Quina technology was uncovered in Europe years ago but has not previously been discovered in East Asia.Ben Marwick

Although the Middle Paleolithic era is perceived as a vibrant period in European and African history, it often appears as a stagnant era in East Asia. New studies from the University of Washington confront that notion.

Scholars found a complete Quina technological system — a technique for crafting a series of tools — at the Longtan site in southwest China, which has been dated to approximately 50,000 to 60,000 years ago. Quina technology was revealed in Europe years back but has never been identified in East Asia until now.

The research team shared its results on March 31 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“This significantly alters our understanding of that region during that time frame,” stated Ben Marwick, co-author and UW professor of archaeology. “It provokes the inquiry of what other activities might have been occurring during this time that we have yet to uncover? How will this modify our views on people and human evolution in this region?”

The Middle Paleolithic, or Middle Stone Age, transpired around 300,000 to 40,000 years ago and is regarded as a pivotal phase in human evolution. This period is tied to the emergence and development of modern humans in Africa. In Eurasia, it relates to the advancement of several archaic human species like Neanderthals and Denisovans. Nevertheless, there is a prevalent perception that progress in China during most of the Paleolithic was slow.

The Quina system identified in China has been dated to 55,000 years ago, aligning with the timing of discoveries in Europe. This contradicts the notion that the Middle Paleolithic was inactive in the region and enhances our comprehension of Homo sapiens, Denisovans, and potentially other hominins.

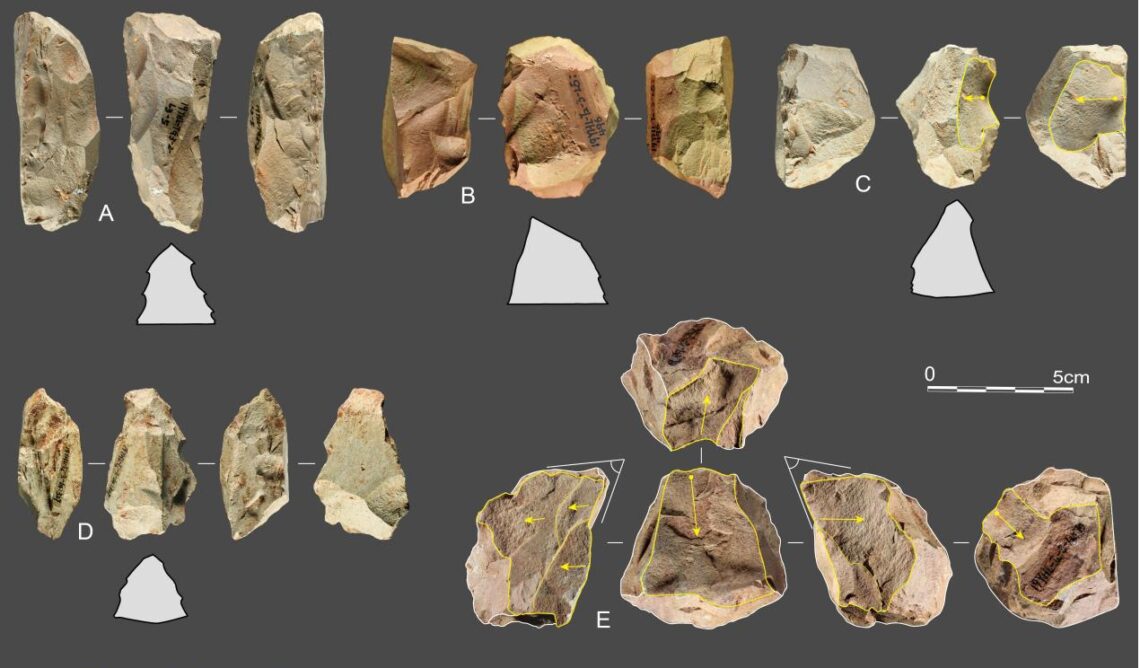

The most notable feature of the Quina system is the scraper — a stone instrument that is generally thick and asymmetrical with a wide and sharp working edge showing evident signs of use and resharpening. Researchers uncovered numerous examples of these, along with the remnants of their fabrication. Minute scratches and chips on the tools reveal they were utilized for scraping and scratching bones, antlers, or wood.

Marwick noted that the central question now is: how did this toolkit reach East Asia? Scholars will investigate whether there is a direct link — with individuals migrating gradually from west to east — or if the technology was independently developed without any direct interactions between groups.

Finding an archaeological site with a well-defined set of layers would be advantageous, Marwick mentioned, allowing researchers to identify what tools were created prior to the emergence of Quina technology.

“We can assess whether they were experimenting with something similar beforehand, from which Quina evolved,” Marwick remarked. “If that’s the case, development could appear more local — they were trying out different forms in prior generations and finally refined it. Conversely, if Quina emerges without any visible signs of experimentation, it would suggest that it was passed on from another group.”

There are probably various reasons why Quina technology has only recently been discovered in East Asia. One aspect, Marwick explained, is that archaeologists working in China are becoming more familiar with archaeological practices in other regions of the planet and how to recognize their findings. He also indicated that the pace of research is accelerating, increasing the likelihood of uncovering rare artifacts.

“The belief that nothing has changed for an extended period in East Asia also strongly influences people’s perspectives,” Marwick stated. “They haven’t seriously considered the potential of discovering items that contradict that notion. Now, there might be some scholars who are eager to challenge those ideas.”

A considerable amount of archaeological discovery hinges on chance, Marwick asserted, but a key goal moving forward is to uncover human remains in the region.

“That could clarify whether these implements were created by a modern human like you and me,” Marwick stated. “No Neanderthals have ever been discovered in East Asia, but is it possible we might uncover a Neanderthal? Or, more likely, could we find a Denisovan, which represents another category of human ancestor? If we manage to locate human remains associated with this time frame, something surprising could emerge — perhaps even a new human ancestor that has yet to be identified.”

Other co-authors of this study were Qi-Jun Ruan, Hao L, Pei-Yuan Xiao, Ke-Liang Zhao, Zhen-Xiu Jia, and Fa-Hu Chen from the Chinese Academy of Sciences; Bo Li from the University of Wollongong in Australia; Hélène Monod from the Universitat Rovira i Virgili in Spain; Alexander Sumner from DePaul University; Jian-Hui Liu at the Yunnan Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology; Chun-Xin Wang and An-Chuan Fan from the University of Science and Technology of China; Marie-Hélène Moncel from the National Museum of Natural History in Paris; Marco Peresani and Davide Delpiano from the University of Ferrara in Italy; and You-Ping Wang from Peking University in Beijing.

This research was sponsored by the National Natural Sciences Foundation of China, the Open Research Fund of TPESER, the National Natural Science Foundation of China again, the Australian Research Council, and the University of Ferrara.

For further details, contact Marwick at [email protected].