“`html

Motorists can now assess the greenhouse gas emissions of various vehicles based on dimensions, applications, powertrain category, and even geography

Selecting a more electrified vehicle will lessen motorists’ greenhouse gas emissions, no matter their location in the contiguous United States, as per a fresh study from the University of Michigan.

This examination is the most thorough to date, according to the authors, providing motorists with emissions estimates per mile traveled across 35 diverse combinations of vehicle categories and powertrains. This encompassed conventional gasoline pickups, hybrid SUVs, and fully electric sedans among numerous other configurations.

Indeed, the research team developed a complimentary online calculator allowing drivers to gauge greenhouse gas emissions rooted in their vehicle type, driving habits, and local environment.

This research, published in the journal Environmental Science & Technology, received support from the State of Michigan Department of Labor and Economic Opportunity as well as the U-M Electric Vehicle Center.

“Vehicle electrification is a critical approach for combating climate change. Transportation contributes to 28% of greenhouse gas emissions, and it’s essential to diminish these to mitigate future climate consequences such as flooding, wildfires, and droughts, which are becoming more intense and frequent,” remarked Greg Keoleian, the principal author of the new study and a professor at the U-M School for Environment and Sustainability, or SEAS.

“Our aim was to assess the cradle-to-grave greenhouse gas reductions resulting from the electrification of vehicles compared to a baseline of gasoline vehicles.”

Besides aiding drivers in comprehending their emissions, Keoleian and associates stated that this data will also be beneficial for the automotive sector and policymakers.

While EVs face challenges from a federal policy perspective, the industry remains devoted to electrification, Keoleian stated. For instance, Ford Motor Co. recently unveiled plans for a more cost-effective electric vehicle platform, which they termed a “Model T moment” for the company.

“The government is pulling back on incentives, such as the electric vehicle tax credit, but original equipment manufacturers are significantly invested and concentrated on the technology and affordability of EVs,” Keoleian noted, who also serves as a co-director of the U-M Center for Sustainable Systems, or CSS. “EVs are becoming the prevailing powertrain in other parts of the globe, and manufacturers are aware that is the future for the U.S.”

The research team at U-M comprised CSS/SEAS research specialists Christian Hitt and Timothy Wallington, along with postdoctoral fellow Maxwell Woody and Alan Taub, a professor in materials science and engineering. Taub also directs the U-M Electric Vehicle Center. Hyung Chul Kim, a research scientist at Ford, collaborated on the project, and Elizabeth Smith is the lead author, who contributed as a master’s student at U-M before finishing in May.

A high trim level lifecycle evaluation

In their “cradle-to-grave” evaluation, Keoleian and associates examined emissions figures not only from operating vehicles but also from producing and disposing of them. In this process, they considered various factors: powertrains, vehicle categories, driving behavior, and geographic location.

The powertrains comprised conventional internal combustion engines, hybrid electric, plug-in hybrids, and fully electric or battery electric options.

“““html

Vehicles utilizing these powertrains are denoted as ICEV, HEV, PHEV, and BEV, respectively. For the classification of vehicles, they examined pickups, sedans, and sport utility vehicles (considering “generic” versions of these models manufactured in 2025, which reflect new vehicles available in the market).

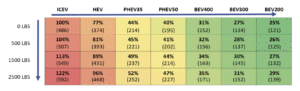

Driving patterns encompassed familiar elements such as highway versus urban operation, but also included contemporary considerations, like the vehicle’s location and the frequency with which PHEV drivers operated on battery power instead of gasoline.

Location influences emissions in two distinct manners, Keoleian noted. Initially, all vehicles—especially BEVs and PHEVs—consume more fuel in colder temperatures and experience reduced range in regions with lower temperatures. Subsequently, power grid emissions differ by region, making it more environmentally friendly to charge EVs in areas with a cleaner grid.

By addressing all these factors within a single study, the researchers were able to compare emissions from various vehicles in a straightforward manner. This allows for a comprehensive comparison of, for instance, a gasoline-powered pickup in Perry County, Pennsylvania, with a fully electric compact sedan in San Juan County, New Mexico.

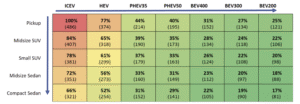

Alongside these intricate analyses, the research provided significant overarching insights. The study revealed for the first time that BEVs exhibit lower emissions throughout their lifespan compared to any other vehicle type in every county across the contiguous U.S. On average, ICE pickup trucks were the most significant emitters at 486 grams of carbon dioxide equivalent—a unit for measuring greenhouse gas emissions—per mile. Transitioning to a hybrid pickup could decrease that by 23%, whereas a fully electric pickup could lead to a 75% reduction.

Another striking statistic emerged from the team’s examination of how emissions fluctuated while a pickup was towing weight. A BEV pickup truck transporting 2,500 pounds still emitted less than 30% compared to an ICE pickup with no load.

In general, compact sedan EVs recorded the lowest emissions at merely 81 grams of carbon dioxide equivalent per mile—less than 20% of the emissions per mile of a gas-powered pickup. The least emitting vehicle category was the compact sedan BEV with the shortest range, 200 miles. The emissions linked to manufacturing batteries for vehicles with extended ranges increased their lifetime greenhouse gas contributions.

This also emphasizes another crucial insight from the study, Keoleian stated. Beyond electrifying your vehicle, selecting the smallest car that meets your needs will further curtail emissions.

“The key is effectively aligning your vehicle choice with your requirements,” Keoleian remarked. “Certainly, if you’re in a field profession, you might require a pickup truck. However, you can opt for a battery electric pickup. If your commute is just to work solo, I would suggest a sedan BEV instead.”

With the team’s online calculator, individuals interested in vehicle emissions can receive customized answers tailored to their circumstances. The research study is freely accessible and available to read.

“`