Prior to exploring the woods, a local park, or even your own backyard, stay vigilant for mosquitoes and ticks, which can act as vectors or carriers for pathogens responsible for diseases.

In this discussion, specialists Solny Adalsteinsson and Katie Westby detail the threats these pests present to both you and your animals and offer tips on how to remain secure this summer. Adalsteinsson focuses on tactics to mitigate the spread of tick-borne illnesses, while Westby investigates the ecology and evolution of container-breeding mosquitoes—specifically those that reproduce in refuse and flower pots. Both are staff scientists at the Tyson Research Center, part of Washington University in St. Louis’ expansive 2,000-acre environmental field station located in west St. Louis County.

In what ways does the Midwest differ from other regions of the U.S. concerning tick and mosquito populations and potential illnesses?

Adalsteinsson: Lyme disease is the most prevalent vector-borne illness across the U.S. However, we don’t encounter much Lyme disease here. Instead, the majority of illnesses you might be exposed to are those carried by the lone star tick and the American dog tick. These include ehrlichiosis and rickettsiosis, which may show symptoms such as headaches, fever, chills, nausea, rashes, and muscle pains.

One condition that is gaining recognition — and is notably more of a threat here and in the southeastern U.S. — is an allergic reaction triggered by a lone star tick bite. It’s referred to as Alpha-gal syndrome, which causes individuals to develop allergies to mammalian meats and other products derived from mammals, such as milk, butter, and certain medications.

The Bourbon virus and Heartland virus have also emerged in Missouri within the past 10-15 years, and our understanding of them remains limited. Thus, we are conducting collaborative research with virologists and wildlife veterinarians to identify the species involved in the transmission of these pathogens and the ecological factors that influence their presence.

Westby: In Missouri, the mosquito situation is quite akin to what you would encounter further east. Fortunately, at present, the U.S. reports relatively few instances of mosquito-borne diseases in humans. Every year, we see cases of West Nile virus, which is endemic and found throughout the country. A significant issue we face in Missouri, however, is heartworm transmission via mosquitoes, which poses a serious problem for our pets.

How can you effectively prevent tick and mosquito bites?

Westby: Utilize permethrin and DEET. We also recommend wearing lighter clothing and protective coverings. Nonetheless, mosquitoes can penetrate thin fabrics.

Adalsteinsson: Permethrin treatments not only repel insects and ticks but can eliminate them upon contact. These products should be applied to clothing or gear and allowed to dry completely. In Missouri, there isn’t a time that isn’t tick season. Thankfully, ticks can’t fly or jump; they’re not found in trees.

Consider establishing a barrier between your skin and the pests to give yourself more time to notice them before they bite. This can involve wearing closed-toe shoes, long socks, and tucking your pants into your socks or even using gaiters. After spending time outside, be sure to thoroughly inspect yourself in every nook and cranny you can think of.

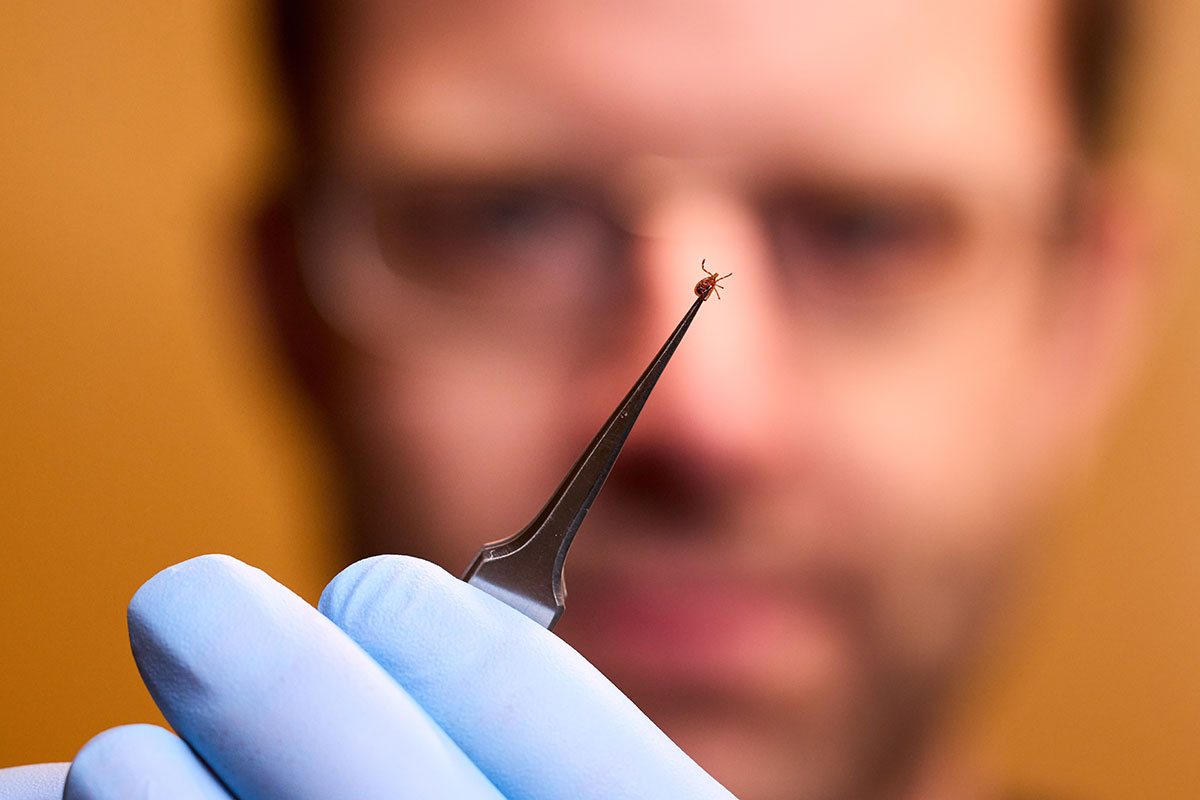

What steps should you take if you discover a tick attached to your skin?

Adalsteinsson: First and foremost, remain calm because not all ticks harbor a pathogen that could harm you. Typically, it is a small fraction of ticks that carry something that might cause illness. If they do have a pathogen, the likelihood of transmission increases the longer they remain attached.

I suggest utilizing fine-tipped tweezers to grasp as close to the skin’s surface as possible to fully remove the tick. After removal, clean the bite area with soap and water.

You might also consider freezing the tick in a Ziploc bag, labeling it with the date you discovered it and its location on your body. Laboratories can analyze the tick later. Generally, I wouldn’t advise doing this unless you actually fall ill. Otherwise, you might end up worrying for no reason.

What ecological role do mosquitoes play in our ecosystems?

Westby: I prefer to turn this question around as it stems from a distinctly human viewpoint. Just because we dislike mosquitoes doesn’t imply they require a human ‘purpose.’ They exist simply because they exist. If you were a virus spread by mosquitoes, you would certainly be disheartened if they vanished.

The mosquitoes that carry diseases to humans in urban settings don’t hold significant ecological importance. They are seldom consumed by bats. In their aquatic environments, they may be preyed upon by dragonflies and other mosquito larvae, but they do not contribute substantially to our urban ecosystems. Conversely, the mosquitoes found in wooded areas are consumed by bats and other animals as part of the food chain and do fulfill a role in the forest ecosystem. They also act as minor pollinators.

The post How to stay safe from ticks and mosquitoes in the Midwest appeared first on The Source.