“`html

Images by Niles Singer/Harvard Staff Photographer

Science & Technology

Contentions of pure lineages? Ancestral territories? DNA research asserts otherwise.

Geneticist elucidates how advancements in technology reveal a narrative of mixing, movement, and displacement in human history.

The history of humanity is filled with disputes regarding the purity (and superiority) of the lineages of one faction over another and claims surrounding ancestral regions.

A decade of research on ancient human DNA has drastically altered this narrative.

Rather, Harvard geneticist David Reich commented on Monday, increasingly refined inspection of genetic material enabled by technological progress demonstrates that nearly everyone originates from elsewhere, and everyone’s genetic heritage reveals a blend from various waves of migration traversing the globe.

“Ancient DNA can glimpse into the past and discern how individuals are connected to each other and to contemporary populations,” Reich articulated during a presentation at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study. “And what it reveals are worlds we had not previously envisioned. It’s profoundly astonishing.”

Human groups have undergone significant transitions for tens of thousands of years since our departure from Africa. Although the specifics of this evolving narrative are intricate, the overarching theme reflects an increasing homogenization since human diversity dwindled from the era when modern humans coexisted with Neanderthals, two types of Denisovans, and the diminutive Homo floresiensis of Indonesia.

Reich, a Harvard Medical School genetics professor, stated that human diversity is presently at its lowest point compared to any previous era.

“Today, we are very alike. Even the most diverse individuals are at most perhaps 200,000 years apart, with limited gene exchange,” Reich noted. “But 70,000 years ago, there were at least five groups significantly more distinct from each other than any present-day populations.”

These themes hold true even in the continent widely regarded as the origin of humanity.

In Africa, research has revealed that various tribal and linguistic groups have shifted over time, displacing others and intertwining genetically. For instance, Cameroon, a region associated with Bantu languages, was occupied by an entirely different population 3,000 to 8,000 years ago, Reich noted.

Reich’s own trajectory traces the development of the nascent science of employing ancient DNA analysis to gain insights into humanity’s past.

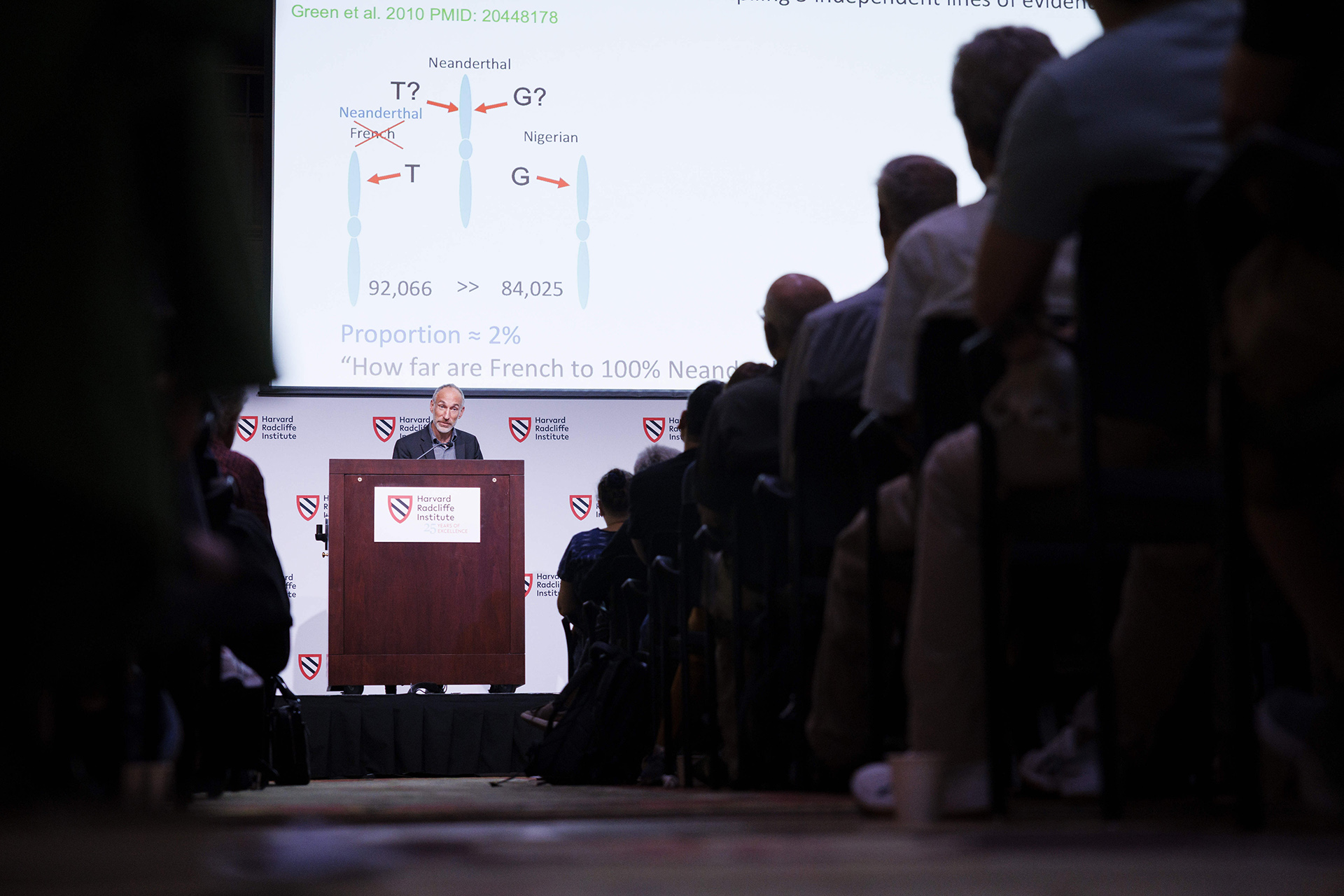

In 2007, Svante Pääbo declared he had extracted DNA from Neanderthal remains. At that time, Reich was an assistant professor focused on prostate cancer at HMS, and he immediately regarded the new findings as the most critical for understanding our identity and origins.

When Pääbo assembled an international team to analyze the findings and deepen the understanding of the Neanderthal-human connection, Reich joined in, dedicating the next seven years to data analysis that he dubbed his “second postdoc.”

“It’s just such remarkable, thrilling, like sacred data. It’s incredibly significant,” Reich expressed. “And I believe that sentiment was shared by all participants in our international collaborations.”

Prior to this research, geneticists had convinced themselves that humans and Neanderthals had never intermingled, but the analysis indicated otherwise.

Reich described his amazement as the results surfaced. The research team presumed the outcome was erroneous and continuously sought explanations to refute it.

Ultimately, however, they acknowledged the finding, uncovering that Neanderthals and modern humans interbred, with most contemporary Europeans possessing about 2 percent Neanderthal ancestry.

“People’s narratives regarding their lineage are nearly always incorrect. I don’t view that as negative. I believe it’s a positive and humbling realization.”

Since then, it has become evident that modern humans mated with another early human species, the Denisovans, whose remains were discovered in a cave in Siberia and are now thought to have inhabited a broad area across Asia.

Their genetic traces are most pronounced among populations in East Asia and the Pacific islands.

“It’s obvious that modern and primitive humans intermingled wherever they encountered one another,” Reich remarked. “It’s not uncommon for individuals to blend with those who are quite dissimilar. In fact, this is the norm.”

Additionally, human migration was considerable.

Neanderthal genes have been identified in East Asians, even though Neanderthals resided in Europe and West Asia. The dominant perspective prior to the emergence of ancient DNA analysis was that technology and language proliferated more due to cultural interactions than through actual migration.

Now, it appears as though groups of hunter-gatherers inhabited Europe before the arrival of farmers, who introduced agriculture alongside their genetic legacy.

Later, between 5,000 and 6,000 years ago, mobile pastoralists known as the Yamnaya emerged from the Asian steppe, leaving a substantial genetic footprint — 75 percent in Germany and 90 percent in Britain — potentially introducing the Indo-European language that evolved into various European languages.

In the Iberian Peninsula — present-day Spain and Portugal — the genetic impact of the Yamnaya is less pronounced than in Germany and Britain, approximately 40 percent, but the Y chromosome of the initial farmers that preceded them is completely nonexistent in the population, indicating that the transition “cannot have been a pleasant experience for the men involved,” Reich commented.

“The local male demographic entirely failed to pass along its Y-chromosomes to the ensuing population,” Reich noted. “The reasons behind this phenomenon remain a mystery, but several millennia later, the descendants of these Iberians migrated to the Americas, and a similar event occurred. Individuals in Colombia possess almost no local Y-chromosomes.

“““html

They are predominantly European. Yet, they possess almost no European mitochondrial DNAs (transmitted through the maternal lineage). They are primarily Native American, a consequence of exploitation and societal disparity. This might very well be what transpired here.”

“The significant shift in perspective from ancient DNA research is that contemporary individuals are rarely the offspring of the populations that inhabited the same regions thousands of years prior.”

However, ancient DNA does not exclude the possibility of cultural change occurring independently of intermingling. Carthaginians were historically linked with seafaring Phoenicians, yet ancient DNA indicates they share a closer affinity with the Greeks, whom they contended with economically.

“The significant shift in perspective from ancient DNA research is that contemporary individuals are rarely the offspring of the populations that inhabited the same regions thousands of years prior,” Reich remarked. “Human migrations have transpired across various time scales, frequently causing disruption to the communities involved, and these dynamics were elusive to predict without direct evidence.”

Another crucial insight provided by ancient DNA is the influence of evolutionary natural selection on human demographics.

Reich expressed that it was once thought natural selection had minimal impact on humans over the past 10,000 years, and his preliminary study from 2015 revealed only a handful of locations in the genome that had altered over the last 8,000 years in ways that might suggest natural selection.

Last year, a comparable study identified 21. Consequently, Reich and his team endeavored to devise techniques to diminish erroneous signals and enhance statistical robustness. In their analysis of 10,000 individuals’ genomes, they uncovered nearly 500 notable changes.

Reich currently posits that Europe, at the very least, is undergoing a phase of intensified selection that commenced 5,000 years ago, concentrating on immune and metabolic characteristics. Certain traits appear in the genetic record as increasing over time before sharply declining, such as genes associated with susceptibility to celiac disease and a severe variant of tuberculosis.

Reich stated that it remains unclear why these traits initially proliferated within the population, but it is probable they offered some unrecognized benefit before the associated health challenges overcame them.

“Narratives individuals tell about their heritage are almost invariably inaccurate,” Reich noted. “I do not perceive that as negative. I view it as a positive and humbling realization.”

More like this

“`