“`html

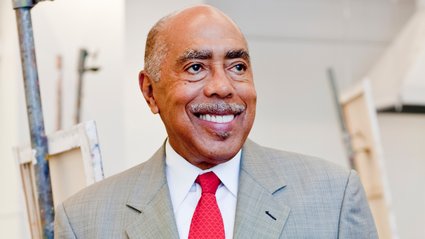

Dr. Walter Massey, president emeritus of Morehouse College and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, former director of the National Science Foundation, and past director of Argonne National Laboratory, will present the keynote address at Caltech’s 131st Commencement Ceremony on June 13, 2025.

In this context, he contemplates his extraordinary journey; the insights gained during his tenure as an educator, mentor, and academic leader; and strategies scientists can employ to convey the significance of their work to the general public.

Q: You have consistently assumed significant leadership positions. What principles have influenced your career as well as your decision-making when such chances emerged?

A: That has evolved as I’ve matured. Initially, I simply desired employment. During my first role at Argonne, I engaged in research. Then, I sought to be in environments I believed were premier, enabling me to learn from the finest talents. This was partially why I joined the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign in 1968. This was following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. I resided in Chicago at the time, and much of the west side was in turmoil. I lived in the same neighborhood currently, Hyde Park, and felt I wasn’t contributing to the civil rights movement. From that point on, my decision-making began to factor in how I could personally commit to initiatives that would benefit others, particularly the Black community. I became intrigued by roles aimed at increasing minority representation in science. As I ascended to senior leadership roles, my choices increasingly involved considering the impact of a position on society, be it in the scientific realm or in aiding individuals. This became a major aspect of my decision-making process.

Q: How did your passion for physics develop, and what was your journey to becoming a physicist?

A: I enjoyed mathematics during high school, yet I didn’t enroll in any science courses until I entered college. I started college in the 10th grade, and at that point, I had never taken a physics or chemistry course. In my initial physics class, I collaborated with a professor who became a mentor and friend: Sabinus Hobart Christensen. We referred to him as “Chris.” Since I hadn’t studied trigonometry, I struggled with vectors. Chris had to tutor me in trigonometry after class so that I could successfully take the course, and I received a C+. I was proud of that! Working with him ignited my fascination with physics as a means to apply mathematics to grasp the world around me. What I found appealing was the ability to become completely engrossed in solving intricate problems. Regarding Caltech, I thoroughly enjoyed staying up late working through Feynman diagrams.

I also aspired to be a jazz saxophonist. That’s what I initially hoped to pursue upon entering Morehouse. However, when I arrived at college, I discovered others who could improvise jazz far better than I could. I excelled in math compared to many of them, thus I pursued the path of physics.

Q: At Caltech, LIGO (the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory) stands out as a potent illustration of the value of long-term investments in high-risk ventures. You were the director of the National Science Foundation (NSF) when this proposal emerged and you played a role in persuading Congress to support it. How did you identify that this was a timely and crucial initiative?

A: It wasn’t solely my recognition. There was a team at the NSF that had been exploring it for years, including Kip Thorne at Caltech. I became deeply engaged because I saw it as an exciting possibility if it could be realized. It was worth our efforts to secure funding, as that was precisely the type of endeavor the NSF was designed to support. No other agency could have undertaken funding for it. I had colleagues—Bill Harris and others—who were just as passionate. Interacting with individuals like Barry Barish and others fueled my enthusiasm. Their vision for LIGO was so captivating and inspiring that I felt compelled to support it.

Q: You have dedicated a significant part of your career to creating opportunities for marginalized groups, enhancing inclusion, access, and equity. In your view, what are the most effective strategies to promote these values?

A: There are numerous obvious actions that must be taken. We haven’t yet reached a stage where we can confidently assert, “If we do this, we can guarantee the results.” However, we can declare, “If we do not take these actions, results will not materialize.” Early courses in math, science, and reading are crucial, as is early exposure to scientific fields. I value museums greatly. I am quite connected to the Griffin Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago—I’ve been a trustee for many years. They welcome youngsters to their exhibits. They offer classrooms and employ teachers who engage in hands-on activities to spark excitement in kids. I believe that aspect is vital.

As young individuals progress, we must maintain their engagement. We need to instill a sense of confidence that they can pursue science if they wish to. Over the years, especially in physics, this has been a significant challenge in introductory undergraduate courses. The dropout rates from first-year physics classes used to be alarming. Students would enter, eager to study physics, but often left the course feeling incapable due to insufficient support from faculty. We must develop a better methodology for helping students realize that they may not want to pursue a subject without allowing them to feel inadequate. Thus, they exit feeling less reinforced and less excited about the topic than they did upon entry. I believe many also become disheartened about science as a consequence.

Q: With proposed reductions to federal funding and shifting public views on the importance of higher education, what key messages regarding the value of higher education, science, and engineering should the research community communicate to the public?

A: We must remind the community of the advantages that science has already bestowed upon society and civilization. I believe people are aware of this, but we have reached a stage where, for some reason, they have not internalized it or cannot express it. Or they may even disagree, thinking, “All these benefits you’ve mentioned haven’t been evident in my experience. I’ve faced job loss due to technological progress. I perceive no health-related advancements improving my well-being. I am skeptical about climate change. Many claims of breakthroughs by scientists seem to have little benefit for me.” I believe we need to develop more strategies to counter such sentiments.

In this endeavor, I think it would be advantageous for the scientific community to exhibit more humility and less arrogance. One of the factors that have diminished public support is the perception that we scientists have become just another group lacking connection with them. “These individuals who are more knowledgeable than I look down on me. They lecture me on why my opinions are misplaced.” We must reconsider our communication style.

We must continuously remind people that scientists are human. They err. We haven’t emphasized this sufficiently. Many unsuccessful attempts precede every public announcement of results. Our approach has typically been to highlight breakthroughs without discussing the missteps encountered, the late nights, and the frustrations. The public is only aware of our successful outcomes. We need to find opportunities to showcase the human aspect of science more effectively.

Q: Without disclosing too much about your upcoming address on June 13, could you share some aspirations you hold for Caltech’s graduating class of 2025?

They are graduating at a pivotal moment in the history of American science and globally, during one of the most crucial times in American society. As Caltech graduates, they stand uniquely positioned at the intersection of these issues. When one states they are a Caltech graduate, society expects them to be exceptional, and they are. I hope they discover ways to remain engaged with the exhilaration that science presents and begin to recognize how their scientific endeavors can impact the world positively.

“`