“`html

In the late 1990s, a Harley-Davidson official named Donald Kieffer became the general manager of an engine factory near Milwaukee. The legendary motorcycle manufacturer had crafted a well-regarded resurgence, and Kieffer, who acquired manufacturing skills on the shop floor, had been integral to it. Now, Kieffer aspired to enhance his facility. So he organized for a prominent Toyota executive, Hajime Oba, to visit.

The encounter didn’t unfold as Kieffer had anticipated. Oba toured the plant for 45 minutes, sketched the layout on a whiteboard, and proposed one minor adjustment. As a senior-level manager, Kieffer assumed he needed to implement sweeping improvements. Instead, Oba queried him, “What issue are you endeavoring to resolve?”

Oba’s message was nuanced. Harley-Davidson had a competent plant that could improve, but not by enforcing grand, authoritative strategies. The crucial element was to address workflow problems that employees could recognize. Even a small adjustment can yield significant outcomes, and, in any case, a modestly beneficial tweak is preferable to a large, formulaic overhaul that disrupts operations. Thus, Kieffer embraced Oba’s suggestion and began enacting targeted, practical modifications.

“Organizations are fluid environments, and when we attempt to impose a rigid, static framework on them, we suppress all that fluidity,” states MIT management professor Nelson Repenning. “And the waste and chaos that result are a hundredfold more costly than people expect.”

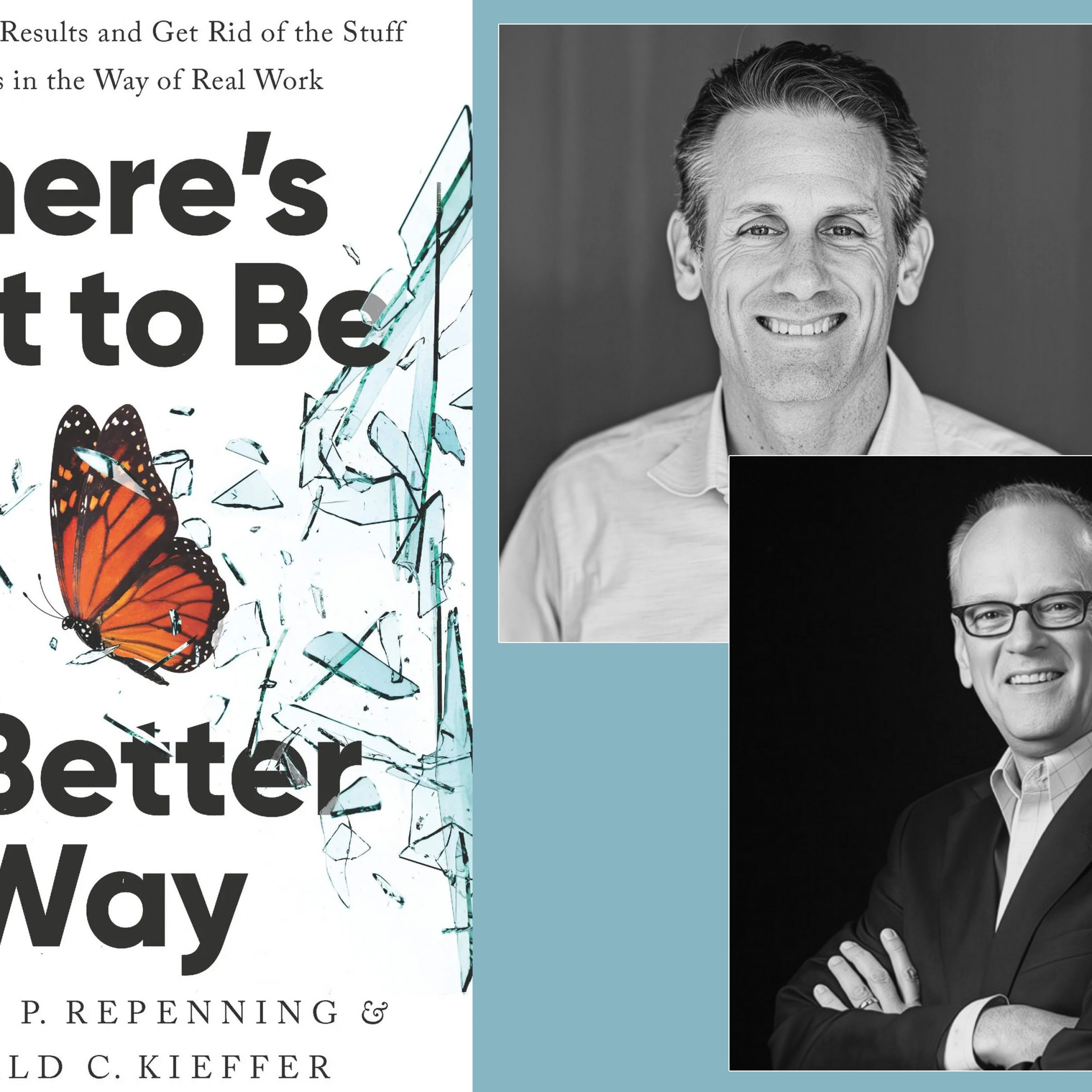

Now, Kieffer and Repenning have authored a book on adaptable, reasonable organizational enhancement, “There’s Got to Be a Better Way,” published by PublicAffairs. They refer to their methodology as “dynamic work design,” aimed at assisting firms in refining their workflows — and preventing individuals from exacerbating issues through overconfident, one-size-fits-all solutions.

Kieffer adds: “Our guidelines focus on how work is structured. Not on how leaders must behave, but on how to design human work and facilitate transformation.”

One partnership, five principles

This book is the result of a long-term partnership: In 1996, Kieffer first encountered Repenning, who was then a new member of the MIT faculty, and they quickly realized they shared similar views on managing work. By 2008, Kieffer also became a lecturer at the MIT Sloan School of Management, where Repenning is now a distinguished professor of system dynamics and organization studies.

The duo began offering executive education courses together at MIT Sloan, frequently collaborating with firms facing challenging dilemmas. In the 2010s, they extensively worked with BP executives following the Deepwater Horizon incident, discovering ways to merge safety priorities with other operational aspects.

Repenning specializes in system dynamics, a field developed by MIT that focuses on how different parts of a system interact. In a company, making isolated adjustments may further destabilize the overall system. Instead, managers must understand the broader dynamics and acknowledge that a company’s challenges are usually not its personnel, as most employees perform comparably when burdened by a flawed system.

While many management systems are designed to prescribe fixed actions in advance — such as eliminating the bottom 10 percent of employees annually — Repenning and Kieffer contend that a firm should empirically analyze itself and derive enhancements from those findings.

“Managers often lose sight of how work genuinely gets accomplished,” Kieffer notes. “We help managers connect with real-time work to observe the challenges people face, aiding them in solving issues and discovering new methods of working.”

Over time, Repenning and Kieffer have encapsulated their conceptualizations of work design into five principles:

- Solve the appropriate problem: Employ empirical methods to create a blame-free outline of issues to tackle;

- Structure for exploration: Enable employees to see how their tasks integrate into the broader context and assist in improving processes;

- Connect the human network: Ensure the right information flows from one individual to the next;

- Regulate for continuity: New tasks should only enter a system when there is capacity to manage them; and

- Visualize the workflow: Establish a visual technique — such as a whiteboard with sticky notes — for mapping operational tasks.

No mugs, no t-shirts — just open your eyes

Implementing dynamic work design in any organization may sound straightforward, yet Repenning and Kieffer highlight that numerous factors hinder effective execution. For example, company leaders might be inclined to select technology-driven solutions when simpler, more cost-effective fixes are available.

Indeed, “resorting to technology prior to correcting the foundational design risks squandering resources and embedding the original issue even deeper in the organization,” they explain in the book.

Furthermore, dynamic work design is not an inherent solution but rather a means of identifying a specific resolution.

“One concern that keeps Don and me awake at night is a CEO reading our book and thinking, ‘We’re going to become a dynamic work design company,’ and printing t-shirts and coffee mugs and hosting two-day conferences where everyone signs the dynamic work design poster, and assessing everyone weekly on how dynamic they are,’” Repenning remarks. “Then you’re being quite rigid.”

After all, organizations evolve, and their requirements transform. Repenning and Kieffer urge managers to continually analyze their firm’s workflow to remain attuned to their needs. In fairness, a segment of managers does engage in this practice.

“Most individuals have experienced fleeting instances of effective work design,” Repenning states. Building on that, he asserts that managers and employees can perpetuate a process of enhancement that is practical and rational.

“Start modestly,” he continues. “Select one issue you can address in a couple of weeks and resolve that. In most cases, with open awareness, there’s low-hanging fruit. Identify the areas where you can succeed, and make incremental changes rather than overwhelming shifts. For senior executives, this is challenging. They are accustomed to grand gestures. I advise our executive education students that it will feel uncomfortable at first, but this is a far more sustainable route to advancement.”

“`