“`html

Arts & Culture

From ‘joyful’ to ‘sensually engaged’ to ‘fervently angry’

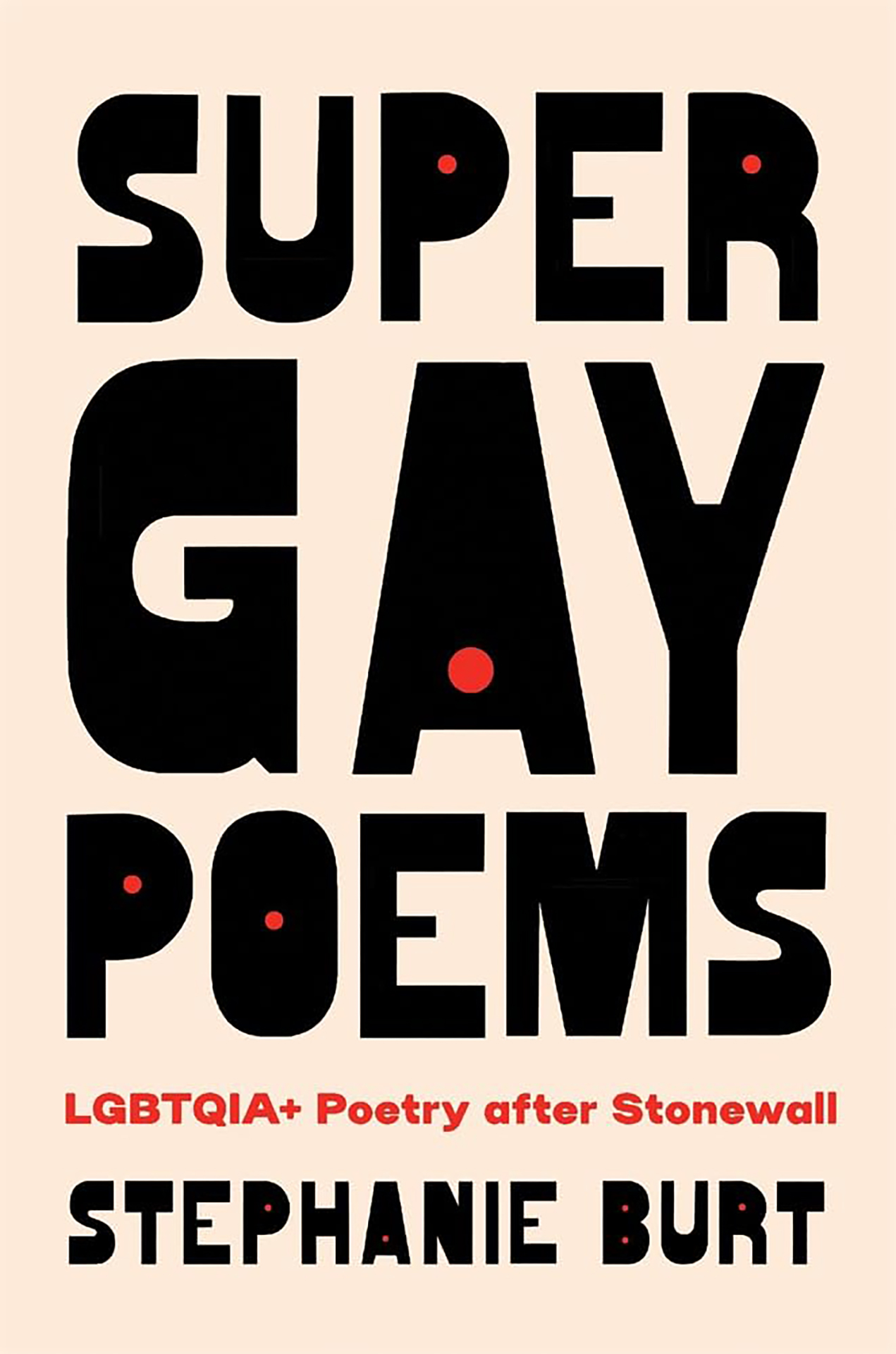

Stephanie Burt’s latest compilation features 51 creations by queer and trans poets across generations

Niles Singer/Harvard Staff Photographer

As Stephanie Burt perceives it, queer lyric poetry reflects the nuances of queer existence. She provides various instances in “Super Gay Poems: LGBTQIA+ Poetry After Stonewall,” a new collection of 51 creations by queer and trans poets from the past 55 years.

“I selectively chose poems I admire and aspired to write an essay about,” stated Burt, Donald P. and Katherine B. Loker Professor of English, who complemented each piece with an original essay offering analysis and historical context. “I sought stylistic diversity, from succinct to lavish, formal-rhymed to free and chaotic, unusual-and-challenging to seemingly clear. I also sought emotional diversity, from joyful to sensually engaged to fervently angry, quietly inquisitive, resolved, sorrowful, inviting, bashful, and extroverted.”

Burt’s selected poets span across generations, from Frank O’Hara (1926-1966) to Logan February (born in 1999), addressing significant moments in contemporary queer history — from Paul Monette’s “The Worrying” (1988) reflecting on the HIV/AIDS crisis, to Jackie Kay’s “Mummy and donor and Deirdre” (1991), which delves into the heightened visibility of queer families.

This anthology also showcases a broad geographic spectrum, from Puerto Rican writer Roque Salas Rivera to Singaporean writer Stephanie Chan. Some names, like Audre Lorde and Adrienne Rich, will be recognizable to many readers, while others may present new findings.

In this edited discussion with the Gazette, Burt shares her thoughts on transformations in the poetry sphere, the excitement of discovering new voices, and the capacity of poetry to encapsulate historical moments.

Could you elaborate on the concept of time in LGBTQIA+ poetry?

Many of us were raised with a distinct, normative series of expectations regarding life’s progression: You are a child, then a teenager, then an adult, and finally, you age. You socialize with same-sex friend groups, then you date, become ‘serious,’ marry, and ideally raise 2.6 children.

Often, queer time, as captured and discussed in queer poetry, operates differently. You don’t “mature” if maturing means forsaking your close same-sex bonds in favor of heteronormative dating. Or perhaps, as an adult, you find energy from the thrilling gatherings adults are expected to abandon. Alternatively, you might navigate puberty twice and embody (or behave like) a bewildered, excited adolescent as an adult. Even if you eventually become monogamously attached to a consistent partner for decades, as some of my poets did, the poetry reflecting that bond manifests in a unique manner: It may feel more hard-earned or seem like a past secret.

What transformations do we observe in LGBTQIA+ poetry following the 1969 Stonewall Uprising?

After Stonewall, there is a notable increase in individuals coming out. More people openly celebrate long-term relationships. Many start families, nurturing the next generation. In the 1970s, lesbian poets honor women-only or lesbian-exclusive spaces; subsequently, this changes. During the 1980s and early 1990s, an entire generation — particularly, although not solely, gay men — lost a substantial portion of their friends to HIV/AIDS, which continues to be lethal in many parts of the world but appears less frequently in poetry.

Throughout the 2010s, individuals emerged as trans or nonbinary. Additionally, in the 2000s and 2010s, a growing number of people from the Global South came out and penned poems about how their diverse identities and forms of belonging intersect. At times, they feel welcomed in their hometowns, while at other times — as illustrated by Logan February, whose poem “Prayer of the Slut” (2020) is featured in the book — they do not, and cannot.

Did you make any new discoveries while compiling this anthology?

Indeed, I had never previously encountered Cherry Smyth, whose poem “In the South That Winter” (2001) is part of this work, nor Logan February. I hadn’t examined Melvin Dixon (“The Falling Sky,” written 1992, published 1995), or Judy Grahn (“Carol, in the park, chewing on straws,” 1970) with enough diligence until this compilation provided me with the opportunity to reassess their writings.

Do you perceive poetry as a means of documenting LGBTQIA+ history?

All artistic forms record history since every artwork originates from historical moments. I selected the poems in this collection because I cherished them all, but certain aspects of global queer history in English are absent because I didn’t or couldn’t locate remarkable poems about them: queer liberation in the Republic of Ireland, for instance, or the connection between the Filipino diaspora and Filipino/a/x bakla identities. For the latter, I recommend Rob Macaisa Colgate’s incredible book, published after “Super Gay Poems” was completed.

I happily — yet also regretfully — included verses linked to significant historical events, such as Paul Monette’s AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power poem [“The Worrying”], which warrants a fresh examination these days. However, some of my favorite poems have no relation to major public history segments — they create aesthetic havens from it or alternatives to it. May Swenson’s “Found in Diary Dated May 29, 1973” (first book publication 2003), for instance, serves as an allegory of lesbian love through plant roots. You can connect it to history if you wish, but that’s not the primary invitation of the poem.

What do you hope readers will glean from this anthology?

New favored poets! New cherished poems! And an awareness of the queer, trans, ace, intersex, pan, and various other possibilities available today, even amidst this challenging time for many of us — possibilities encompassing fears and disasters but also resilience, community, solidarity, and joy.

“`