Arts & Culture

Allowing the portraits to express themselves

Artist Robert Shetterly ’69 and Brenda Tindal, head campus curator.

Photos by Niles Singer/Harvard Staff Photographer

New exhibition amplifies marginalized voices as it investigates hope, transformation, and our perceptions of others

In 2002, two Harvard associates, artist Robert Shetterly ’71 and the late Harvard Medical School Professor of Neurology S. Allen Counter, initiated portrait projects inspired by a quest for change. Shetterly, disheartened by the U.S. government’s choice to engage in war in Iraq, had turned to depicting individuals who motivated him as a form of dissent and comfort. Concurrently, Counter, the founding director of the Harvard Foundation for Intercultural and Race Relations, aimed to tackle representation issues by diversifying the portraits displayed throughout Harvard’s campus.

This resulted in Shetterly’s “Americans Who Tell the Truth” series and the Harvard Foundation Portraiture Project, both of which utilize portrait art as a means of narrative to amplify overlooked narratives.

“Each individual I portray possesses a distinct kind of bravery that matches a specific moment,” Shetterly shared with chief campus curator Brenda Tindal in front of an audience at Cabot House. “They often risk being excluded by society or embroiled in legal complications, which places them in an adversarial relationship with significant factions of this country. I am profoundly attracted to that. It’s this courage that leads us to social justice.”

“Each individual I portray possesses a distinct kind of bravery that matches a specific moment.”

Robert Shetterly

Last week, the Office for the Arts, the Harvard Foundation, and the Harvard College Women’s Center presented an exhibition at Cabot that showcased portraits of Harvard affiliates from both projects. Titled “Seeing Each Other: A Dialogue Between the Harvard Foundation Portraiture Project and Americans Who Tell the Truth,” it featured paintings from Shetterly and the Portraiture Project’s Stephen Coit ’71.

In celebration of Women’s Week, the portraits highlighted female change-makers, such as former U.S. Treasurer Rosa Rios ’87, musicologist Eileen Southern, civil rights advocate Pauli Murray, ethnomusicologist Rulan Pian, youth development supporter Regina Jackson, and former Maine State Sen. Chloe Maxmin ’15. Portraits of Counter and W.E.B. Du Bois, the first Black Ph.D. graduate from Harvard, were also featured.

“History reminds us that the struggle for gender equity has frequently been bolstered by allies who have leveraged their platforms to confront injustice and elevate the voices of those most marginalized,” remarked Habiba Braimah, senior director of the foundation, initiating the dialogue between Tindal and Shetterly. “By displaying their portraits alongside the remarkable women we celebrate tonight, we emphasize that significant progress is attained through both advocacy and unity, reaffirming the notion that the quest for gender equity has perpetually been, and must remain, a collective responsibility.”

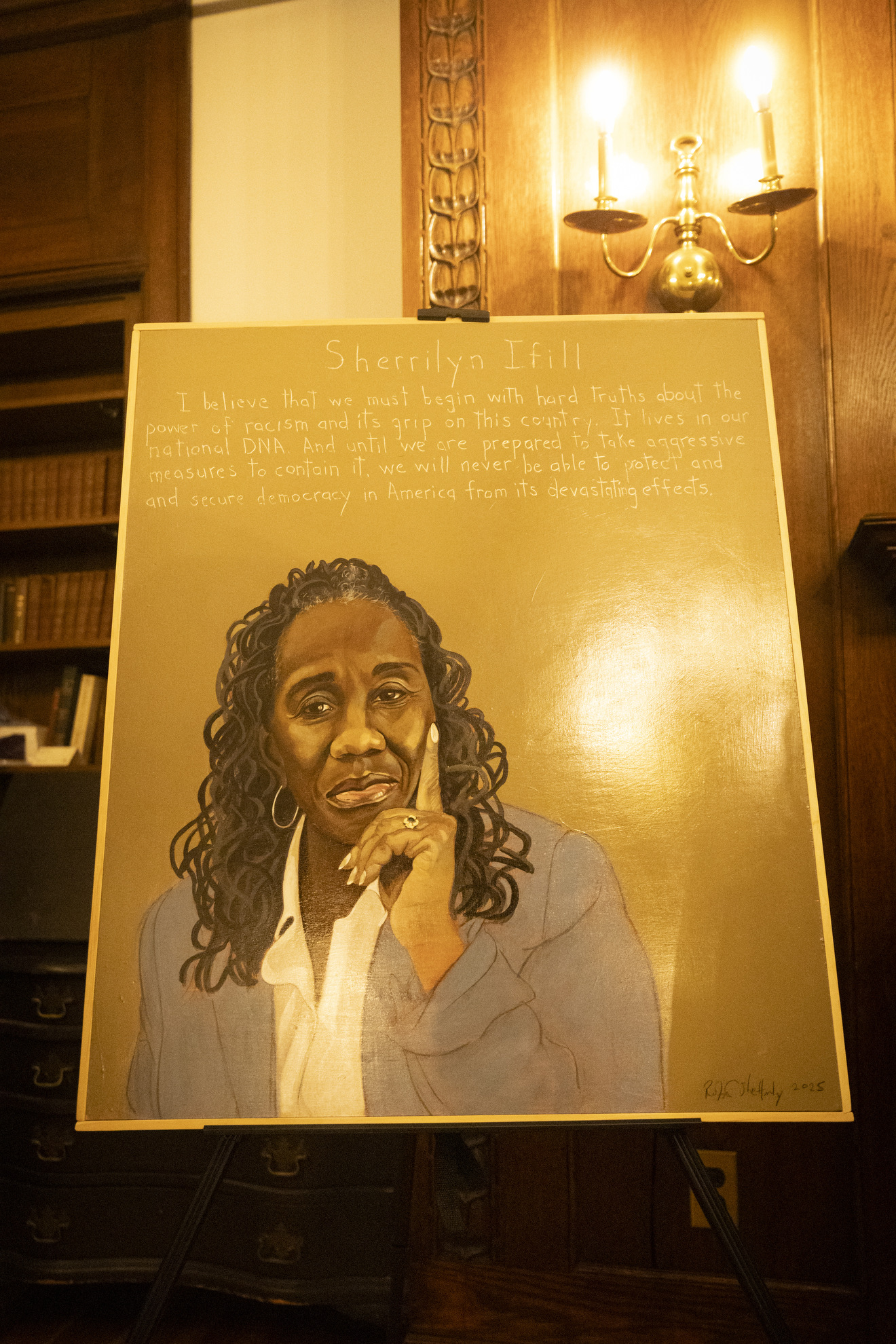

During the exhibition opening, Shetterly also unveiled a new portrait of civil rights attorney Sherrilyn Ifill, the former president of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, who was the Steven and Maureen Klinsky Visiting Professor of Practice for Leadership and Progress at Harvard Law School from 2023 to 2024. In the artwork, Ifill, clad in a blue blazer, stares outward with a contemplative demeanor, her chin resting on one hand.

Having attended Ifill’s 2024 Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Commemorative Lecture at Harvard, Adaolisa Agbakwu ’28 recalled being touched by the attorney’s analogy of the Civil Rights Movement as a cycle of planting and reaping — preparing the groundwork for future generations to enjoy the rewards.

“The warmth of the portrait, alongside its cool undertones, resonated with me as a reflection of her inner solace mingled with the intense passion and fervor she embodies for her work and dedication to the cause that she demonstrates in all her endeavors,” Agbakwu expressed.

In his discourse with Tindal, Shetterly mentioned that what commenced as a goal to produce 50 portraits for his series has since expanded into a collection exceeding 200. Shetterly enrolled in his first art class at Harvard — a drawing class at the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts.

“What I discovered was that when I had to examine something — whether it be my own hand, an apple, a pencil, an old shoe, or a glove — in order to sketch it, I had to truly see it for the first time,” Shetterly reflected. “That transformed my life.”

Shetterly employs wood panels with brushes, palette knives, and his fingers, and carves a quote from his subject into the wood above their depiction with a dental pick. He explained that the incorporation of quotes was partly inspired by the fact that most gallery visitors spend only seven seconds observing a painting, motivating him to encourage them to slow down and engage.

“Having the words engraved into the surface adds a different weight compared to if they had been painted on,” Shetterly noted. “Once integrated into the artwork, they appear somewhat stronger, more organic, as if they genuinely originate from the individual in the portrait.”

Coit, who has contributed over two dozen portraits to the Harvard Foundation Portraiture Project, conveyed to the audience that he views his role as showcasing what his subjects desire to express about themselves.

“When I painted someone, I would inquire, ‘What do you wish to convey in your portrait?’” Coit shared. “We would think about the backdrop, their attire, the expressions on their faces, and they crafted it alongside me. I always perceived my task as creating a semblance of immortality, so it seemed as though they were present with you, delivering that message.”