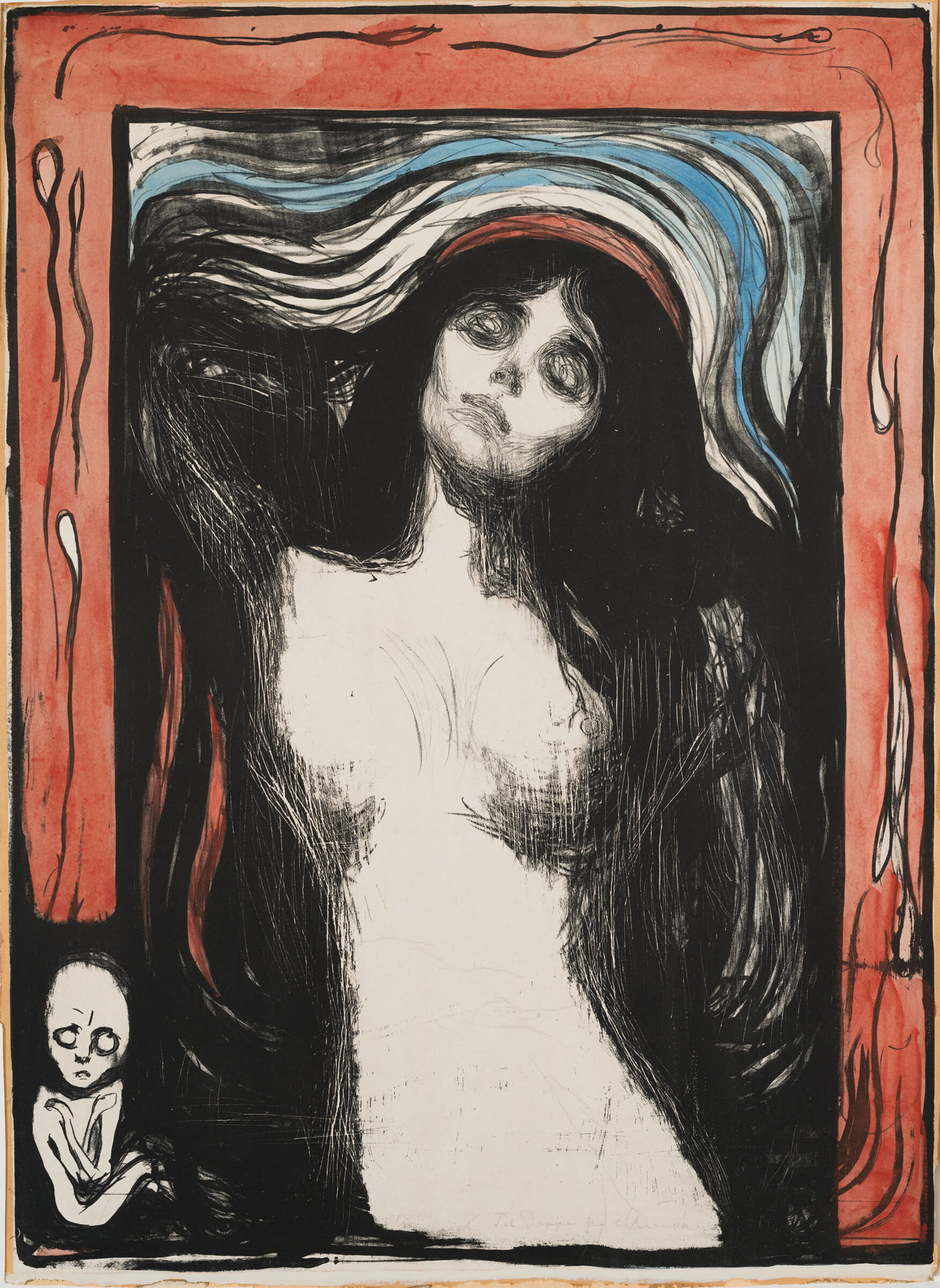

Edvard Munch, “Madonna,” (1895–1902).

Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, The Philip and Lynn Straus Collection, 2023.566. Photo: © President and Fellows of Harvard College; courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums

Edvard Munch’s prints and paintings entrusted to Harvard Art Museums

Exhibits scheduled for March will showcase the artist’s innovative printmaking and painting methods

A remarkable donation of 62 prints and two paintings by Edvard Munch, alongside a print by Jasper Johns, from the collection of Philip A. ’37 and Lynn G. Straus was revealed by Harvard Art Museums on Tuesday.

The spring 2025 exhibition, “Edvard Munch: Technically Speaking,” will highlight many of the newly donated pieces.

This legacy is a final act of kindness from the Strauses, whose affiliation with the museums began in the 1980s and includes various donations of artworks throughout the years; their role in a 1990s expansion, renovation, and endowment of the museums’ conservation center; as well as the funding of particular conservation and curatorial positions.

The contributions from Norwegian artist Edvard Munch (1863–1944) in the Strauses’ bequest add to a significant collection of Munch paintings and prints that are already held at Harvard, augmenting prior donations and facilitated purchases of Munch’s work by the couple— totaling 117 artworks. The cumulative total of pieces by the artist in the Harvard Art Museums’ collections now stands at 142 (eight paintings and 134 prints), representing one of the most extensive and noteworthy collections of Munch’s works in the U.S.

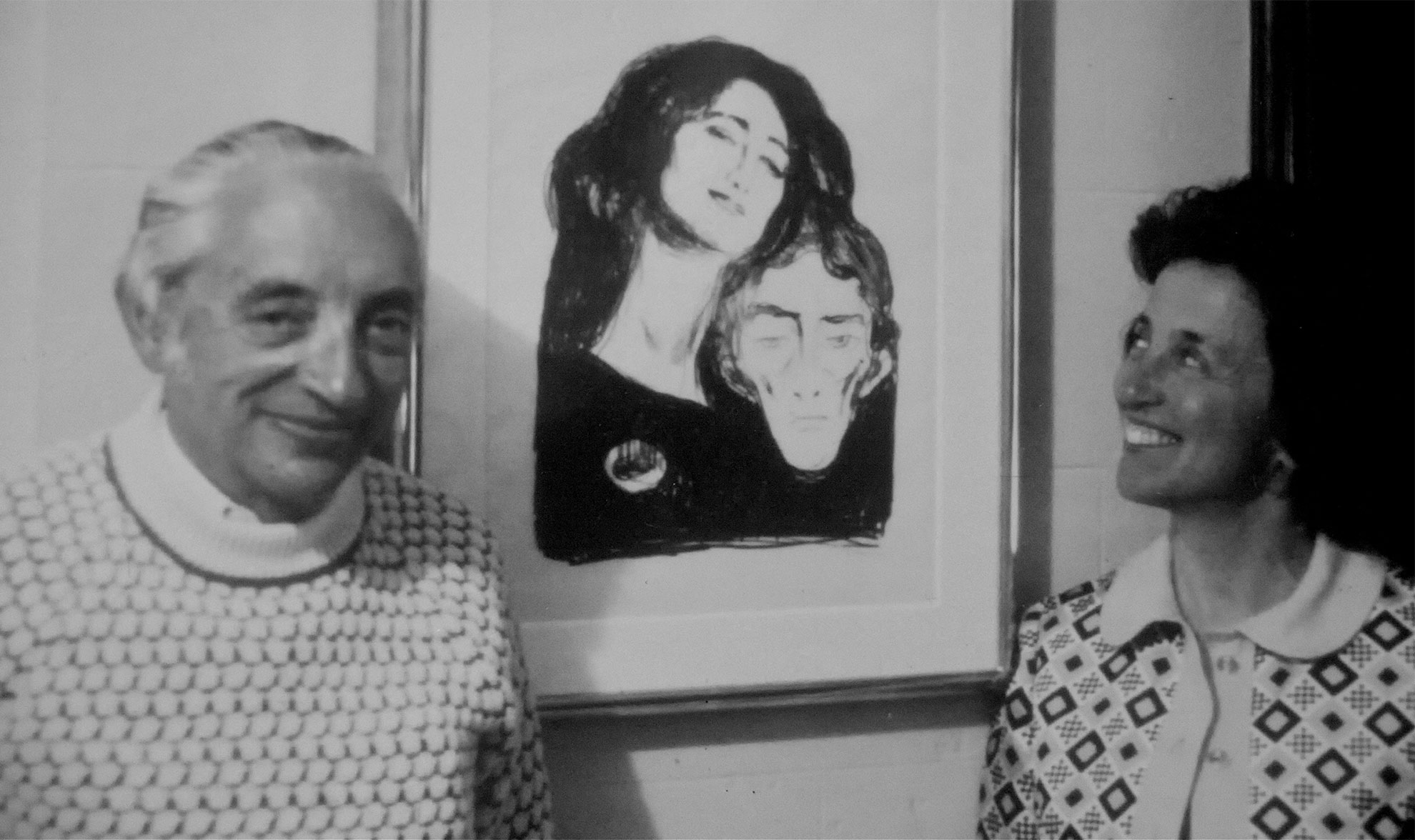

The Strauses have been recognized as among the most generous supporters of Harvard Art Museums. In 1969, they acquired their initial print by Munch, “Salome” (1903), which sparked their enthusiasm for the artist’s oeuvre. Following a commitment to a $7.5 million endowment in 1994, the museums’ conservation center—the oldest fine arts conservation treatment, research, and training facility in the U.S.—was rebranded as the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies. Philip, a portfolio manager and investment advisor from New York, passed away in 2004, and their bequest was realized at Harvard subsequent to Lynn’s death in 2023. Over their lives, the couple donated or facilitated the acquisition of 128 works for the Harvard Art Museums, including pieces by Max Beckmann, Georges Braque, Alexander Calder, Timothy David Mayhew, and Emil Nolde.

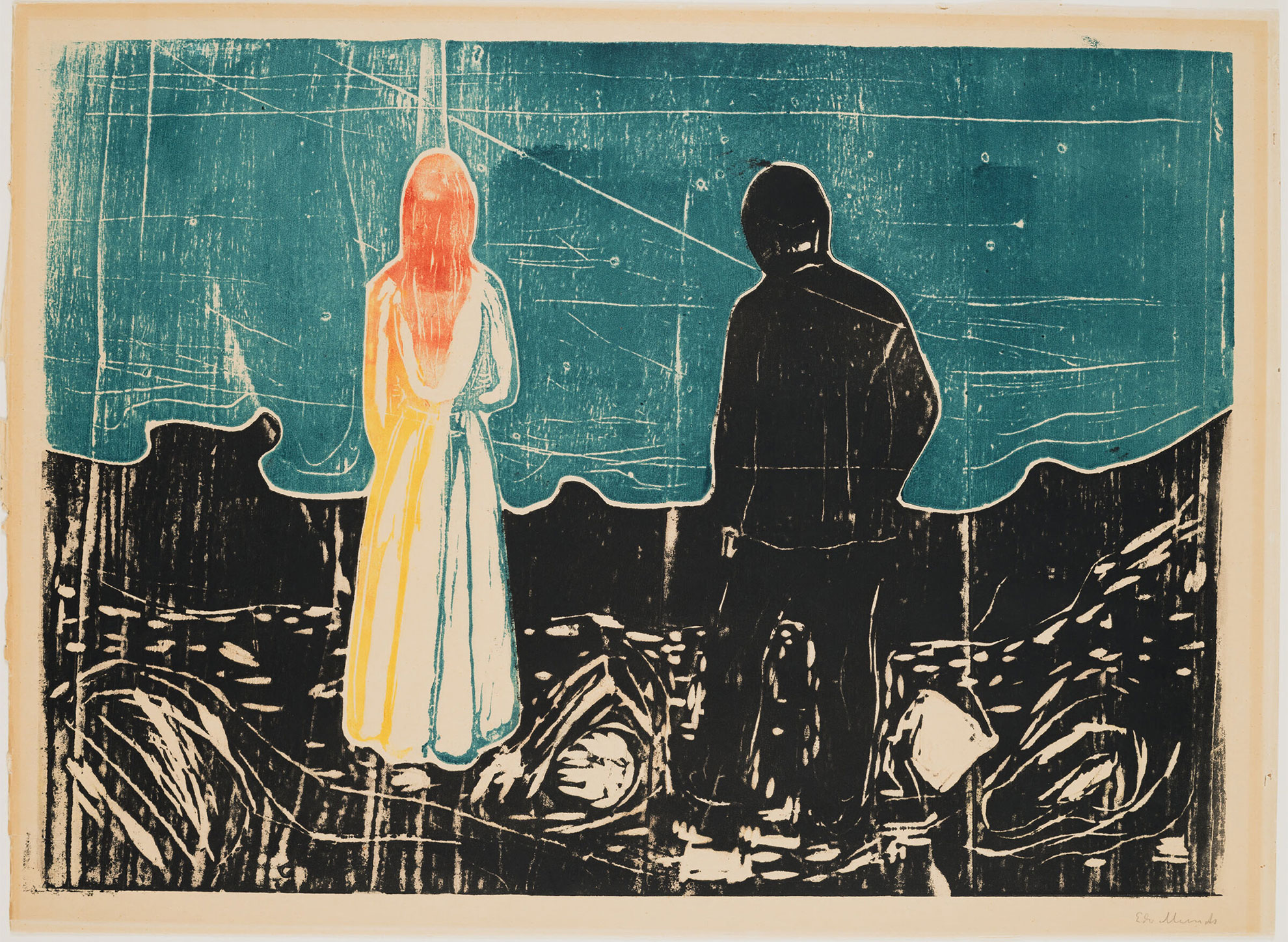

Edvard Munch, “Two Human Beings (The Lonely Ones),” (1906–8). Oil on canvas.

Busch-Reisinger Museum, The Philip and Lynn Straus Collection, 2023.551.

“Two Human Beings (The Lonely Ones)” (1899). Woodcut printed on tan wove paper.

Fogg Museum, The Philip and Lynn Straus Collection, 2023.602.

“Train Smoke” (1910) presents a landscape distinct from those by Munch previously in the collection.

Harvard Art Museums/Busch-Reisinger Museum, The Philip and Lynn Straus Collection, 2023.552. Photo: © President and Fellows of Harvard College; courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums

Unique instances of prints that Munch produced himself using his small hand-crank press, such as “Melancholy II” (1898).

Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, The Philip and Lynn Straus Collection, 2023.592. Photo: © President and Fellows of Harvard College; courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums

“We are profoundly thankful to Philip and Lynn Straus for their kindness and guidance throughout these years,” stated Sarah Ganz Blythe, the Elizabeth and John

Moors Cabot, the Director of the Harvard Art Museums, remarked, “Their passion for Edvard Munch’s work guarantees that future generations of students and visitors can engage with and study his prints and artworks right here in Cambridge. By adopting a unique approach to collecting Munch’s prints—actively pursuing and acquiring multiple representations of the same theme—they have assembled a collection that provides profound insights into the artist’s craft, making it ideally suited for a university museum with a robust teaching and research focus.”

Ganz Blythe added, “Their backing of the conservators and conservation scientists at the Straus Center has created a transformative effect on the many fellows who have trained there, as well as establishing a space where every object in our collections can be properly cared for and scientifically examined.”

The recent legacy left by the Strauses encompasses Munch’s renowned painting “Two Human Beings (The Lonely Ones)” (1906–8) and “Train Smoke” (1910), both of which now belong to the Busch-Reisinger Museum, one of the three constituent museums of the Harvard Art Museums. These artworks join “Winter in Kragerø” (1915) and “Inger in a Red Dress” (1896), which were previously presented to the museum by Lynn in memory of Philip in 2012.

Philip and Lynn Straus with their first Edvard Munch print, “Salome” (1903), circa 1969.

Courtesy Philip A. Straus Jr.

In “Two Human Beings (The Lonely Ones),” a man and woman stand shoulder to shoulder but feel estranged from one another, gazing toward the sea and away from the viewer, each set against a vividly layered landscape. Munch first portrayed this theme around 1892 and returned to it repeatedly in both his printmaking and painting thereafter. “Train Smoke,” which illustrates nature disrupted yet vibrantly invigorated by the Industrial Revolution, presents a landscape distinct from those already held in the collection. Both artworks showcase Munch’s exploration of color and surface texture, using a mix of thick impasto, diluted paint drips, and even sections of exposed canvas — a hallmark of Munch’s artistic heritage.

“The importance of Munch’s painting ‘Two Human Beings (The Lonely Ones)’ is difficult to overstate. It encapsulates the tension between closeness and solitude — both spatially and emotionally — addressing the universal theme of the human experience,” said Lynette Roth, the Daimler Curator of the Busch-Reisinger Museum at the Harvard Art Museums. “The Strauses had generously lent their painting for the original installation of the renovated Harvard Art Museums building that debuted in November 2014, and we are excited to be able to teach with and exhibit it alongside the other significant works from their collection in the future.”

Throughout 2024, both paintings underwent cleaning and other restorative processes by Kate Smith, senior conservator of paintings and head of the Paintings Lab, with the assistance of Ellen Davis, associate paintings conservator, both at the museums’ Straus Center. “Two Human Beings (The Lonely Ones)” had been varnished at some point in its past, which deviates from Munch’s practice of leaving his canvases without a consistent glossy finish. “Train Smoke” required paint stabilization and cleaning to eliminate atmospheric dirt. Following meticulous examination, the removal of varnish and grime from the paint surface, and treatment of minor paint losses, the paintings now reflect a closer resemblance to their original state.

The collection of 62 prints included in the Strauses’ recent bequest has been integrated into the Fogg Museum’s holdings. The majority are treasured impressions that Munch showcased during his lifetime, reflecting the aesthetic he preferred for displaying his prints: Some impressions are trimmed to the image and mounted on larger, sturdy brown paper, which Munch often signed and dated. Additionally, this collection consists of multiple states of individual compositions. They highlight the variety of techniques the artist employed in his printmaking: drypoint, etching, lithography, mezzotint, and woodcut, and innovations through the incorporation of hand-applied color such as watercolor, crayon, and oil, or printing with woodblocks cut into fragments.

“With this bequest, the Harvard Art Museums have positioned themselves as a pivotal site for the study of Munch’s prints,” stated Elizabeth M. Rudy, the Carl A. Weyerhaeuser Curator of Prints at the Harvard Art Museums. “There are countless opportunities this collection provides for teaching, exhibitions, and further research. Notable for its groups of versions, states, and variations of single compositions, this collection offers extensive insights into Munch’s inventive practice as a printmaker.”

Included in the bequest is the Jasper Johns print, “Savarin” (1982), a lithograph and monotype; it portrays a Savarin-brand coffee can filled with paintbrushes of varying sizes. The background features the artist’s distinctive “crosshatch” pattern from the 1970s, seen in other Johns prints within the museums’ collections. The arm depicted at the bottom of the print references the skeletal arm illustrated in Munch’s “Self-Portrait” from 1895 — a connection the couple recognized by displaying the two prints in close proximity within their home.

Visitors are invited to view the prints and paintings, by appointment, at the Harvard Art Museums’ Art Study Center. The special exhibition “Edvard Munch: Technically Speaking,” taking place from March 7 to July 27 at the Harvard Art Museums, will feature many works from the Strauses’ recent bequest alongside previous gifts. The exhibition will include approximately 70 pieces, enriched by key loans from the Munchmuseet in Oslo, Norway, and will showcase examples of the artist’s materials used in printmaking.