Country & Globe

Released JFK documents offer ‘greater insight’ on CIA activities, historian asserts

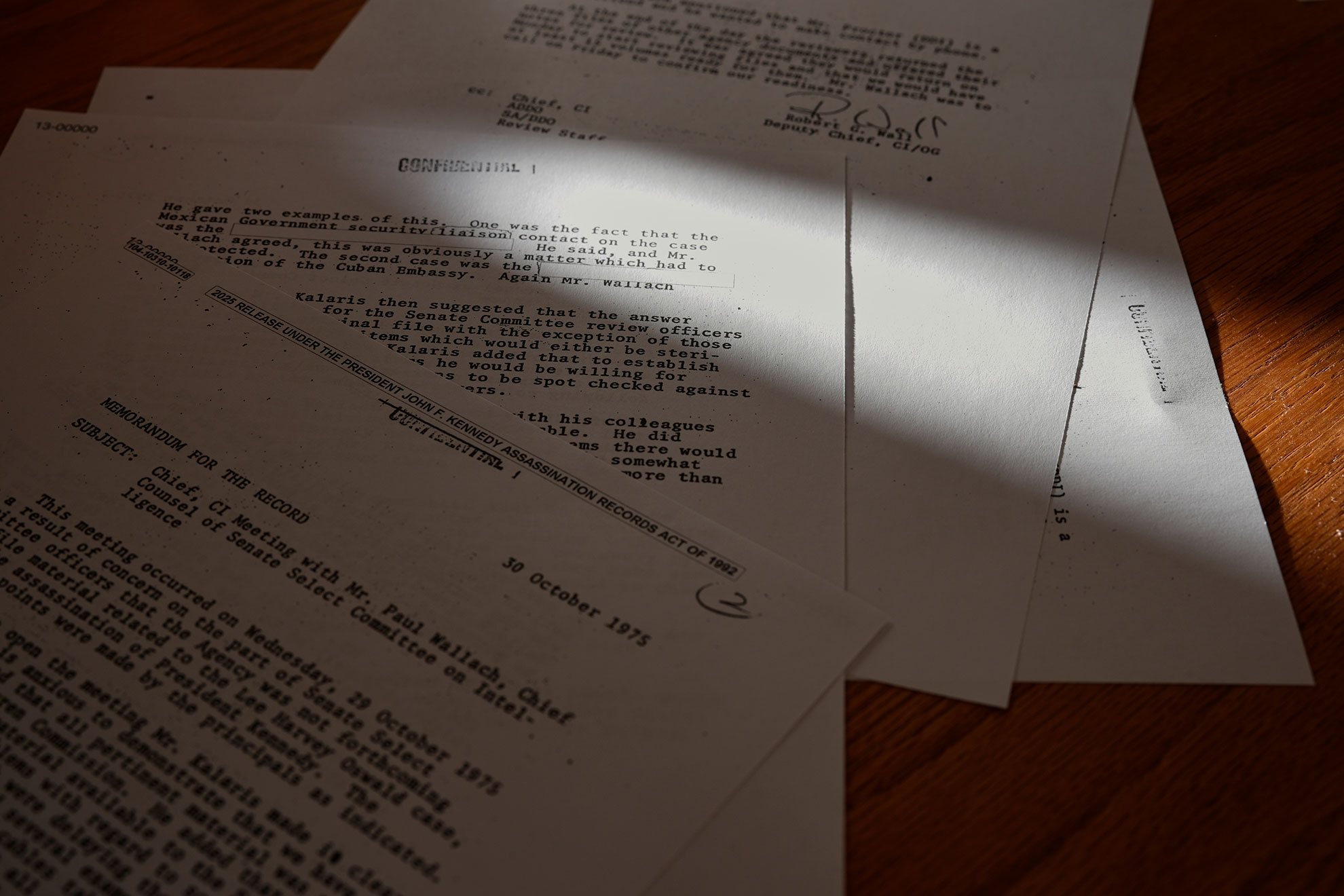

Documents related to the assassination of President John F. Kennedy were made public on March 18.

George Walker IV/AP Photo

Fredrik Logevall, Pulitzer Prize recipient authoring a three-part Kennedy biography, on what surprised him and what information he still seeks

Sixty years later, Americans have gained more insight into the CIA’s underhanded operations during the early 1960s, notably in Cuba and Mexico, due to a recent batch of declassified materials regarding the assassination of President John F. Kennedy made public last week.

So far, over 77,000 documents unveiled by the National Archives and Records Administration have not contradicted the Warren Commission’s finding that assassin Lee Harvey Oswald acted independently when he shot Kennedy in Dallas on November 22, 1963. However, historians indicate there are significant new insights concerning the CIA’s participation in foreign elections during the Cold War and its infiltration of Fidel Castro’s close associates.

In this edited discussion with the Gazette, Fredrik Logevall, a history professor and the Kennedy School’s Laurence D. Belfer Professor of International Affairs, outlines his expectations from the documents and what he has discovered thus far. An author honored with a Pulitzer Prize, Logevall published the initial volume in a three-part series on Kennedy’s biography in 2020. The succeeding book is set for release next year.

What are your thoughts on this new set of JFK records? Have you encountered anything noteworthy yet?

In relation to the assassination, there’s very little that’s new, at least based on my observations up to this point. I can’t claim to be shocked — I didn’t anticipate that we would uncover anything that would disrupt our understanding of the events in Dallas. Nonetheless, the releases present fascinating insights on U.S. covert operations during the Cold War of the early 1960s. Some extend beyond Kennedy’s era, but they are most intriguing for this period, particularly regarding Latin America. This has proven quite enlightening for me.

“Interesting” with regard to the CIA’s actions or the extent of their activities back then?

In some respects, it encompasses both. Many of the “new” documents had been previously released; the distinction now lies in the fact that they are unredacted. For instance, in 2017, we received significant CIA documents, but they contained various words or sections obscured. What has been enlightening for me, even if it’s just a few words, is witnessing those terms restored. This is significant because, as we recognize, even a handful of words can dramatically alter the interpretation of a sentence or section. What we observe with greater insight is the considerable involvement of the United States in foreign nations, particularly regarding election interference. Previously, country names or leaders’ identities would have been omitted. Now they appear plainly for all to see. There’s something starkly clearer about seeing terms like “Brazil” or “the Finnish elections.” Moreover, it illustrates the substantial presence of the CIA. In specific embassies, CIA personnel could account for nearly half of the total staff. Even for us historians of the Cold War, these statistics are somewhat startling. A week ago, I would have estimated that at most 20 percent in key embassies would be secretly affiliated with the CIA. I had no clue that in some cases, it was nearing 40 or even 50 percent.

Fredrik Logevall.

Photo by Peter Hessler

Have we uncovered more understanding regarding Kennedy’s complicated relationship with the CIA?

We haven’t, though it’s possible that pertinent information lies buried within the documents, and I have not yet encountered it. I expected we might gather more insights about that crucial relationship. You are correct to state there was a cautiousness between JFK and the agency for various reasons. Some writers have overstated the depth and breadth of the divide, but it definitely existed.

What’s something significant you’ve discovered?

In a CIA document dated April 24, 1963, it is revealed that 14 Cuban diplomats were acting as our agents. That’s quite remarkable — highlighting the extent to which individuals within the Cuban government were actually collaborating with the agency. In terms of the so-called Operation Mongoose, aimed at destabilizing and overthrowing the Cuban regime, this offers a clearer understanding of how Cubans were aiding that initiative. Later within the same document, we learn that two Cuban ambassadors were on the payroll, providing exceptional reports and closely attuned to Castro’s thoughts.

What are some essential inquiries historians still hold regarding the Kennedy assassination? Is there much more to uncover?

I would like further insight into Oswald’s movements before Dallas. I am eager to learn more about his trip to Mexico City, occurring in late September to early October 1963, shortly before the assassination. He was contemplating defection to Cuba and met with Cuban as well as Soviet diplomats while in Mexico City. What exactly transpired in those discussions? I am interested, more broadly, in what U.S. intelligence agencies were aware of or unaware of regarding his whereabouts during that time frame. That remains perhaps the most significant issue for me.

The JFK assassination is frequently referenced as the catalyst for modern conspiracy theory culture. Why is there such enduring suspicion surrounding it?

Partially, it’s due to the fact that a president was assassinated, seemingly in the prime of life. We humans possess a natural tendency to assume that monumental events must stem from substantial causes. It appears somehow implausible that a solitary misfit named Lee Oswald took it upon himself to execute the president. We convince ourselves that there must be more to the narrative. Consequently, conspiracies will persist. Despite what these documents may or may not have revealed, it would not quell the skepticism of those who believe there were additional parties involved.

Someone inquired why we don’t appear to share the same intense interest in, say, Lincoln’s or RFK’s assassination. This could be attributable to several factors. Firstly, Oswald was killed two days later. Naturally, this leads individuals to ask, “How was that permitted to occur?” Secondly, the Warren Commission, established by the government to investigate the murder, conducted a serious and diligent inquiry but made errors, notably in failing to interview everyone they could have. Lastly, the fact that the assassination was documented on film could contribute to the ongoing intrigue. Many individuals have viewed the Zapruder film, and it lingers in our consciousness, making the event more tangible and everlasting. Additionally, there’s a commonly expressed notion — the implications of which I’m still trying to decipher myself — that something significant was lost during that day in Dallas; that it somehow marked the end of American innocence.

Considering all these aspects, perhaps they provide part of the rationale as to why this specific event has been such a subject for conspiracy theories.