A research paper co-written by economist David Deming explores the transformation induced by technology in the U.S. employment landscape over a century.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Employment & Economy

Is AI already disrupting the labor market?

4 patterns indicate significant transformation, according to researchers who analyzed a century of technological interruptions

A recent publication from Harvard economists David Deming and Lawrence H. Summers presents initial evidence indicating that artificial intelligence is disrupting the workforce.

The research analyzes over a century of “occupational turnover” — or each profession’s portion in the U.S. job market — for a historical perspective on technological disturbances. It revealed a period of stability from 1990 to 2017, which contrasts with common narratives about robots taking American jobs. Nevertheless, the study also uncovered a recent alteration, with the authors identifying a number of trends influenced, at least in part, by AI.

“We initially presumed the paper would conclude something like, ‘See, we told you so. Things aren’t changing significantly,’” remarked Deming, the Isabelle and Scott Black Professor of Political Economy at Harvard Kennedy School and Faculty Dean of Kirkland House. “Yet as we delved into the data, it turned out the narrative was slightly more nuanced — and more fascinating in some respects — than we had anticipated.”

For years, Deming and Summers discussed the idea of assessing occupational turnover in the U.S. job market over the years. “It would provide a systematic method to evaluate how various technologies have impacted work,” explained Deming, who is the lead author of the paper.

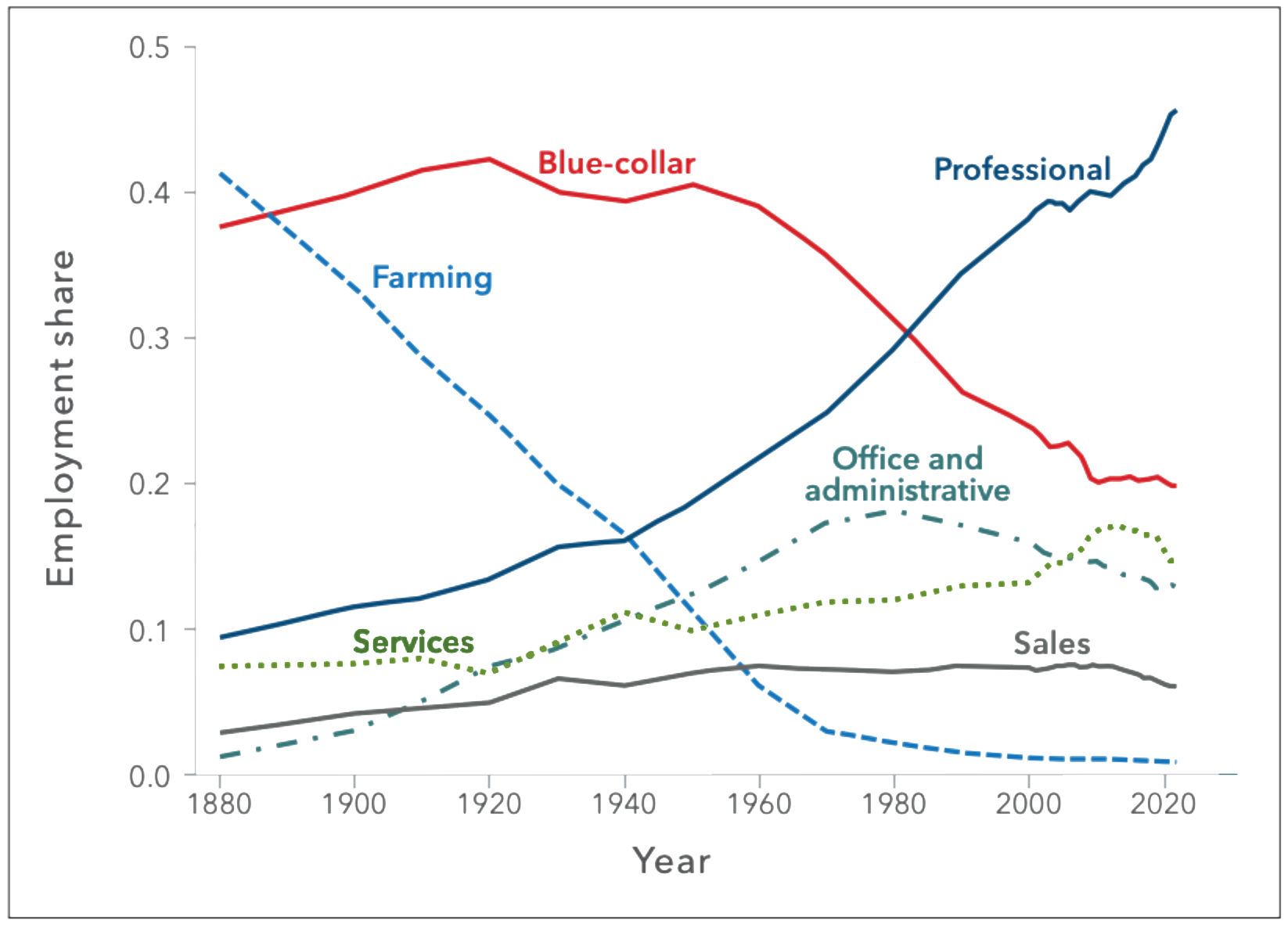

Job market fluctuations throughout the past century

Industry employment share, 1880-2024.

Source: “Technical Disruption in the Labor Market”

Last year, the economists employed this metric with assistance from Kennedy School predoctoral fellow Christopher Ong ’23, who is the third author of the paper. Their results, based on 124 years of U.S. Census data, were first published in a volume released last fall by the Aspen Economic Strategy Group. Summers, a member of the OpenAI board, shared further forecasts during a live discussion at the Aspen Ideas Festival.

Summers expressed initial astonishment at the degree of fluctuations detected in the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s that resulted from the emergence of what are known as “breakthrough general-purpose technologies.” “However, upon reflection, it wasn’t surprising,” stated the Charles W. Eliot University Professor and Frank and Denie Weil Director of the Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Business and Government at Harvard Kennedy School. “In the past, only a small group of individuals used keyboards. Now, virtually everyone uses keyboards, and there are fewer individuals whose entire job involves keyboard usage. This turned out to be a substantial structural shift that the economy adjusted to.”

The 2000s and 2010s were marked by what Deming referred to as “automation apprehension.” He cited an influential study from 2013 claiming that 47 percent of U.S. jobs were at imminent risk of being replaced by technology. However, the occupational turnover metric revealed that the rate of disruption began to decelerate by 1990 as the job market entered a phase of low turnover.

Then, an additional surprise emerged in the data. “From 2019 onwards,” Deming observed, “it appears that changes have been occurring quite significantly.”

“Everyone ought to be contemplating AI, irrespective of their profession.”

Lawrence H. Summers, study co-author

Is AI a transformative technology akin to keyboards, electricity, and computer-driven manufacturing? The findings of the co-authors led them to this conclusion. As evidence, they highlight four emerging patterns in the U.S. job market.

The first relates to the cessation of what economists have referred to as job polarization — a barbell-like distribution, with the labor market expanding at both the high and low ends of wage scales.

Recent discoveries revealed a one-sided trend favoring well-compensated workers with advanced training and skills. “The concern during the 2000s was about the downward trend,” noted Deming. “That indicated the growth of low-wage jobs, while the middle- and high-wage positions were stagnant. It was not until the late 2010s that we observed an upward trend, predominantly in high-wage occupations that are expanding.”

A prevailing trend, associated with the initial one, reveals a recent surge in positions within science, technology, engineering, and mathematics following a surprising decline in the 2010s. The proportion of roles in STEM — comprising software engineers and data analysts — escalated from 6.5 percent in 2010 to almost 10 percent by 2024. “That may not appear significant,” Deming remarked. “However, it signifies an almost 50 percent increase.”

Examining information sourced from the Census along with the Federal Reserve Bank illustrated that companies are not only employing more technical specialists, but they have also begun to make unprecedented investments in cutting-edge technologies like AI. “There’s really no need for speculation regarding AI’s influence on the workforce,” Deming pointed out regarding these insights. “Investment in AI is already transforming the job landscape.”

The research also detected stagnant or decreasing employment specifically within low-wage service positions. Mapping the occupational turnover in this sector, which experienced considerable expansion from 1980 to the early 2000s, indicated a sharp decline as of 2019. AI is merely one plausible reason, Deming stressed. Other factors may include increased wages, a more competitive job market, and temporary disturbances related to COVID-19.

“However, it seems that many of these positions will not be reappearing,” Deming continued. “The ones that have resurfaced are in food service, personal services such as manicurists and hairstylists, medical assistants, and a few cleaning roles.”

The research’s fourth observation indicates a particularly significant downturn, driven by technology, in retail sales positions. From 2013 to 2023, the proportion of retail sales jobs diminished from 7.5 to 5.7 percent of the labor market, equating to a 25 percent decrease.

The co-authors highlight that the e-commerce industry was an early user of predictive AI and has more than doubled its share of total retail sales since 2015.

“I perceive the pandemic as a catalyst, a situation that was going to unfold regardless,” Deming stated. “When individuals were informed that it was hazardous, potentially even fatal, to shop in person — they had to resort to online shopping — they found it was actually quite manageable and developed new habits.”

“Everyone should be considering AI, irrespective of their profession,” Summers emphasized. “Because AI can be immensely empowering. However, it also indicates that certain types of tasks will no longer be performed by humans.”

The paper presents a valuable insight for professionals in fields such as finance, management, and journalism. Automation has indeed displaced American jobs over the past century. In a Substack post, Deming referred to the early 20th-century case of telephone operators. Yet, AI’s effects are more likely to facilitate short-term increases in productivity while posing long-term risks of replacement by workers more proficient with the technology.

“As companies begin to feel the pressure — when we encounter the next recession or something similar — they will start seeking more from knowledge workers,” Deming articulated. “They will not expect that memo in two days, because they understand this technology exists. They will require it within two hours.”