“`html

It’s alluring to assume that, thanks to our sophisticated electric illumination and indoor sleeping quarters, humanity has transcended the natural effects of daylight on our rest patterns.

However, fresh discoveries from the University of Michigan demonstrate that our circadian rhythms remain deeply connected to the seasonal transitions in light.

“Humans are intrinsically seasonal, albeit we might be reluctant to acknowledge this in our contemporary context,” stated study author Ruby Kim, a postdoctoral assistant professor in mathematics at U-M. “Day length and the quantity of light we receive significantly impact our biology. The research illustrates that our biologically ingrained seasonal timing influences our ability to adapt to alterations in our daily routines.”

This revelation may pave the way for innovative methods to explore and comprehend seasonal affective disorder, a form of depression linked to seasonal variations. It might also uncover new domains of research concerning various health challenges associated with the synchronization between our sleep patterns and circadian rhythms.

For instance, researchers—including the study’s leading author, Daniel Forger—have previously demonstrated that our moods are significantly influenced by the degree of alignment between our sleep patterns and circadian rhythms.

“This study holds great potential for future research,” Kim remarked about the newly published findings in the journal npj Digital Medicine. “It could have broader implications for mental health concerns, including mood and anxiety disorders, as well as metabolic and cardiovascular issues.”

The investigation also revealed a genetic aspect to this seasonality in humans, which might clarify the wide differences in how individuals respond to fluctuations in day length.

“Some individuals may find it easier to adapt, while for others, it could be much more challenging,” noted Forger, a U-M professor of mathematics and director of the Michigan Center for Applied and Interdisciplinary Mathematics.

Understanding this genetic aspect will assist researchers and healthcare providers in pinpointing where individuals stand on this spectrum, but reaching that point will require additional time and effort. Currently, this study serves as an initial yet significant stride toward redefining our understanding of human circadian rhythms.

“Many individuals tend to perceive their circadian rhythms as a singular clock,” Forger explained. “What we’re demonstrating is that there isn’t just one clock, but rather two. One is attempting to track sunrise while the other is monitoring sunset, and they are communicating with one another.”

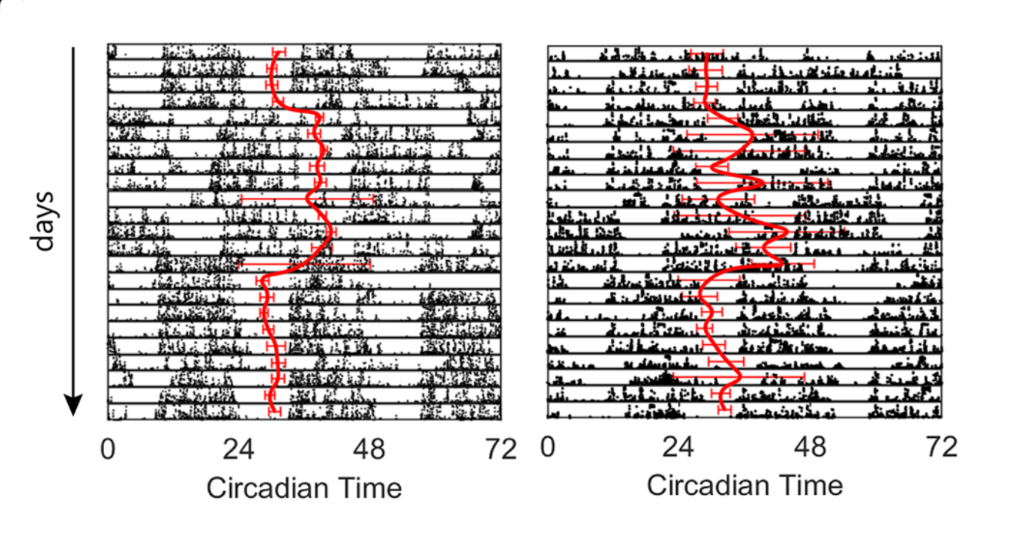

Kim, Forger, and their colleagues discovered that people’s circadian rhythms were attuned to the seasonality of light by analyzing sleep data from thousands of individuals equipped with wearable health trackers, such as Fitbits. The participants were all medical residents engaged in a year-long internship and enrolled in the Intern Health Study, sponsored by the National Institutes of Health.

Interns are shift workers with schedules that fluctuate frequently, resulting in corresponding changes in their sleep patterns. Additionally, these schedules often conflict with the natural rhythms of day and night.

The observation that circadian rhythms in this demographic displayed seasonal dependencies presents a compelling case for just how ingrained this trait is in humans, which is not wholly surprising, according to the researchers.

Previous studies on fruit flies and rodents provide substantial evidence that these animals have seasonal circadian clocks, Forger stated, and other scientists have speculated that humans’ circadian clocks may function similarly. Now, the U-M team has presented some of the strongest validation of this notion through their analysis of how seasonality manifests in a significant, real-world study.

“I believe it ultimately makes a lot of sense. Brain physiology has been evolving for millions of years to monitor dusk and dawn,” Forger expressed. “Then industrialization arrives in the blink of an evolutionary eye, and we find ourselves still striving to keep pace.”

Participants in the Intern Health Study also supplied saliva samples for DNA analysis, allowing Kim and Forger’s team to incorporate a genetic dimension into their research. Genetic investigations led by other scientists have identified a particular gene critical for how the circadian clocks of various animals adapt to seasonal variations.

Humans possess this gene, enabling the U-M team to pinpoint a small fraction of interns exhibiting slight variations in this gene’s genetic structure. For that subset, shift work proved more disruptive to the synchronization of their circadian clocks and sleep patterns across seasons.

Again, this leads to numerous questions, particularly concerning health ramifications and the effects of shift work on different individuals. However, these are inquiries the researchers aim to investigate in the future.

“`