“`html

Harvard archival photograph

Campus & Community

Future of a Marine veteran was enigmatic. Then he discovered archaeology.

Shane Rice attributes Gen Ed class — and professor’s collection of declassified intelligence photographs — for clarifying career direction

Part of the

Commencement 2025

series

A series of features and biographies highlighting Harvard University’s 374th Commencement.

The professor’s office was adorned with declassified U.S. intelligence images.

“I entered, and the first thing that caught my eye were these enormous printouts of U2 and CORONA aerial visuals,” Shane Rice ’25 recounted. “I took a glance and thought — perhaps there’s something to explore.”

At 26, Rice, a U.S. Marine Corps veteran, required a new academic direction. Initially arriving from Warrenton, Virginia, he intended to pursue environmental engineering. Nevertheless, the discipline did not align well with his passions and capabilities. “Thus, I embarked on a search,” he recounted. “I lunched with various department heads, including those from integrative biology and environmental science public policy.”

The journey concluded in the office of Jason Ur, Stephen Phillips Professor of Archaeology and Ethnology, surrounded by a collection of aerial landscapes. This exhibition resonated with Rice, partially due to his military experience. As a mortarman, he often engaged with maps and satellite imagery throughout three deployments.

Rice was intrigued by Ur’s introductory course titled “Can We Understand Our Past?” The Cabot House resident, who acclimated to collegiate life thanks to the Warrior-Scholar Project and various veteran resources, later earned an award for his essay on the insights he gained from the Gen Ed course.

The curriculum, he noted, helped him merge a commitment to public service with a fascination for antiquities, data organization, and working in distant locations. “Shane articulated very effectively how studying archaeology assisted him in the transition to academia from military life,” Ur mentioned.

“Shane articulated very effectively how studying archaeology assisted him in the transition to academia from military life.”

Jason Ur

The Cold War-era visuals that enthralled Rice enable Ur to investigate sites in Syria, Turkey, and Iran. Since 2012, this technique has allowed Ur to explore the Kurdistan region of Northern Iraq for evidence of ancient atrocities. Rice became one of the rare undergraduates to participate in Ur’s fieldwork in the semi-autonomous area. He even applied Ur’s methods to uncover scars left much more recently in the region. Rice utilized declassified satellite reconnaissance to reveal hundreds of erased communities, all wiped out during Iraq’s crackdown on ethnic Kurds.

“In 1987, the Iraqi Army, under Saddam Hussein’s regime, eradicated the entire plain where we’re conducting our work of its rural Kurdish villages,” Ur stated. “The meticulous mapping Shane accomplished provides us with an excellent analogy for comprehending the distribution and density of rural settlements in the deeper historical context. Yet, it also serves as evidence of genocidal state actions.”

Making weekly visits to Ur during office hours became a new routine for Rice. It was there that he learned about the professor’s fieldwork near Erbil, the capital of the Kurdistan Region. Ur collaborates with researchers to analyze features from the Neo-Assyrian Empire (circa 900-600 B.C.)

“We are there to test the theory that the Assyrian monarchs engaged in mass deportations,” Ur elucidated, noting the rulers’ narratives are substantiated by their victims in the Hebrew Bible.

Also littering the region’s landscapes is proof of recent demographic assaults. Hussein was eventually held accountable for the deaths of tens of thousands of Kurds during the 1988 Anfal campaign. U.S. media reports have often centered on the government’s deployment of chemical weapons against Kurdish civilians, but have been less focused on the devastation, a year earlier, of rural farming communities.

“We don’t typically view the 1980s as particularly archaeological,” Ur remarked, who assisted Rice in selecting these villages for his thesis topic. “However, this represents the same tragic narrative echoed 3,000 years later by the Assyrians. And it truly required some dedicated inquiry.”

Rice was invited to join Ur on the Erbil plain just before his junior year. “I select my team very deliberately, as we essentially act as an extension of American diplomacy during our time there,” Ur noted. “Shane impressed me early on with his remarkable responsibility and discipline, which I attribute to his military background.”

The archaeology concentrator had contemplated specializing in nomadic pastoralists. Rice, who also completed a language citation in Russian, arrived in Erbil after spending weeks with reindeer herders in northern Mongolia. However, Ur’s work in the Kurdistan Region seemed far more pressing. “They’re racing against the clock with this project,” Rice explained. “They’re racing against urban expansion and sprawling development to document these sites.”

Upon returning to Cambridge, Rice promptly embarked on developing his own research initiative. Central to his approach was Ur’s graduate-level course on the archaeological applications of Geographical Information Systems. That semester, Rice began seeking government databases for declassified intelligence photographs that met his requirements in resolution, timescale, and coverage of the 3,000-square-kilometer survey area.

This led him to unearth a collection of high-resolution landscape images, declassified in 2013, that were obtained in June 1980 by the KH-9 Hexagon U.S. photo-reconnaissance satellite. “In an ideal scenario, you would contrast images taken immediately before and right after the event,” Rice noted. “However, 1980 was fairly close to the timeframe we were examining.”

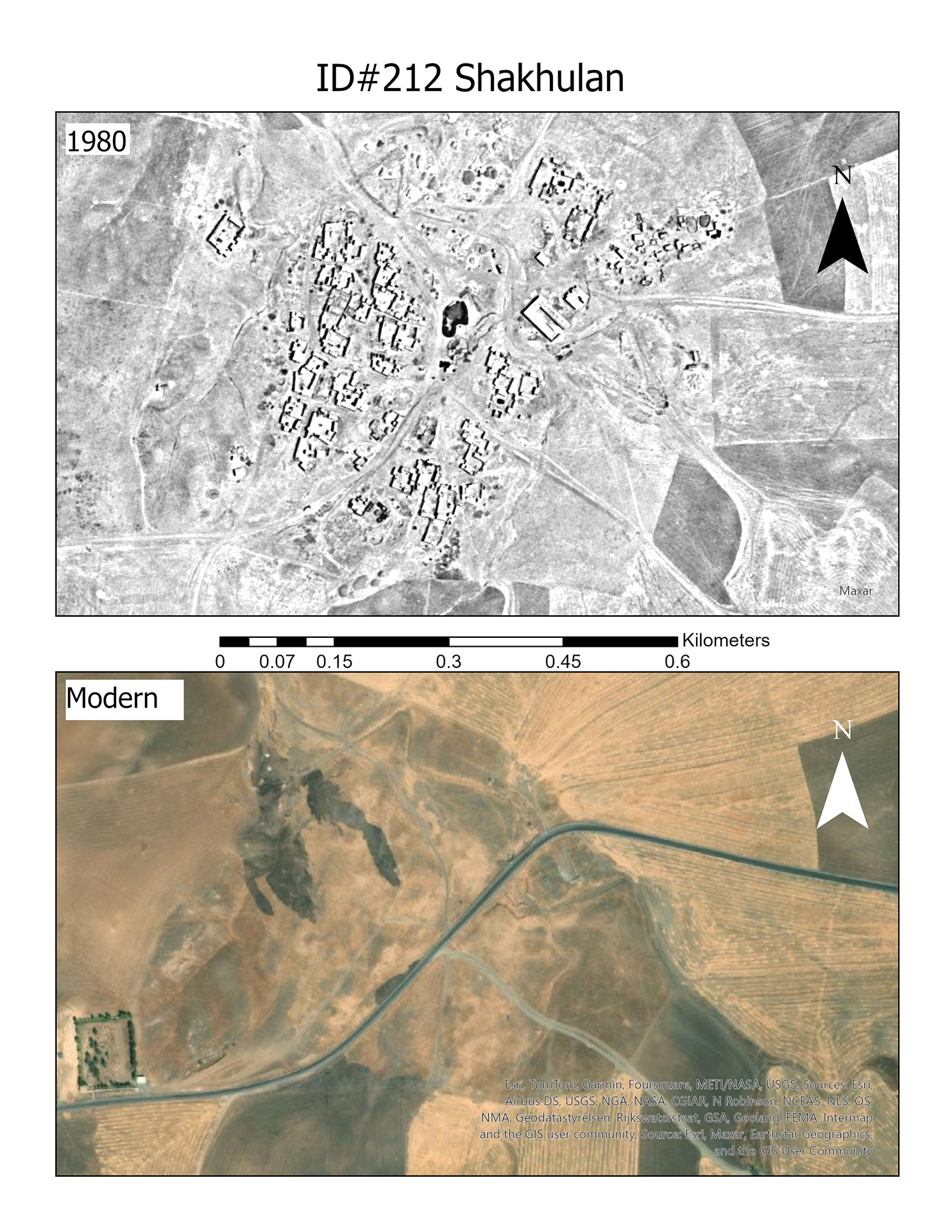

By aligning these satellite captures with contemporary commercial imagery, Rice was able to document hundreds of obliterated settlements. The community of Shakhulan, he discovered, had been razed, showing up in recent images as little more than cultivated land. In the places of other sites stood new constructions or ruins.

Rice compared images from 1980 and 2013 to document obliterated settlements in the Kurdish Region of Iraq.

Images courtesy of Shane Rice

“At times, there is literally the outline of the four walls that once constituted a building,” Rice remarked.

The 1980 images also unveiled a tightly organized refugee complex, or mujamma’a, that corresponded with one chronicled in a 1993 Human Rights Watch document. By that point, the undergraduate had grasped the general contours of history from his Kurdish collaborators and friends. The Anfal campaign was preceded by years of the Iraqi military forcibly relocating Kurds to tent encampments similar to the one he identified 25 kilometers south of Erbil.

“These locations have existed solely in oral tradition and memory,” Rice stated, who will commence his studies at Cornell Law School in the fall. “And here we possess primary-source evidence of one of these sites that thousands of individuals and families were transitioned through. To me, that underscores the true significance of undertaking this project.”

“`