“`html

ALPENA, Michigan—Ken McQuarrie was raised just two blocks from Thunder Bay, in Alpena, where his father and uncles were involved in diving. One of his uncles delved into shipwreck explorations in the bay.

However, McQuarrie never acquired diving skills, and he subsequently enrolled at Alpena Community College following his high school graduation. He began working to support his family after welcoming his first son at 17 and a second at 22.

One day, while his youngest boy was attending high school, McQuarrie visited a career expo. One of the exhibits caught his attention: an underwater remotely operated vehicle, or ROV, displayed in a large aquarium. Beside it stood David Cummins, an instructor at ACC and counselor for the college’s Marine Technology Pathways initiative.

“I grabbed the remote, and David remarked, ‘You’re quite skilled at this. Have you ever considered working with underwater robots?’” McQuarrie recalled.

McQuarrie enrolled in a two-year program. One day in 2015, after training in the harbor, he encountered University of Michigan archaeologist John O’Shea, who was returning to the marina following a research expedition on the Alpena-Amberley Ridge, an underwater ridge extending from Alpena to Amberley, Ontario. He was assessing potential ancient caribou hunting grounds, located on what would have been dry land 8,000 to 11,000 years ago.

“I volunteered to assist him,” McQuarrie expressed. “I never required recognition in any publications or anything similar. I just wanted to be a part of it.”

McQuarrie spent his first day collaborating with O’Shea’s crew drawing on his internship background on research vessels in the Gulf of Mexico, deploying the ROV and controlling its tether. This tether, a cable providing both power to the ROV and communication between the robot and boat, is the most crucial aspect of the task.

After that initial day, O’Shea offered McQuarrie a contracting role.

“I vividly remember receiving that first paycheck emblazoned with the University of Michigan. I’ve been a U-M enthusiast my entire life. The chance to work with the University of Michigan and Dr. O’Shea—that was a dream realized.”

Since the project commenced in 2008, O’Shea’s team has identified 72 probable locations. To date, twelve of these have been verified, encompassing caribou hunting sites, settlements, and stone caches. The findings have fostered an ongoing underwater archaeology research initiative, involving community volunteers, college and high school educators, and students, transforming the perspective of people from this isolated, northern Michigan region regarding their own heritage.

Science within the sanctuary

O’Shea began investigating the ridge utilizing maps of the lake bottom produced by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association in 2008. NOAA designated the waters of Thunder Bay as a National Marine Sanctuary in 2000; Lake Huron in this area is scattered with historically important shipwrecks from the 19th and 20th centuries. O’Shea got involved as, during a timeframe of low water levels, individuals were plundering the shipwrecks.

However, during the lake floor surveys, O’Shea suspected that another narrative might be unfolding. He recognized that the Alpena-Amberley Ridge would have served as a dry corridor linking northern lower Michigan to southern Ontario just after glaciers retreated from the Michigan area, coinciding with the formation of the Great Lakes as we recognize them today. His prior research indicated that hunters frequently utilized natural land formations such as these as strategic points to hunt migratory caribou (which are closely related to reindeer).

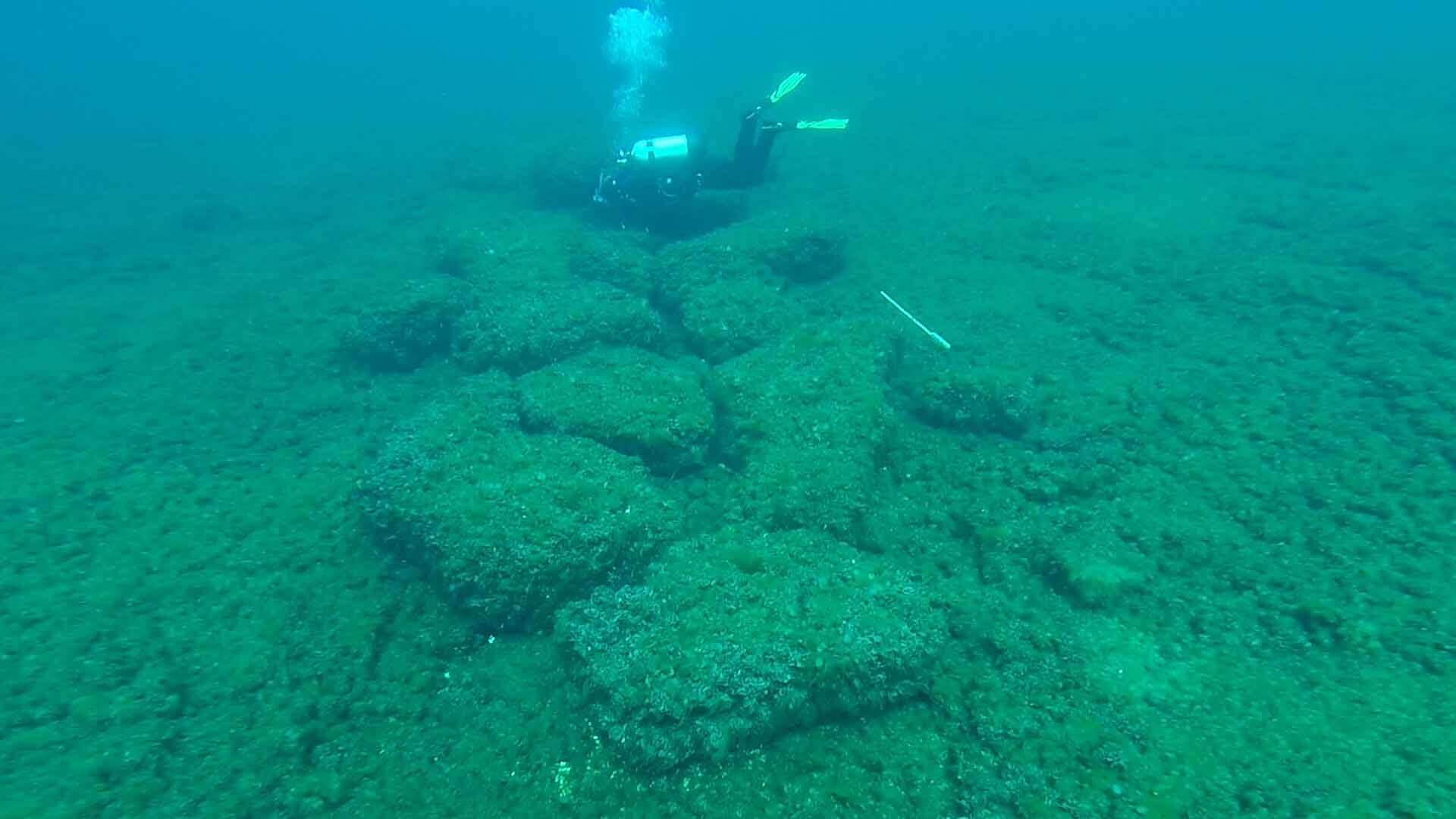

With funding from the National Science Foundation, O’Shea and his research team commenced scanning the ridge and began noticing unusually shaped clusters of rocks—enough for a person to hide behind. They also uncovered stone lines that natural currents or ice could not have formed. Their conclusion? Man-made hunting blinds and drive lanes established between 8,000 and 11,000 years ago for caribou hunting.

To disseminate his findings, O’Shea frequently delivers presentations at NOAA’s Great Lakes Maritime Heritage Center, the visitor center associated with the Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary. At the start of the winter term each academic year, O’Shea visits Alpena High School’s science teacher Erich Schlueter.

Schlueter teaches a course titled Science in the Sanctuary, in which students investigate various kinds of science occurring at the Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary. O’Shea presents a lecture on his underwater archaeology, and together with Schlueter, they strive to engage the students in the most compelling way they can: through a video game.

The game is a simulation O’Shea devised with assistance from Bob Reynolds of Wayne State University. Reynolds specializes in the application of artificial intelligence within games, and O’Shea required a method to predict where hunting blinds might be situated along the 90-mile-long, 9-mile-wide ridge.

Reynolds collaborated with O’Shea to create a game featuring artificially intelligent caribou, allowing high school students to track caribou as they wander the ancient land bridge using a virtual reality headset and controllers. In Schlueter’s classroom, students can immerse themselves in the virtual reality of what Lake Huron resembled 10,000 years ago.

“““html

any time they desire.

As the learners navigate the ancient terrain, they can observe the locations of previously uncovered hunting structures and speculate on additional spots that may be appropriate. Upon identifying a promising area, students log the coordinates of the site, which O’Shea and his team can then validate in actuality, on the lake.

“We provided them not merely the digital environment, but also the sonar data and the mapping results of the bathymetry, so they’re integrating all these various information sources,” O’Shea remarked. “At the end of the year, we take the five top forecasts, and we actually venture out to verify them. In the first year we conducted this, they indeed discovered a new site.”

A season of discovery

During his summer days with the team, McQuarrie stated there were instances when the crew was 45 miles offshore from Alpena, and the water appeared as calm as glass—no ripples, no waves. On another occasion, McQuarrie utilized his drone to record the vessel, with no land visible. Underwater, McQuarrie’s responsibility was to maneuver the ROV over prospective hunting locales. Once identified, O’Shea and his team would don their gear and dive down, following the robot’s tether to examine the lake floor.

Caribou and reindeer have a peculiar behavior where they tend to follow linear patterns, O’Shea noted. Ancient hunters—and their modern equivalents—are aware of this.

“Today’s reindeer herders in Siberia, wanting to direct their herd to a specific area, merely cut brush and lay down lines on the ground. That’s sufficient to guide the direction the animals take,” O’Shea explained. “Hunters understood that too, and they would create linear formations so that as the animals migrate, they would naturally follow that path, funneling them into a designated kill zone.”

This generally simplifies the identification of these hunting sites, O’Shea claimed. McQuarrie would have been on the lookout for large stones aligned in a lengthy, straight arrangement culminating in a V-shaped hunting blind. The hunting blind served both to conceal hunters from the caribou’s sight and to direct them through a restricted exit towards awaiting hunters.

This specific arrangement of rocks—in curving lines and v-shaped configurations—is unlikely to form naturally, nor in the precise areas most advantageous for intercepting migrating caribou. This assists researchers in selecting which locations to visually assess through dives and sampling, O’Shea indicated. To confirm that a structure or site was constructed by humans, the researchers employ a gold standard: artifacts or other remnants of cultural activity.

Surrounding numerous sites, researchers have discovered not only small tools, blades, and other implements that would have been utilized for hunting, but also flakes of obsidian. Obsidian did not originate in the Great Lakes area, O’Shea asserts, and lab analysis of the recovered flakes verified them to be from central Oregon—only reaching ancient hunters in the Great Lakes region through a trading network.

“What sets these sites apart from terrestrial archaeology is that the land form hasn’t been altered since it went underwater,” O’Shea remarked. “It resembles your own Pompeii. Unlike terrestrial sites, where everything is rearranged, and farmers shift stones or construct roads, the underwater artifacts remain exactly where they were left. We can discern where the hunting sites were versus where the camps were, providing a much clearer picture of the entire landscape as it once was than one would find on land.”

The configuration of the sites is familiar to McQuarrie, who is a deer hunter and was raised in a hunting family.

“Observing these lines of rocks and knowing how even modern hunters use trails through forests and hinge-cut trees to guide deer to their feeding areas,” McQuarrie expressed. “Who knows—they might have utilized those rocks alongside trees or shrubs, which have probably vanished after 9, 10, or 11,000 years.”

Exploring deeper waters

Almost all the sites examined by O’Shea’s research team lie within the depth range of 70 to 130 feet. These represent locations, probably established and utilized around 9,000 years ago, as the glaciers that blanketed the Great Lakes region were receding and gradually filling the Lake Huron basin.

O’Shea has recently been awarded one of five Klinsky Expedition projects, an initiative established by U-M alumnus Steven Klinsky to advance pioneering archaeological research at the University of Michigan. For the Klinsky “moonshot” research, O’Shea’s team has commenced the search for sites at greater depths. These locations would be the earliest, likely constructed around 11,000 years ago, when expansive segments of the Lake Huron floor would have been available for habitation.

For McQuarrie, who presently resides near Lansing, the research experience provided him a glimpse into what the area around Alpena looked like during a timeframe far older than the epoch when ships met their fate against the perilous shores and landscapes of Thunder Bay—and scratched a similar itch that began when he observed his family preparing to explore nearby lakes.

“I felt honored on the first day they permitted me on the vessel. I’m honored to discuss it today. It has been a significant highlight in my life,” McQuarrie reflected. “The experiences I’ve had and the sights I’ve encountered, broadening my understanding, it’s been incredible.”

He mentioned that he continues to access the bathymetric imagery of the Lake Huron floor to exhibit to others the Alpena-Amberley Ridge and demonstrate that Lake Huron was once two distinct lakes. He highlights where he explored the lake bed with O’Shea, searching for traces of humans from ages past—45 miles from Alpena and 45 miles from the Canadian border.

McQuarrie asserts that it’s work that also sets Alpena apart from the rest of the state.

“There are no highways traversing here. It’s not a popular destination like Traverse City or Petoskey. Northeast Michigan is somewhat tranquil compared to the western side of the state,” McQuarrie stated. “What Dr. O’Shea has accomplished for the Alpena community, simply by sharing this knowledge regarding his research, along with the insights that the Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary and NOAA have unearthed, illuminates a whole new aspect of northeast Michigan.”

“`