The Trump administration has positioned federal agencies and federal personnel at the forefront of national discussions. For historian Peter Kastor, this prompts a series of inquiries. How did that federal workforce emerge? What type of government did the Founding Fathers assert they desired? And what kind of government did they genuinely establish?

Kastor, the Samuel K. Eddy Endowed Professor in history within Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis, has dedicated years to the collection and digitization of records for 37,000 individuals who served in the federal government from 1789 to 1829. The findings are now accessible for public viewing through the “Creating a Federal Government” digital archive.

In this Q&A, Kastor elaborates on the project, the priorities of the early federal workforce, and the essence of the confirmation procedure.

What inspired the inception of this project?

Like every historian, I aimed to narrate a story that had not been shared before. However, there’s another backstory as well.

My initial job post-college was with the Justice Department, working in the division that enforces the Voting Rights Act. As we approached the 1990 census, I observed how journalists were highlighting the political and partisan aspects of redistricting. They were correct in many respects, but they overlooked the realities of governance — particularly the role played by offices like ours in reviewing and sometimes redefining electoral districts.

It became evident to me that an intriguing narrative existed regarding how government employees perform their roles. This encompasses not only their directives from superiors but also the limitations placed on leadership regarding their capacity to enforce those directives.

The timeless organizational dilemma …

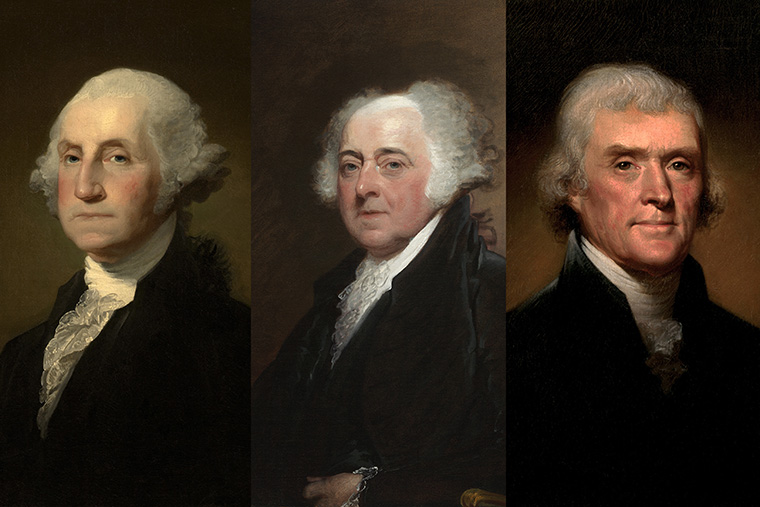

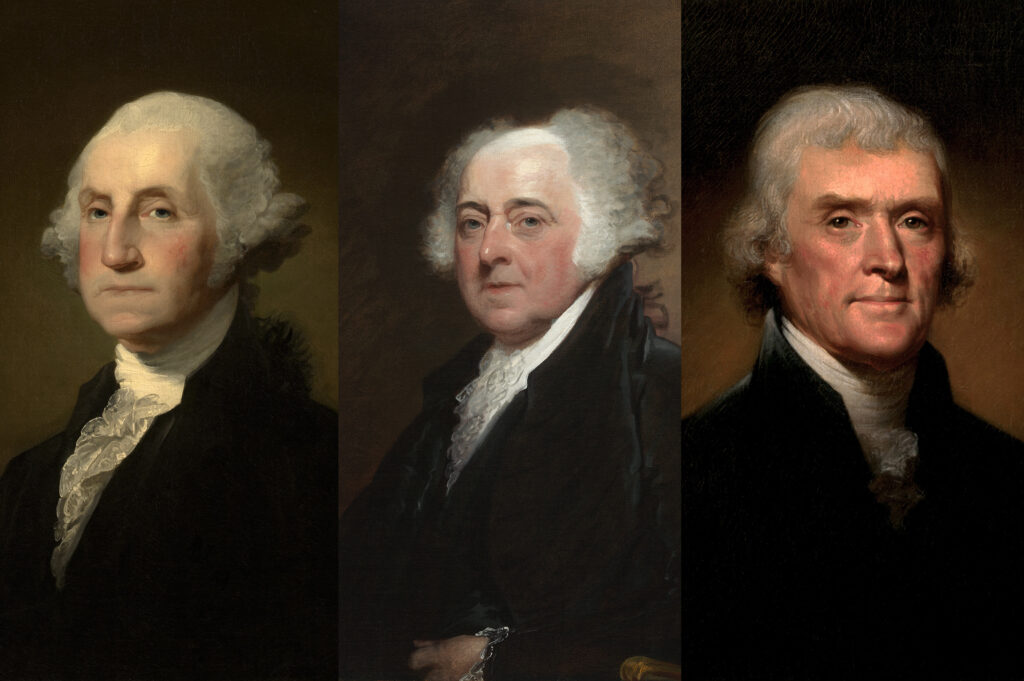

Certainly. I’ve examined notable figures such as Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, and George Washington. However, I discovered that much of the significant activity was undertaken by mid- and lower-level officials. They were tasked with executing the founders’ resolutions without any direct communication channels.

How did those officials react?

With trepidation and independence.

Customs officials impose tariffs on imported goods. This is critically significant for federal revenue but places them at the intersection of trade and international diplomacy. They tend to be a cautious group.

Many higher-ranking officials — U.S. attorneys, territorial governors — had prior experience in elected roles. They are accustomed to wielding power and find themselves more at ease in decision-making.

Was any of this information digitized beforehand?

A minor portion. The State Department keeps a digital directory of principal officers and heads of mission. During the period I analyze, this comprises a few hundred individuals. The Federal Judicial Center — whose main historian, Christine Lamberson (BA ’04), is an alumna of WashU — maintains an excellent database of federal judges, totaling another 140.

So who makes up the remaining individuals?

The largest group, numbering around 15,000, are postmasters. In the 1960s, the National Archives developed a preliminary catalog of postmasters — essentially a ledger with loose-leaf pages, much of the data handwritten. Furthermore, starting in 1816, a continuous resolution passed by Congress mandated the executive to compile, every two years, a list of all federal employees. This includes every customs official, territorial official, and commissioned officer in the U.S. military. These were invaluable sources, yet their contents had never been comprehensively digitized.

You enlisted numerous students. How labor-intensive was the process of digitization and transcription?

Highly laborious. This involved a combination of typewritten and handwritten documents. Optical character recognition software could not yield reliable outcomes.

An additional challenge was distinguishing between similar entries. I’ve examined William Clark, recognized primarily through the Lewis and Clark expedition. However, there are countless other William Clarks, and they appear in very unique manners. Spellings of names vary, and nominations are described differently. We couldn’t rely on a computer to resolve all those discrepancies.

The geospatial aspect posed similar difficulties. Occasionally mapping was straightforward. However, if we examine an appointee from St. Louis, existing software would place the dot for St. Louis at the geographic center of the city’s present boundaries — near the east edge of Forest Park. In 1804, that land was not even farmland; it was the outskirts of Osage territory. Thus, we needed to identify the historical location of the city, which aligned with the current site of the Gateway Arch. We repeated this process for more than a thousand cities, towns, neighborhoods, and even individual buildings.

Clark appears on the homepage, along with John Quincy Adams, Elizabeth Kelly, and Thomas Melville. What is the significance of these four individuals?

I sought individuals who would exemplify the diversity of experiences within the federal workforce.

Clark is notable. He served as the territorial governor of Missouri, a significant position but not one within the cabinet. Federal service constituted a critical part of his identity as an American, yet he definitely viewed himself as subordinate.

Adams is a well-known figure. He is recognized as one president and the son of another. However, he also dedicated several decades to diplomacy. He stands out as a prime example of individuals who served the federal government outside the United States, along with the small group who reached high political office.

Kelly was a nurse at a marine hospital in the 1820s. We lack information about her birthplace or death. Nonetheless, she represents one of approximately 100 women in this collection. The majority are postmasters, with others serving as nurses or, intriguingly, as lighthouse keepers. She serves as a reminder that women have contributed to the federal government from its inception, but it also underscores the stark limitations on their opportunities. Additionally, I wanted…to incorporate her since I was unaware of her birth date or the year of her passing. She serves as an excellent illustration of the boundaries of our knowledge.

Melville served as a revenue officer in Massachusetts. The Revenue Act of 1789 transitioned many state roles into the federal framework. Melville had participated in the Revolution and, utilizing that experience, corresponded directly with George Washington. Four decades later, he remains in his position. It was a stable job. Subsequently, when his grandson, Herman, attempts to establish himself as a writer, he secures a daytime position at the New York customs house. He represents a fine example of the long-serving, mid-level officials who were among the initial federal employees.

What insights does this archive provide about the essence of the early federal government?

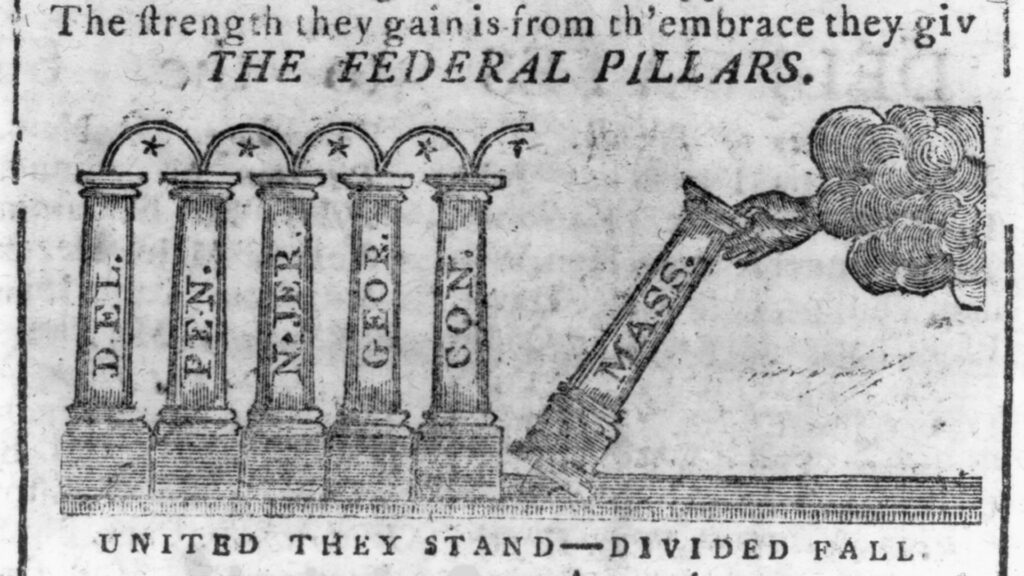

The archive illustrates how Americans interacted with their government on a daily basis. Specific offices were ubiquitous. Postmasters transported mail between states. Federal judges resolved interstate disputes. They demonstrated that the union was genuine. They embodied the belief that, as Americans, we are all interconnected.

Once we move beyond that, most federal officials along the Eastern Seaboard engaged in revenue collection. Their role was to generate funds. A significant portion of that revenue was allocated to the West. It was used to broaden freedom while also restricting it; to advocate for equality while simultaneously suppressing it.

In what way?

The greatest domestic challenge for the federal government was transforming the western territory into federal areas and subsequently into states. This endeavor is quite expensive. It requires a substantial workforce. Moreover, it is based on the idea that individuals residing there will become equal citizens.

Nonetheless, the federal government also remained deeply committed to maintaining slavery. Additionally, the majority of the U.S. Army is stationed in the West. Part of this is due to worries regarding the Spanish Empire, but it primarily revolves around policies towards Native Americans.

Your dataset comprises 5,000 presidential nominees. What insights did you gain about the confirmation procedure?

Let’s begin with how individuals sought nominations, as we possess over 18,000 letters of application and recommendation for office. What struck me was that applicants framed their requests more in terms of national allegiance than party affiliation. They commonly expressed support for the Constitution. They endorsed executive authority. They backed the autonomy of the other branches.

When the time came to decide how best to appoint individuals to office, George Washington set the precedent, and his successors accepted it without question. Legislation required him to present some positions to the Senate for their advice and consent. In actuality, he submitted many more. At one instance, he even entered the Senate chamber physically. When he arrived, the senators inquired about his purpose. Washington responded that he had come to seek their counsel and consent regarding a series of nominations. Senators expressed skepticism, arguing that although Washington claimed to desire their advice, they perceived he was insisting on their consent.

For the senators, Washington’s presence in the Senate was seen as an encroachment of the executive branch on the legislature. He never repeated that tactic. The senatorial concern was understandable, although they may have overreacted. Washington held a strong belief in the separation of powers and the system of checks and balances regarding advice and consent.

Thus, senatorial confirmation wasn’t merely a bureaucratic obstacle?

Absolutely not. They never perceived it that way. The early Senate approved nominations at a rate of 90%. However, similar to the earliest presidents, they believed that the process embodied the concept of checks and balances. They felt this quite strongly.

In numerous respects, this government was exceedingly inefficient. When the secretary of the treasury corresponded with individual customs collectors, it was inefficient. When the president handwrote nominations, that too was inefficient. Yet, they lacked alternative methods. Simply put, they didn’t possess HR managers. There was no bureaucratic framework.

However, I believe these narratives reshape our understanding of the founding period. The founders emerge as individuals who, yes, cared about lofty political theory, but equally focused on the management of governance.

The post Creating a federal government appeared first on The Source.