Dahleh mentions, represents his effort “to articulate our thought process that culminated in the vision for the institute. What was the foundational vision behind it?” He indicates that the book targets varied audiences, but specifically, “I’m aiming at students who are engaging in research to tackle societal challenges using AI and data science. How should they conceptualize these issues?”

A central idea that has informed the institute’s framework is what he refers to as “the triangle.” This concept encompasses the interplay among three elements: physical systems, individuals interacting with those systems, and regulations and policies governing those systems. Each element influences and is influenced by the others, he clarifies. “You observe a complex interaction among these three elements, and then there is data pertaining to all these aspects. Data acts like a circle that resides at the center of this triangle, connecting all the components,” he explains.

When addressing any large, intricate issue, he advocates for thinking in terms of this triangle. “If you’re dealing with a societal challenge, it is crucial to comprehend the effect of your solution on society, on the individuals, and the significance of individuals in the success of your system,” he states. Often, he observes, “solutions and technologies have marginalized certain demographics and overlooked them. Thus, the key message is to always consider the interaction among these components when devising solutions.”

He cites the Covid-19 pandemic as a notable example. It served as an ideal case study for a significant societal issue and illustrates the three sides of the triangle: the biology, which was initially poorly understood and subjected to intense research; the contagion effect related to social behaviors and interpersonal interactions; and the decision-making by political leaders and institutions regarding school closures, business restrictions, and mask mandates, among others. “The intricate challenge we faced stemmed from the real-time interaction of all these components, during a period when not all data was accessible,” he notes.

Making decisions, such as closing schools or businesses to manage the disease’s spread, had immediate repercussions on economics, social well-being, health, and education, “so we had to factor all these elements back into the equation,” he elaborates. “The triangle became particularly relevant for us during the pandemic.” Consequently, IDSS “served as a hub, partly due to the diverse facets of the issue that piqued our interest.”

Instances of such interactions are plentiful, he remarks. Social media and e-commerce platforms exemplify “systems designed for people, possessing a regulatory dimension, and they fit within the same narrative if one is trying to comprehend misinformation or the monitoring of such misinformation.”

The book outlines numerous examples of ethical dilemmas in AI, emphasizing the necessity of addressing them with great caution. He points to self-driving vehicles as an example, where programming choices in perilous situations might seem ethical but can result in adverse economic and humanitarian outcomes. For instance, while most Americans agree that a vehicle should prioritize the safety of its passengers over that of an innocent bystander, they would be reluctant to purchase such a car. This hesitance diminishes adoption rates and ultimately leads to higher casualties.

In the book, he clarifies the distinction, as he perceives it, between “transdisciplinary” efforts and standard cross-disciplinary or interdisciplinary research. “They each serve different functions and have achieved success in various ways,” he states. However, most such endeavors tend to be fleeting, which can restrict their societal significance. Even when individuals from distinct departments collaborate on projects, they often lack a framework of common journals, conferences, shared spaces and infrastructure, and a sense of belonging. Establishing an academic entity like IDSS that explicitly bridges these divides in a consistent and enduring manner was an attempt to remedy that gap. “It was fundamentally about fostering a culture where individuals could contemplate all these elements simultaneously.”

He quickly adds that these interactions were already occurring at MIT, “but we lacked a singular venue where all the students could engage with all of these principles concurrently.” For example, in the IDSS doctoral program, there are 12 required core courses — with half focused on statistics, optimization theory, and computation, and the other half on social sciences and humanities.

Dahleh stepped back from leading IDSS two years ago to return to teaching and continue his research. However, as he reflected on the institute’s work and his role in its inception, he recognized that, unlike his own academic research, where every step is meticulously documented in published articles, “I haven’t left a record” to capture the creation of the institute and the rationale behind it. “Nobody knows our thought processes, how we arrived at our conclusions, or how we constructed it.” Now, with this book, they have that insight.

The book, he expresses, is “sort of guiding people in understanding how all of this came together, in retrospect. I hope readers will approach this with a historical perspective, grasping how something like this came to fruition, and I have endeavored to make it as comprehensible and straightforward as possible.”