Although located in the vibrant center of St. Louis, Washington University is deeply connected to its surrounding environment. Featuring a varied assortment of 6,500 trees across its Danforth Campus, WashU has held the title of “Tree Campus USA” since 2010 and achieved the distinguished level-three Arboretum designation last year. Furthermore, WashU’s landscape functions as an essential green corridor and habitat for avian species and urban creatures, largely due to its closeness to Forest Park. Notable sightings on campus include a pair of “paired” red-tailed hawks monitored through the Forest Park Living Lab and WashU’s Living Earth Collaborative.

“The campus provides green areas that benefit everyone: not only students and faculty but also the diverse wildlife that inhabit WashU,” remarks Jonathan Losos, the William H. Danforth Distinguished Professor, professor of biology, and director of the Living Earth Collaborative. He notes that in recent years, a variety of species such as red foxes, skunks, opossums, raccoons, shrews, and field mice have been observed on campus.

A significant part of what draws individuals to WashU’s Danforth Campus is the tranquil natural hideaways it offers visitors. Students frequently establish favored spots near the Elizabeth Gray Danforth Butterfly Garden in spring or lounge beneath the trees as soft yellow ginkgo leaves blanket the ground in autumn. Close to Olin Library, the Japanese flowering crabapple creates a cool canopy, making it the perfect reading (or napping) location during sweltering months.

Green areas and education go hand in hand. In fact, there is an increasing agreement that access to green spaces enhances learning by refreshing attention, promoting greater participation, and alleviating stress.

Yet it’s not exclusively students who reap the rewards from connecting with nature. WashU’s faculty also draw inspiration from it.

The process begins with tackling a challenge or identifying an issue and striving to think beyond conventional limits. Here, the focus lies on the word “outside.”

Regardless of their disciplines—be it business, engineering, art, or science—WashU faculty uncover new concepts and inventive solutions by looking toward the natural world.

Here are just a few instances.

Transforming the cultural narrative

Patricia Olynyk is an artist engaged with themes relating to science and technology, frequently collaborating with scientists, humanists, and technicians to investigate a broad spectrum of subjects, including those that pertain to mathematical patterns found in nature.

She also produces art that “makes you conscious of your own existence within the environment,” she states, referring to her Sensing Terrains and Dark Skies installations.

Olynyk, who serves as the Florence and Frank Bush Professor at the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts, often explores the intersection between mathematics and the “umwelt,” or our perceptual world.

In the case of Sensing Terrains—Olynyk’s extensive exhibition at the National Academy of Sciences, which featured silk prints of enlarged scanning electron micrographs (SEMs) of human and nonhuman specimens accompanied by ambient sounds from Japanese gardens aimed at “stimulating the senses”—the intention was to present “a distinct choreography of nature.”

The goal, she claims, is “to highlight that the state of being sensate is not solely human.” Olynyk strives to provoke thoughts about how perceptions interact with nature in numerous ways. “What does that signify concerning where we stand in this uncertain time?” she queries.

In Dark Skies, released in 2016, she drew “inspiration from the breathtaking cinematic experience of the sunset and my concern regarding our global loss of dark skies largely due to light pollution.” The artwork replicates sunset hues but features a blurred, irregular surface, with smudges of dark shades merging into reds and yellows. It aims to evoke the intersection of light with night, illustrating how artificial human light consumes it.

In another endeavor, Oculus, she presents a vast amoeba-like sculpture adorned with red eyes resembling gemstones, instilling a sense of surveillance as well as a skewed representation of what might be a genetically engineered fruit fly.

“I’m attempting to generate more intriguing inquiries about the intricate world we inhabit.”

Patricia Olynyk

Olynyk delineated grid patterns inspired by the mathematics of natural shapes, then distorted these forms, exaggerating some grid sections while minimizing others. There are no definitive conclusions about what viewers should derive from Olynyk’s creations. Her objective, instead, is to encourage questioning.

“I’m attempting to generate more intriguing inquiries about the intricate world we inhabit,” she expresses.

Moreover, she does not confine herself to a single medium, form of art, or scientific discipline. Her latest work, showcased at Bruno David Gallery in St. Louis last fall, was a collaboration with cinematographer Adam Hogan. The video, “Black Swan in Three Variations,” examines what individuals can learn from highly unlikely “black swan” occurrences, reflecting on financial downturns, the emergence of AI, and even the sinking of the Titanic.

Encouraging fresh viewpoints on significant events is another prominent theme in her work. She continually contemplates climate change and the necessity to transition the discussion from simply “awareness” toward envisioning new possibilities. “Until you conceptualize a new world, people will remain inactive,” she states. “We need to transition the cultural imagination toward narratives that explore where we’ll all be in 50 years.”

The humble mussel

Synthetic biology is transforming the way we “program” biological systems—allowing engineers to devise new proteins, manipulate metabolic pathways, and harness the biosynthesis capabilities of microbes. It resembles setting up a biological circuit board. When executed successfully, scientists could potentially utilize these biological “switches” to program microbes (such as fungi, yeast, bacteria, and algae) to create valuable materials, food, or fuel.

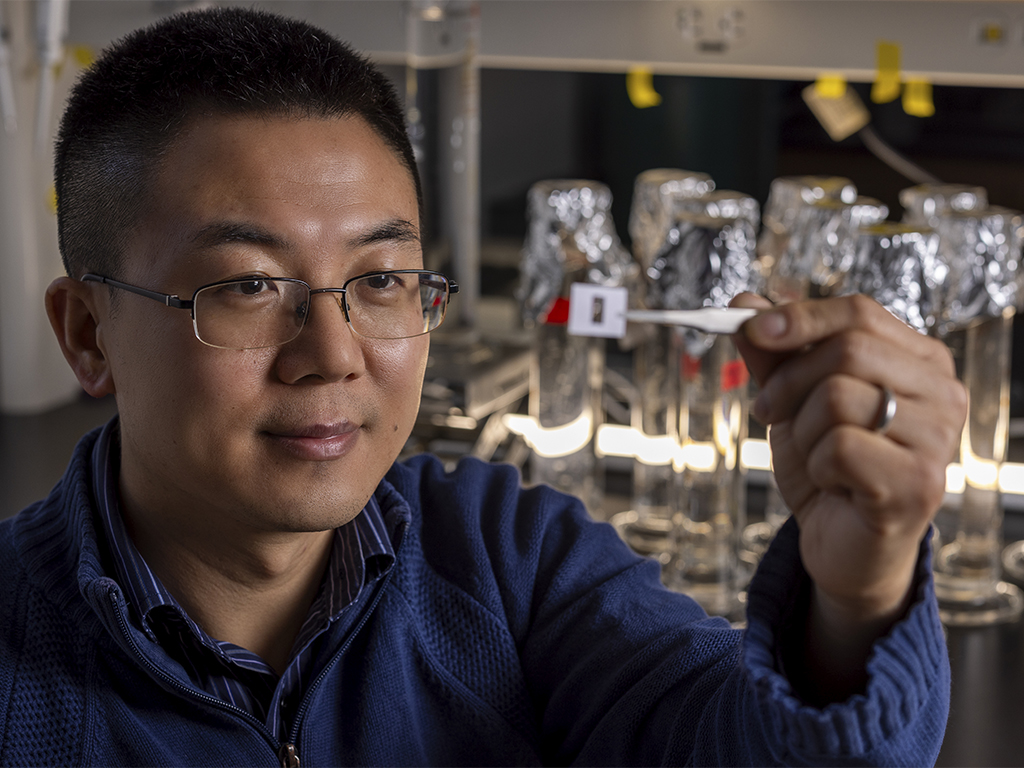

Picture the methods employed to brew beer—using tanks of yeast biochemically manipulated to ferment sugars into alcohol—applied to essentially everything. It may seem like a science-fiction fantasy, but it’s becoming increasingly feasible daily, thanks to the contributions of Fuzhong Zhang, the Francis F. Ahmann Professor within the Department of Energy, Environmental & Chemical Engineering at the McKelvey School of Engineering.

Zhang continually draws inspiration from nature, for in many instances, “nature” has already provided solutions to challenges.him. Consider, for example, the obstacle of mass-producing fiber substances to substitute petroleum-based nylon and polyesters. Spiders produce some of the most robust and durable fibers on the planet, which are also biodegradable; however, these solitary and predatory arachnids are not suitable for labor tasks.

Throughout the last ten years, Zhang has been “programming” bacteria to synthesize fibers that resemble genuine spider silk. However, to create fibers that are stronger than spider silk and yield significantly more, he and his team harnessed the properties of adhesive creatures: mussels. The proteins secreted by a mussel’s foot are extremely “adhesive,” making them an excellent molecular instrument for material innovation.

Mussels generate tiny threads at the base of their shells, functioning as their adhesive “feet.” “We utilize these sticky ‘feet’ to bond silk proteins together and, ultimately, enhance the strength of our microbe-generated fibers,” Zhang states. By combining the mussel-foot protein with spider-silk proteins, Zhang and his collaborators have managed to finally unravel the secret to high yield and robust threads, suitable for premium protective fabrics such as bulletproof vests.

Observing nature allows researchers to address multiple challenges simultaneously. Zhang’s team also employed the mussel-foot/spider-protein mixture to develop biocompatible adhesives for surgical applications. Conventional medical adhesives tend to be either inadequate for surgical repairs or could provoke allergic reactions, remarks Zhang. “However, our mussel-inspired protein adhesives are both strong and biocompatible, making them potentially ideal for various medical repair scenarios,” he elaborates. If clinical trials proceed successfully, this mussel-inspired glue could effectively close wounds in different organs, potentially saving time and even lives.

Zhang is dedicated to his research. Not only is he advancing synthetic biology, but he is also pioneering a future in which humanity can eventually replace the plastics harming the planet. As co-director of the Synthetic Biology Manufacturing of Advanced Materials Research Center (SMARC), he and his engineering peers at McKelvey are working on innovative classes of biologically synthesized, mechanically robust, and biodegradable materials that draw inspiration from nature to supplant traditional petroleum-based plastics.

The melodies of nature

The “Pines of Rome” is a renowned musical piece from the 1920s by the Italian composer Ottorino Respighi. The “Pini di Roma” possesses a sweeping sound, almost regal, invoking the majestic pines surrounding the city of Rome. When Christopher Stark chose to create a new rendition of this classical piece, he visited locations in Italy and discovered that much had altered over the past century. Unfortunately, the pines are perishing due to an invasive parasitic insect.

“Other Pines,” composed by Stark nearly a century later, replaces the regal sounds with ominous tones to evoke the disjointed experience of living in a world impacted by climate change.

Stark, associate professor of music composition in Arts & Sciences, has continuously contemplated nature and change from the onset of his career. “Coming from the West, it’s simply something I consider,” Stark explains, hailing from Montana. “Much of music shares the physical and mathematical qualities that resemble various natural phenomena.”

His latest work incorporates field recordings of fire, wind, and water. Released in 2021, Stark’s “Fire Ecologies” composition emerged from a trip to the West Coast during the wildfire season in 2020. He captured sounds of wind in both deciduous and coniferous forests to compare the auditory experiences; he recorded the crackling of fire, getting as close as possible.

While Stark’s work has centered on climate change, he also seeks nature for inspiration in a broader sense. He reflects on how to elicit emotions through music, and nature’s sounds can certainly achieve that in numerous ways. “Should I leave the audience feeling unsettled? Or inspire them with wonder and motivation to conserve nature?” he ponders, while examining the contrast.

“Should I leave the audience feeling unsettled? Or inspire them with wonder and awe and motivation to conserve nature?”

Christopher Stark

Composers acquire classical techniques to help them generate tension within their work, and Stark achieves similar impacts with his landscape recordings. For instance, in his “Language of Landscapes,” he utilized a recording from a lake—the sound of water gently lapping against the shore—and gradually removed elements from the digital audio file. This distortion renders the sound increasingly uneasy, portraying “the notion that this natural resource is diminishing,” he states.

“I am genuinely enthusiastic about seeking parallels like that between musical techniques and emotions, or sociopolitical commentary,” he expresses.

Many listeners of contemporary classical music perceive it as “challenging” or “unpleasant,” but Stark emphasizes that “the interpretation of noise can shift incredibly from distressing to soothing.” The sounds of fire, wind, and water are indeed intricate and “noisy,” yet equally capable of inducing calm.

“It’s enjoyable to replicate those sounds with instruments to evoke similar sounds coming from natural occurrences,” he remarks. “The contrast between what is synthetic and what is natural is profoundly intriguing.”

The chaotic wander

One takeaway from Hurricane Helene, which inundated North Carolina last fall, is that weather phenomena will become increasingly unpredictable and extreme as the planet continues to heat up due to climate change. This is precisely why Claire Masteller’s methodology in examining river systems revolves around “embracing the variability and chaos of the natural world,” she claims.

The greater humanity attempts to exert control over natural forces, the more unforeseen outcomes emerge downstream (quite literally in this case). Therefore, Masteller, an assistant professor of earth, environmental, and planetary sciences in Arts & Sciences, investigates the principles governing rivers: what keeps some narrow while others lose cohesion and flood.

Her personal voyage into “geomorphology” meanders similarly to a river. Growing up as a “Jersey Shore” girl on the barrier islands of lower New Jersey, she was a first-generation college student at the University of Pennsylvania, dabbling in various disciplines from fine arts to international relations until she discovered her passion for geosciences. She subsequently obtained a doctorate on the opposite coast, at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and then traveled abroad for a postdoctoral position.

possibilities in Germany. Ultimately, Masteller found herself in St. Louis, an exceptional river area, characterized by the merging of two major North American rivers: the Mississippi and Missouri.

She could not have chosen a more ideal location to dive into the “fundamental details” of river dynamics, meticulously examining how a single grain of sediment shifts. This is possible due to the “mini river” in her laboratory, an elongated plexiglass channel she employs to conduct experiments on erosion in gravel riverbeds. Her research is guided by empirical data and observations, incorporating satellite information from significant events like Helene or local phenomena such as urban flooding in Southern Illinois.

Researchers possess a solid grip on the typical patterns of stable river systems; however, extreme conditions alter the dynamics. Hence, within her lab, Masteller aims to ascertain the extent to which severe weather can impact a river system before it deviates from the norm.

During Helene, all rivers in North Carolina experienced the “unprecedented flood.” Essentially, it was “the largest flood the gauge recorded since its installation,” she remarks. Some rivers drastically altered their courses following the floods in North Carolina, while others exhibited far fewer changes.

Masteller seeks to comprehend why certain rivers demonstrate resilience, maintaining their deep channels and adhering to their original courses after significant flooding, in contrast to others that end up expanding and changing direction.

Accurately forecasting which rivers will react to these extreme environmental events is a burgeoning area in the field, she notes. She has a few hypotheses currently undergoing peer scrutiny. Regarding river resilience, she is investigating if the frequency of flooding influences outcomes since more disturbed riverbeds may struggle to stabilize between flood occurrences. Mudslides could also play a role as “an added factor that may increase the river’s sensitivity,” she states. Research conducted by Masteller and her colleagues on these geomorphological mechanisms will be the subsequent step in the years to come.

Exploring the “why” behind shifting rivers and other “earth surface hazards” faced by humans necessitates acknowledging the chaotic, winding movements of the earth and investigating the forces that drive those motions. “Comprehending that is the foundational goal of much of the work we undertake.”

Crafting sutures from snake teeth

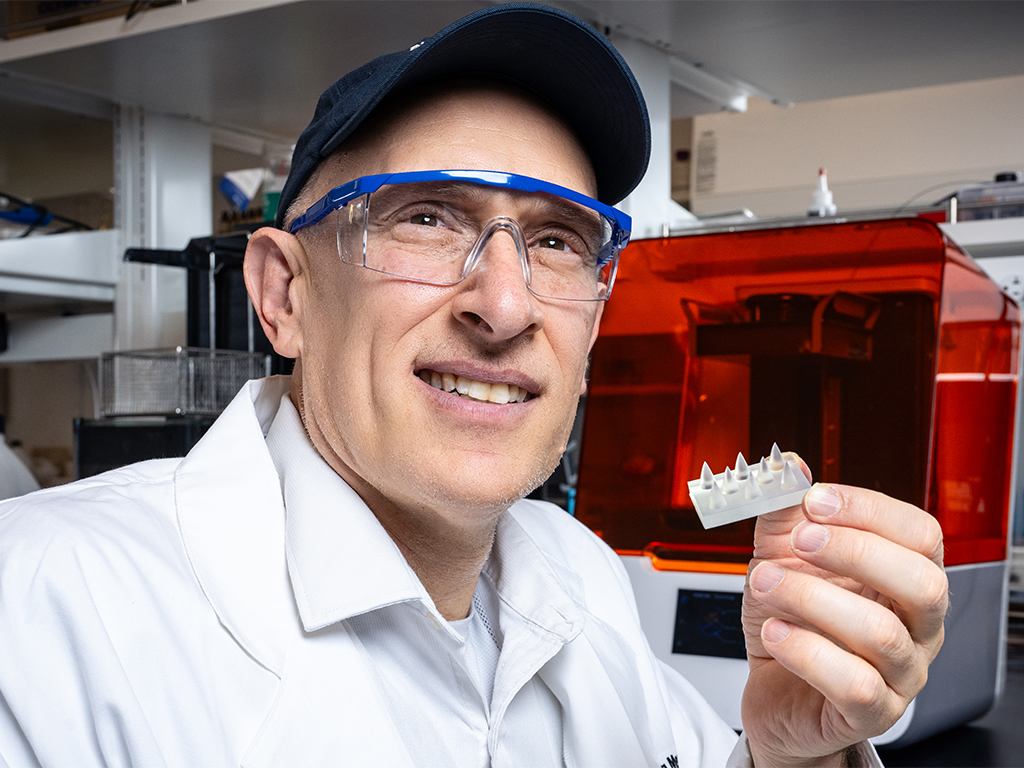

As often happens among a cohort of scientists, the scholars and students in Guy Genin’s biomedical engineering laboratory began discussing one day how a velociraptor might hunt its prey, which flowed into an extraordinary dialogue regarding how contemporary predators capture their prey, ultimately leading to an even more astonishing revelation: a novel method to assist individuals in recovering from tendon surgery.

You might not expect that a depiction of a dinosaur tearing into flesh would spark ideas in biomedical design. However, Genin, the Harold and Kathleen Faught Professor of Mechanical Engineering at the McKelvey School of Engineering, can derive unexpected inspiration from nature.

Rotator cuff procedures have a notorious failure rate; between 20%–94% of surgeries fail, predominantly due to sutures slipping through tendons at “grasping points.” These grasping points are critical, and current medical designs resemble straight-edged shark teeth. This draws us back to the discussion of predators, not all of which “tear” into their prey. During the dinosaur conversation in Genin’s laboratory, a postdoctoral fellow named Lester Smith (now a professor at Indiana University) highlighted that pythons grasp and drag their prey without tearing the flesh.

“Pythons truly grip their prey; they asphyxiate their quarry and then swallow them,” Genin cheerfully remarks. His cheery demeanor reflects the outcome of this discussion—a new device employing python-tooth-like hooks to support the sutures.

“Even when the force is spread out, the maximum force that each point can endure is greater with a curved tooth than with a straight tooth.”

Guy Genin

These teeth are designed with a curvature that redirects the pressure downward, pulling that delectable mouse flesh toward the gum line rather than tearing it away. Just like a snake can effectively pull, really pull its prey into its mouth without damaging it, this innovative design of “python-tooth sutures” can withstand the continuous pull of the tendon while engaging the shoulder. “Even when the force is distributed, the maximum force that each point can bear is increased with a curved tooth compared to a straight tooth,” Genin explains.

Genin and his team are set to advance python-tooth sutures through a lengthy commercialization journey ahead. And this is merely the beginning of his numerous projects. Genin, who is endlessly intrigued by the mechanical forces influencing the human body—right down to the movements of cells and how those forces impact a cell’s operation—is a principal investigator in a new international consortium focused on whether cells can convey information to one another through tiny vibrations in the protein scaffolding surrounding them. Positive vibes all around.

The garden as an artistic space

Artist Juan William Chávez embraces a straightforward concept that can significantly enhance an individual’s emotional well-being: Envision a garden as an art studio.

“The garden is one of the most distinctive places where you can engage all the senses,” states Chávez, a lecturer at the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts.

Chávez operates a nonprofit organization known as Northside Workshop, where he and his partners utilize art, a chemical-free educational garden, and a bee sanctuary as a platform for community-building, self-expression, and conservation. His work is currently highlighted this spring in the Kemper Art Museum’s exhibit Seeds: Containers of the World to Come.

“Our garden specifically aims to replicate natural processes,” he mentions. In that informal, occasionally unruly environment, individuals often find themselves emotionally opening up and contemplating their connection to the natural world. “They’re going to narrate their stories through what they cultivate and their relationship with nature,” Chávez explains.

The Northside Workshop includes an art studio and an acre of land around the building, serving as an illustration of permaculture gardening—a gardening method that mimics more natural conditions. For several years, the group has conducted workshops emphasizing the significance of native bees, which are responsible for about 80% of all pollination of wild flowering plants.

The more local gardeners can provide a suitable habitat for these bees, the healthier regional ecosystems can become. However, Chávez underscores that many individuals will need to rethink their perspective on gardening. “Everyone has access to some form of green space, and typically when we view green space, we associate it with chores or maintenance,” he explains.

Chávez advocates for relinquishing the urge to control and embracing the natural progression of what occurs in the garden. He has personally experienced the advantages of this approach. “My back appreciates it,” he states, recalling that his previous studio was largely desk-oriented. “The desk-bound individual is de-stressing and stretching their legs.”

Besides the physical benefits, he values the introspection that gardening facilitates. “I feel a connection to my ancestors,” shares Chávez, who has Peruvian heritage.

The Northside Workshop provides another advantage: an internship program at WashU, where students learn about permaculture gardening. The interns tend to the garden in amicable silence, as gardening compels them to disconnect from their phones, remain present, and ground themselves.

“Suddenly, nature begins to reveal itself, and nature serves as healing,” Chávez remarks.

The post Inspired by nature appeared first on The Source.